Using exercise to combat osteoporosis, the silent disease that affects 200 million people

Working out can help to prevent and mitigate the disorder, which leads to broken bones, reduced mobility and higher mortality

“I didn’t realize osteoporosis could be a problem until I broke my hip walking down the street,” Loles, 72, told me. “Everything was completely normal, then I crossed the road and caused a scene. All of a sudden, I was lying on the ground, couldn’t move one of my legs, and had a crowd of people standing around me.” She said she’s tired of seeing so many friends “end up breaking something pretty much as if by magic.”

A systemic disorder characterized by a deterioration in bone mass and microarchitecture, osteoporosis leaves people with weaker bones and a higher chance of suffering fractures. It’s a silent disease, because it often doesn’t cause any pain in and of itself. “I hadn’t felt anything really,” Loles said, when I asked her if she had noticed something wasn’t right before her fall. “Maybe just the odd twinge.”

According to the U.S. Endocrine Society, one in two postmenopausal women will have osteoporosis, and most of them will suffer a fracture. Broken bones lead to pain, reduced mobility and quality of life, and increased mortality. Bone mineral density — how strong our bones are — increases progressively throughout our youth, peaking at around 30. How high that peak is will be crucial to your bone density later in life, and comes down to both genetics and environmental factors, particularly exercise.

“I’ve been told I have osteoporosis and I’m worried,” Carola, 54, told me. “It seems like it’s something serious, but they haven’t properly explained to me what it’s all about.” The day I met her, she showed me the results of tests she had had. I looked over them, and gave her the following analogy: imagine a honeycomb and one of those mesh bags that your oranges come in at the store. They’re very different. The honeycomb is thick and firm; the mesh bag is flimsy, easy to pull apart. That’s what a bone with osteoporosis is like.

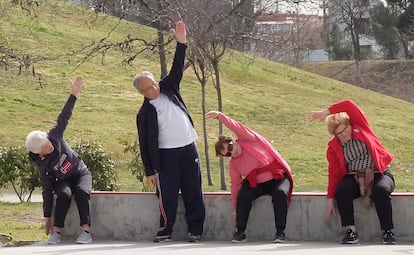

The disorder affects around 200 million people worldwide, and is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates; the International Osteoporosis Foundation describes it as one of the chief epidemics of the 21st century. But, as a study in the journal Sports Medicine explains, there’s a powerful weapon against it and it’s available to all: exercise. Physical activity can have positive effects on bone mass and help to prevent falls among older people, reducing the risk of fractures. “If I’d known before, I would’ve started getting some exercise,” Loles said. “But until I found myself lying on the ground with a broken hip, it didn’t even occur to me.”

Get checked out before working out

Before devising an exercise regime for someone with osteoporosis, it’s vital to carry out a risk assessment first. Loles suffers from the condition to a degree different than Carola. A bone mineral density test can provide an instant snapshot of the health of a person’s bones. Normally, it’s conducted using a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan. By measuring the mineral content of bones in specific areas, such as the hip and spine, the technique allows each individual’s level of risk to be graded.

“This score that I’ve got, -1.61 SD, what does that mean?” Carola asked. “Do I have to eat a lot of that yoghurt they advertise on TV? The doctor told me: look for somewhere to do strength training, but I’m still not totally clear on what I have to do.”

Generally, the results of a DEXA scan are compared with the bone mineral density of a healthy young adult, leading to what’s known as a T-score. The difference between a person’s bone mineral density and that of the healthy young adult, who would get a T-score of 0, is measured in units called standard deviations (the “SD” referred to in Carola’s results). The more standard deviations below 0, the lower the bone density and the higher the risk of fracture. According to the U.S.’s Osteoporosis and Related Bone Disease National Resource Center, a T-score between +1 and -1 is considered normal or healthy. A T-score between -1 and -2.5 points to low bone density, albeit not enough to be diagnosed with osteoporosis. A T-score of -2.5 or below indicates osteoporosis. The lower the negative number, the more serious the case. “We’ve seen the numbers — the doctor wants you to get some exercise,” I told Carola. “It’s time to start working out!”

Two women who have different levels of osteoporosis and are at different stages of their lives both asked me the same question: “Am I really going to start learning how to work out, at my age?” My response was: “Absolutely.”

“So… What do I do?” she exclaimed, looking flustered. “I can’t see myself lifting dumbbells!” The Sports Medicine study concludes that impact and resistance exercises can have a positive effect on bone density. Strength training is apparently the best option, but running, jumping and other high-impact aerobic activities can also improve bone density and muscle strength. The latter exercises should be avoided by people with a high probability of fracture, however.

No two people are the same — and that also goes for their training regimes. Before deciding the best exercises to do, each person’s situation should be thoroughly analyzed, by assessing what state of health they’re in and what co-morbidities they have (such as osteoarthritis, neuromuscular weakness and cardiopulmonary conditions). This will ensure that the exercise, supervised by a qualified professional, will be carried out in the right doses, and is both safe and effective.

Neither fragile nor dependent

By leading to bone fractures, osteoporosis can have the knock-on effect of fostering dependence. If we want to be self-sufficient, independent women, we need to train up our strength. As we get older, the goal is to avoid fractures limiting our ability to go shopping, to work, out for a walk… “I have friends who need to use a walker,” Loles said. “Either that, or they’ll put bottles of water in their shopping cart and use that instead, so people don’t realize. They push it around to help them stay on their feet, because they struggle otherwise… I refuse to do that! I want to go about my life all by myself.”

Experts agree that strength training can reduce bone loss. A study published by Osteoporosis International has monitored its effects on bone mineral density in postmenopausal woman, and has reached the following conclusions:

- It’s best to do ‘free weight’ training (barbells, dumbbells, kettlebells).

- Do two sessions a week.

- Train at an intensity that challenges your body (weights should be difficult to lift).

According to Exercise and Sports Science Australia, these are the levels of exercise that should be prescribed, depending on an individual’s degree of risk:

Low risk

People who are asymptomatic (T-score between +1 and -1) and do not present risk factors. Improving strength and functional capacity is recommended. This involves doing high-intensity impact exercises and progressive strength training.

Medium risk

Low bone density (T-score between -1 and -2.5) and some risk factors. In this case, moderate-impact exercise is recommended, along with strength training and activities designed to improve balance and posture.

High risk

People who may present several risk factors (T-score of -2.5 and below). Training could be focused on posture correction and reducing the risk of falls. Exercises should only involve moderate resistance. Movements that could increase the risk of falling should be avoided.

Loles and Carola are women who have different levels of osteoporosis and are at different stages of their lives — but, curiously, both asked me the same question: “Am I really going to start learning how to work out, at my age?” My response was: “Absolutely: get yourself some exercise.”

Before starting

FIND OUT HOW HEALTHY YOUR BONES ARE: Take a recognized test, carried out by specialist professionals, to ascertain what your bone mineral density is. Make sure to take into account any possible associated pathologies.

GET A PRESCRIPTION FROM AN EXPERT: Go and see a fitness professional.

DO WHAT’S BEST FOR YOU: No two people are the same, nor are their training regimes or levels of osteoporosis. Exercise should adapt to the person, not the other way around. This will ensure your training is effective, sustainable and safe.

WATCH YOUR TECHNIQUE: You can start exercising at any age. Remember: the first thing to do is learn how to move. You should have a good technical command of the exercises you do; then you can start stepping up the intensity.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.