Could recreational drug ketamine provide the antidote to depression?

Neuroscientist Hailan Hu says the mental illness remains taboo in parts of the world, but should be treated just like diseases that affect other parts of the body

Ketamine was first employed in the 1960s as an anesthetic in operating rooms and on battlefields, as well as being a recreational drug favored by the counter-culture. However, as professor Hailan Hu, executive director of the Center for Neuroscience at Zhejiang University’s Faculty of Medicine, explains: “About 20 years ago, a team of scientists in the United States accidentally discovered that, administered in very low doses, it can rapidly improve the mood of patients suffering from depression.”

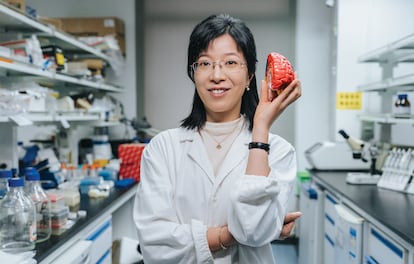

Professor Hu, 48, and laureate of the 2022 L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science International Awards - Asia and the Pacific, has been leading investigations into the effects of ketamine in an area of the brain called the lateral habenula: “It is a very small part of the brain, but it plays a fundamental role in negative emotions such as stress, fear or disappointment,” she says. Researchers commonly refer to this area as the “anti-reward center,” because it blocks the “reward” areas of the brain that release dopamine and serotonin - neurotransmitters associated with pleasure.

When a person is suffering from depression, “the habenula becomes overly active, which suppresses reward and causes moodiness or depressive states,” Hu explains. And that’s where ketamine comes in: as the drug “directly affects activity in that region of the brain.” If ketamine has one remarkable property, according to Hu, it is its ability to swiftly reduce the symptoms of depression in comparison to conventional antidepressants. “Compared to the six to eight weeks that traditional drugs can take to improve a patient’s mood, ketamine can start to take effect within just one hour.”

Several clinical trials with ketamine have been conducted over the past two decades and some regulatory agencies, such as the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency, have given the green light to esketamine, an antidepressant derived from ketamine and administered in the form of a nasal spray.

Ketamine, though, is not without its drawbacks. As Hu points out, the drug comes with side effects. In addition to potential bladder problems, ketamine is notoriously addictive: “Therefore, the doses used to treat depression are very low,” the neuroscientist says. A 2018 review published in The Lancet Psychiatry noted that further large-scale clinical trials are needed to assess the long-term safety of using ketamine to treat depression. By studying the effects of the drug on the brain, Hu hopes to better understand how depression also affects this vital organ: “Perhaps then we can find other drugs and new compounds that have the same rapid antidepressant properties, but with fewer side effects.”

Hu describes the human brain as “possibly the most complex system in the universe.” Hundreds of scientists have dedicated themselves to attempting to unravel the mechanisms of depression. “There is a popular hypothesis, according to which this disease is caused by an imbalance of chemicals in the brain, or due to a lack of dopamine or serotonin,” she says. The majority of traditional antidepressants, Hu adds, have been designed on the basis of this hypothesis and work primarily to increase the level of these substances in the brain. However, as Hu points out, “the fact that these drugs work so slowly suggests that this is probably not a direct mechanism, but rather that they are acting indirectly.”

The impact of Covid-19 on mental health

According to the World Health Organization, 5% of the world’s adult population suffers from depression and several investigations have been undertaken to analyze the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on mental health. A meta-analysis published in the scientific journal Psychiatry Research concluded that the prevalence of symptoms of depression in populations affected by Covid-19 is over three times higher (15.97%) than among the overall population (4.4%). “Uncontrollable stress is a very important factor that can induce this disease,” notes Hu. During the pandemic, millions of people around the world were forced to confront situations beyond their control, such as confinement and severe financial problems.

However, depression does not affect everyone in the same way. “This is what we refer to as resilience. People can be subjected to similar amounts of stress, but some are more resistant while others are more vulnerable,” says Hu. In addition to a possible genetic predisposition, the scientist points out that previous experience can also have an impact: “If you experienced some kind of challenge or a mild form of stress early on in your life, that can help you to develop a certain resilience against depression.”

Hu’s advice to ward off the specter of depression is reasonably straightforward: exercise, meditation and plenty of sunlight. “Exposure to the sun can reduce the likelihood of the anti-reward center becoming overactive, in the same way that ketamine does,” she says. Hu also prescribes lowering expectations in day-to-day life as a way of managing stress: “If they are too high and can’t be achieved, it can provide a trigger for negative moods.”

However, as Hu notes, in some parts of the world depression is still a taboo subject and therefore underdiagnosed. While the investigator believes more education is required, she says that progress has been made in recent years. “Previously, people thought depression was a psychological problem that you had to overcome on your own. But more and more people are now realizing that it is a disease of the brain and must be treated in the same way as diseases that affect other parts of the body.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.