Are psychedelic drugs beneficial for people without mental disorders?

Hallucinogenic substances are experiencing a renaissance after very promising scientific research results

Ayahuasca is a psychoactive drink that has been used for centuries as a spiritual medicine by the indigenous peoples of the Amazon region. An archaeological discovery in southern Bolivia identified the two main ingredients of ayahuasca on utensils buried in a 1,000-year-old tomb: harmine, an alkaloid found in the banesteriopsis caapi vine, and DMT, a hallucinogen extracted from the psychotria viridis shrub. Archaeological sites such as this one, where coca residue was also found, are evidence of a body of knowledge that challenges contemporary assumptions about the primitivity of ancient peoples. These South American indigenous peoples were able to identify substances with psychoactive effects among the tens of thousands of plants in their environment, and they traveled long distances to collect them. They also learned how to combine and use them in rituals to relate to divine forces, connect with the natural world, and understand their own place in creation. And there is much older evidence of the use of psychedelic substances around the world.

Western mistrust of these vision-inducing drugs is deep-rooted. A 1638 directive from the Spanish Holy Office, quoted by Antonio Escohotado in his exhaustive 1983 book General History of Drugs, forbids the use of peyote by Spanish subjects in America, calling it a source of “superstition opposed to the purity and integrity of the Catholic faith.” In the 20th century, Western scientists synthesized new hallucinogens such as LSD and recognized the therapeutic potential of the controlled use of MDMA and psilocybin found in certain mushrooms. But then, US President Richard Nixon’s war on drugs made scientific research on hallucinogens virtually impossible by banning their use.

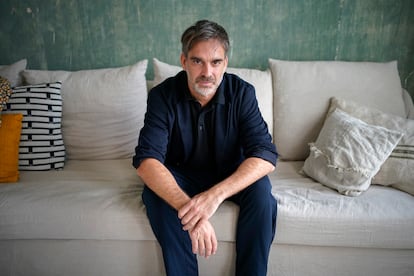

After decades of neglect, scientific research on these drugs is experiencing a renaissance. Clinical trials of MDMA have demonstrated its potential as a therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and a form of ketamine has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat depression. Psilocybin therapy also shows greater antidepressant potential than other traditional drugs. To understand some of the latest advances in this field, EL PAÍS interviewed David Erritzoe, a Danish expert on psychedelic drugs at Imperial College London, who was recently in Madrid to give a talk about the therapeutic potential of psychedelics.

Question. We tend to generalize when we talk about psychedelics such as ketamine, MDMA, DMT in ayahuasca, and psilocybin in mushrooms, but they seem to have different effects.

Answer. They have many things in common. Psilocybin, DMT and mescaline extracted from cacti have very similar effects. They are different from what we would call atypical psychedelics, like MDMA. And then you have ketamine, which acts on a completely different physiological system, and its effect is mediated through a different part of the brain. But all of these drugs produce some kind of altered state of consciousness. These substances are analogous to different doors in the same house. Their effects vary in duration, which may influence how they are used in therapy. MDMA, for example, produces a more pleasant experience, which can be helpful when a patient is interacting with a therapist. A patient may not be able to do that when experiencing the peak effects of some of the other drugs.

Q. How could these substances be used to treat mental health problems? Must they always be administered by a therapist, or could they be self-administered at home like some other antidepressants?

A. Psilocybin, which is one of the drugs that is furthest along in the drug development process, is for people who don’t respond to conventional treatments for depression. It’s not a drug that a family doctor would prescribe for you to take at home, nor would it be used frequently. It would be used in a clinical context with specialists who would first do some psychological preparation with the patient. The specialist would accompany the patient through the experience and do psychological integration work afterwards. Then there is ketamine, which comes from the world of anesthesiology and has been used in medicine for decades. It’s quite safe and doctors are comfortable with it, so it has been used with lower levels of supportive psychology. We think that psychological support makes ketamine safer and even increases the effects, but we don’t yet know for sure. We do know that the drug itself has therapeutic effects.

With classic psychedelics, I think it’s important to have therapeutic support during the experience, because they can evoke subconscious, traumatic, relational, and troubling thoughts. It’s important not to leave a patient alone in that situation.

Q. The most common psychiatric drugs usually have the effect of improving a depressed person’s mood, or calming someone who is anxious or upset. These types of changes seem easier to measure than the benefits of the altered state of mind that psychedelics produce. What effects do you measure with psychedelics?

A. People who have taken these drugs often say they experienced a psychological revelation, or that they discovered the inherent meaning of past life experiences. There are questionnaires that can be used to assess the results. But I think that the reason these drug-induced experiences are so therapeutic is because, whether you’re suffering from addiction or depression, you’re stuck in that state. You’re stuck in harmful thought patterns and habits. You’ve lost your ability to connect with the world and the people around you, and these drugs allow you to reconnect with the universe, nature, people and with your own emotional life. These drugs can set you free from these traps, and those therapeutic effects often last long after the drug is gone from the brain. This is not to say that the experience is easy for everyone, which is why it’s important that they be administered in a safe environment.

“Can new psychedelic drugs become big business? Absolutely”David Erritzoe, expert on psychedelic drugs at Imperial College London

Q. The cultures that have used these psychedelic substances for millennia are very different from ours, which is much more individualistic and less connected to nature. Do these cultural differences influence the effects of these psychedelic drugs?

A. Yes, in some cultures, a relationship with nature is integrated into their belief system and they live in close contact with it. This doesn’t happen in our societies and big cities, and we are much more individualistic. But we’re still social beings. We need to exist in a social context, and we need a connection with nature and with other people. Even when administered in a clinical, Western context, the patients almost always say they felt a connection with nature – it’s fascinating. I think there is something about these experiences that transcends those cultural and historical differences.

Q. With a few exceptions like caffeine, our society approves of using drugs when you’re sick, but not to feel better when you’re well, nor to learn more about yourself or connect with nature and other people.

A. Some people are already doing things like traveling to South America or going on nature retreats to take these drugs and work on themselves. While mental health is the main focus of Western clinical development of these compounds, it’s very likely that psychedelic drugs are also beneficial for people without mental disorders. However, this is not the main focus of our work, which is to see if they have therapeutic potential. We have to test these drugs within our current system and fulfill all the clinical trial stages until we can prove that they are effective and safe. Our priority is those who are suffering, although some people will continue to use these drugs in other settings, as always. There is also potential for some of these drugs to be used as a kind of vaccine to develop resistance to mental problems, but that’s not a priority right now.

Q. What’s your view of those who travel to South America to have psychedelic experiences with shamans?

A. As a psychiatrist, it’s easy to say that people should only use these drugs in a clinical context with a specific therapeutic format. But I think that would be arrogant, because there is a shamanistic culture with wonderful, wise people who have many generations of experience using and sharing these compounds and experiences. I think there are always risks, and you could end up in an unsafe retreat or place. But for most people, I wouldn’t venture to say whether it’s safe or not. As long as the shaman or therapist knows what they are doing and there is an adequate preparation phase, it can be a safe experience anywhere in the world. Obviously, if you are taking a lot of medication or have a family history of psychosis, these types of experiences are not recommended. We have learned a lot from these cultures, and they also take precautions when using these drugs.

“You’ve lost your ability to connect with the world and the people around you, and these drugs allow you to reconnect with the universe, nature, people and with your own emotional life”

Q. This renewed interest in psychedelics is attracting a lot of attention from businesses and investors. How could this affect the development of these drugs? For example, Janssen Pharmaceuticals developed esketamine, which is basically ketamine, but it costs a lot more and is patent protected.

A. The business world has taken note of the promising work of some underground communities and academic centers like our own laboratory. Obviously, the pharmaceutical world wouldn’t be interested if we didn’t have such promising results.

To attract investors, you need a business model. That’s what Janssen did – they developed the part of ketamine that binds best to the most important target in the brain. This approach was used to develop other antidepressants like escitalopram. The pharma companies develop a safer and more efficient molecule, and then obtain a long-duration patent. This is the business model for developing a better version of the drug – it’s the Western pharmaceutical tradition.

Can [new psychedelic drugs] become big business? Absolutely. Is that a problem? I’ll be impartial – I think it’s positive in that it will enable us to provide the drugs to more patients by having them formally approved through the regulated drug development process. That’s a huge effort and costs a fortune. The sad part is that compounds like psilocybin already exist in nature, so why not use them? But that’s not the system we have built in the Western world.

I have mixed feelings about this. On one hand, we can develop some very well-tested and safe products with exact dosage information, which is medically valuable. But it’s strange to have all these companies making adjustments to molecules that already exist, even though there’s a lot of learning going on with the science associated with the drug development process. There is also some concern that businesses will prioritize profitability by making everything faster, simpler and more efficient, and will neglect the expensive psychological support that should be provided along with the medication. That can be risky.

“The experience is not easy for everyone, which is why it’s important that they be administered in a safe environment”

Q. Do you think that people should be allowed to use these psychedelics outside the pharmaceutical-medical system? Or that current restrictions on their use should be relaxed?

A. That’s a tough question, but in general I think it’s strange to punish someone for using any substance. The Portuguese model of decriminalization seems to have worked very well. From a psychological perspective, psychedelics can be very tricky and also very scary for some people. They can even be traumatic for a very young person who takes them in an inappropriate setting. So it’s hard to declare that these drugs are completely safe and should be fully legalized. The people who are taking these substances now tend to be well-informed and smart about it. But if all restrictions were lifted, some people would take them recklessly. I would point people to the Portuguese decriminalization model and ask them to think about whether the war on drugs has worked.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.