The most promising drug against Alzheimer’s shrinks patients’ brains

A new study on lecanemab and other similar drugs reveals a volume reduction of unknown consequences that experts are divided about

The most promising drug against Alzheimer’s in recent decades reduces patients’ brain volume without scientists knowing why or what effects it may have in the long term. The drug, called lecanemab, reduces cognitive impairment associated with this disease by 27% in patients who are in the early stages of Alzheimer’s. But the experimental drug also produces worrisome side effects such as minor bleeding, and may have been linked to the deaths of two people.

A new study has analyzed another side effect of this drug and others like it: the accelerated brain volume loss in patients who take it. According to the analysis, people who receive lecanemab experience a 28% greater reduction in the size of their brains than those who take a placebo. Another similar experimental drug, donanemab, also produces similar effects.

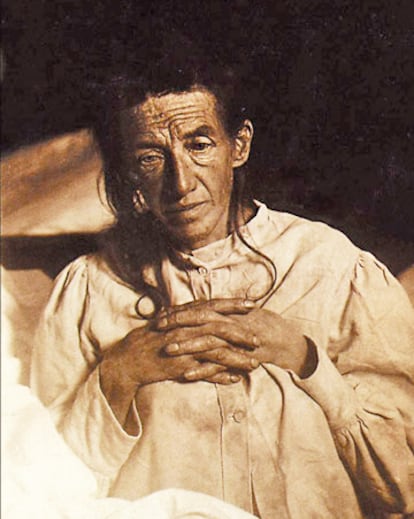

In 1901, a woman with paranoia, insomnia, sudden mood swings and memory loss was examined by the German neurologist Alois Alzheimer. The woman’s name was Auguste Deter. The German doctor’s notes on his dialogues with her portray the ravages of this disease: “She sits on the bed with a helpless expression. What is your name? Auguste. Last name? Auguste. What’s your husband’s name? Auguste. [...] You are married? Yes, with Auguste.” There was little the doctor could do for his patient, who died five years later. Alzheimer analyzed the woman’s brain and described the characteristic lesions of the disease.

More than a century later, Alzheimer’s disease affects more than 30 million people worldwide and there is still no cure. The expectations surrounding lecanemab are huge because it could be the first drug that stops the mental deterioration process associated with this disease. But its effects are so timid that many experts believe that they are imperceptible to patients, their caregivers and their families.

Although the cause of the disease is unknown, it has been documented that Alzheimer’s kills neurons and that the brain of patients shrinks progressively. That is why it is so surprising that a drug that theoretically stops the disease produces even more brain volume loss than the disease itself.

Scott Ayton, a neurologist at the University of Melbourne (Australia) is the main author of the new study, which was published in the specialized journal Neurology. The analysis reviews the results of 31 clinical trials of drugs aimed at eliminating amyloid-beta protein, one of the markers of the disease. “Our results are worrying. We do not know what consequences the observed reduction in brain volume may have, so we are calling for more studies,” he warns. “The pharmaceutical companies that funded these clinical trials have a wealth of data that can shed light on this problem of brain atrophy, but that data has hardly been analyzed and the companies have not published it.”

Ayton was an advisor to Eisai, the Japanese company that developed lecanemab together with the US firm Biogen. He says he alerted the company to these results and asked for detailed data on brain volume, but they didn’t give it to him.

The available data are based on a clinical trial with more than 1,700 early-stage patients in 14 countries who were followed for 18 months. But several experts consulted by this newspaper warned that follow-up data over the course of three or four years will probably be necessary to determine whether the observed benefits are sustained or stagnate. It is also important to resolve all the unknowns that the new drug raises.

Two years ago, the FDA approved another drug against Alzheimer’s, aducanumab, despite the fact that it had not shown effectiveness. Three experts on the official review panel resigned in protest. Aducanumab has been a medical and economic fiasco for Biogen, the company that developed it and is now also promoting lecanemab together with the Japanese company Eisai.

An Eisai spokesperson told EL PAÍS that they are continuing with the approval process and suggests that the observed effects may be due to the disappearance of the amyloid protein from the brain. The pharmaceutical company did not answer the question of whether it will publish the complete data sets on the drug so that independent scientists and doctors can analyze them.

In an editorial accompanying Ayton’s article, neurologists Frederik Barkhof and David Knopman—one of the experts who resigned over the aducanumab scandal—highlighted the uncertainty about the effects of the “enigmatic” loss of brain volume. It is possible, they wrote, that it does not have an impact on patients’ health, although they ruled out that it is only due to the disappearance of the amyloid protein plaques.

Ayton’s work also found ventricular enlargement in patients’ brains, and observed “a striking correlation” between ventricular volume and the frequency of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities. The researchers expressed concern that brain volume and ventricular volume appear to move in opposite directions from what would be expected with a therapeutic intervention. The only way to find out for sure, they said, is to continue observing the patients who took these drugs.

Neurologists are divided between those who clearly hear alarm bells and those who believe that the reduction of brain volume may be an unimportant side effect. Currently it is impossible to know who is right.

Raquel Sánchez del Valle, coordinator of behavior and dementia at the Spanish Society of Neurology, believes that these recent observations “should not stop the approval” of lecanemab, since they do not question the “safety” of the drug. The neurologist highlights that the reduction in brain volume may be an indication that the drug is working. Similar brain shrinkage, she explains, occurs with multiple sclerosis drugs that have proven to be effective.

Sánchez del Valle, a neurologist at Hospital Clínico in Barcelona, has participated in clinical trials of lecanemab, but explains that she cannot say if any of her patients have suffered a reduction in the size of their brains because she does not have access to that information. “That is in possession of the pharmaceutical companies” that finance the trials, something that is common in clinical trials, she details. It’s the same problem Ayton ran into in Australia.

David Pérez, head of neurology at Hospital 12 de Octubre in Madrid, explains that “the loss of brain volume with this type of drug has been known about for a long time, but on many occasions it has been tiptoed around because the drugs did not prove their efficacy and were dropped. It is logical to think that the observed brain atrophy is due to the loss of neurons. It can be argued that it is due to removal of the pathological amyloid protein, but this is at least debatable. The most important thing is to determine if after five or six years of treatment with lecanemab, its positive effects continue, which would represent a striking therapeutic effect, or if they stagnate, as has happened with previous drugs.” In his opinion, “full approval of this drug would be premature.”

Miguel Medina, deputy scientific director of the Network Center for Biomedical Research in Neurodegenerative Diseases CIBERNED, believes that “asserting that the loss of brain volume is due to the elimination of amyloid plaques and that it does not cause damage is pure speculation.” This expert believes that the matter is “significant enough to be taken seriously and monitored.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.