Therapy with MDMA? Experts debate the use of psychedelic drugs in medical treatment

Research centers and companies are investigating the potential mental health benefits of hallucinogenic substances, decades after they were declared illegal

Let’s start with a definition. What are we talking about when we talk about psychedelics? The word “psychedelic” comes from the Greek for “manifesting the mind.” We might say that psychedelic substances contain molecules, natural or synthetic, that allow access to other states of consciousness. “The premise of psychedelic research is that this special group of molecules can give us access to other modes of consciousness that might offer us specific benefits, whether therapeutic, spiritual, or creative,” writes the author Michael Pollan in his 2018 bestseller How to Change Your Mind. Pollan’s book has helped revive the debate about therapeutic uses for substances like LSD and psilocybin.

It seems government officials have also begun to change their attitudes about these molecules. On January 5, Canadian health authorities modified food and drug regulations to allow doctors to request the use of substances including psilocybin, MDMA and LSD to treat certain patients. States including Oregon have loosened their laws around the substances. And this year the California state senate is set to discuss Bill 519, which proposes the decriminalization of certain hallucinogens.

“Hallucinogens have had a torturous path since LSD was synthesized by Albert Hofmann in 1938,” says Sergio Oliveros, a Madrid psychiatrist specializing in psychotherapy and the psychology of the self. “Between 1950 and 1967 its effects on depression, anxiety and addictions were studied. But then it was declared illegal.”

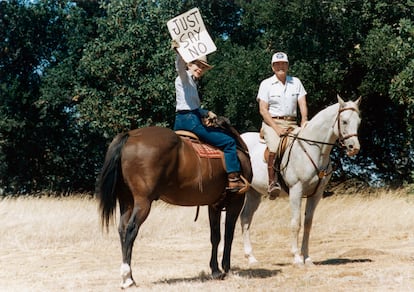

The persecution of psychedelics started in 1971, when the United States included LSD as a Schedule 1 drug, labeling it as highly dangerous. It gave a forceful argument: “It has a high potential for abuse and it has no medical purpose.” Neither of those statements are completely true, but as a result, nearly all the countries in the world followed the example and made LSD illegal. “The United States is always a pioneer of illegalization,” explains Francisco Azorín, a lawyer who specializes in drug legislation and has written several books on the topic. “In this case, it was the state of California when Ronald Reagan was governor [1967-1975]. Then it went to federal legislation, and then it was included in a United Nations convention.”

In 1985 MDMA, known as ecstasy and usually associated with wild raves, was declared illegal. It’s not strictly a psychedelic, but it had been used to successfully treat depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and addictions. Ketamine, a powerful anesthetic with dissociative effects, has also been used to treat those conditions. Its limited use in medical treatment is currently permitted. The European Medicines Agency has approved a depression medication made with esketamine, which is essentially a version of ketamine that was modified so it could be patented. The pharmaceutical Janssen sells it under the name Spravato, and it is administered as a nasal spray.

Specialists argue that illegalization of hallucinogenic substances was premature and based more on political criteria than medical evidence. LSD was considered the fuel of 1960s counterculture, and the conservative American political establishment feared what it could bring. The panic was so great that then-president Richard Nixon called Timothy Leary, a Harvard professor who became an evangelist of LSD, “the most dangerous man in America.” Once psychedelics were prohibited, medical research on their uses became almost impossible. The substances, created in labs and studied as possible pharmaceuticals before making their way into the streets, came to be considered lethal recreational drugs.

But that stigma has started to change. Netflix is full of documentaries about “magic mushrooms” and other psychedelic substances, some featuring mainstream stars like Gwyneth Paltrow. The substances also appear in fictional TV shows, including HBO’s Nine Perfect Strangers, which stars Nicole Kidman, and on albums like British musician Jon Hopkins’ Music for Psychedelic Therapy. The world’s most important newspapers and magazines have begun discussing the merits of these substances. Just three weeks ago, The New York Times published an article about the successful use of MDMA in couples therapy, titled “Can MDMA Save a Marriage?” Institutions like Imperial College London and Johns Hopkins University are conducting clinical studies using psychedelics to cure afflictions including severe depression and PTSD.

In May 2021, the publication Nature Medicine published the results of the most advanced psychedelic therapy test to date. It examined the effects of MDMA on patients with PTSD. Science magazine included the study among its nine scientific breakthroughs of 2021: “After two months, 67% of those who got MDMA no longer met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD.”

After decades of criminalization, psychedelics have taken the stage again. “There has been a lot of research in the last 20 years, mostly by independent scientists. They have made a lot of progress in pharmaceutical and neurobiological knowledge. But, above all, this emerges in a moment of crisis for classic psychopharmacology,” explains José Carlos Bouso, scientific director of Iceers (International Center for Ethnobotanical Education, Research and Service), a Barcelona-based institution dedicated to studying psychoactive plants. “We’ve started to see that the psychiatric medications that we have were discovered 50 years ago, and no new molecules have appeared. The side effects of those medications are considerable. Many pharmaceutical companies are no longer investing in psychiatric medication because it’s a dead end. That creates a need for new treatments, and that’s where psychedelics come in,” he says.

Researchers have begun attempting to create medications based on psychedelic substances. Academic labs and companies are exploring their potential, and some see a significant business opportunity. On January 20, Eleusis, an American company that develops psychedelic medications, announced that it will go public after joining investment fund Silver Spike. And a petition to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to authorize MDMA in medical treatments is in process. “Everything indicates that the FDA will legalize MDMA in 2023 for the treatment of post-traumatic stress,” confirms the lawyer Francisco Azorín.

It seems like public opinion is also in favor. “There’s a lot of scientific and social approval, to a point that we’re at risk of overstating it, because there’s an optimism that’s not evidence-based,” explains Bouso. “We have to wait for the clinical trial results to come out. What has been published are preliminary results of pilot tests with just a few patients. What’s surprising is how just a few studies got enough attention from pharmaceutical companies that they’re investing in developing psychedelic medications.”

In How to Change Your Mind, Michael Pollan places the beginning of “the modern renaissance of psychedelic research” in 2006, a year of three landmark events. The first was the 100th birthday of Albert Hofmann, the Swiss doctor who was the first to synthesize LSD and psilocybin. Hofmann was still alive and he celebrated his birthday with a party in Geneva, which turned into a conference where researchers from the United States and Switzerland, then at the vanguard of government-approved psychedelic research, debated their findings. The second milestone was a case that reached the US Supreme Court, which ruled that a small religious group, the local branch of the Brazil-based sect União do Vegetal, could legally import ayahuasca for sacramental usage. The decision opened up the possibility of drug legalization for religious purposes in the United States. The third event was the publication of an article titled “Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences” in the Journal of Psychopharmacology. According to Pollan, it was the first double-blind and placebo-controlled clinical study in over four decades to examine the psychological effects of a psychedelic.

Pollan argues that those three events unleashed the research that had been on hold. But Bouso disputes the author’s narrative, though. “That’s the Anglo story, basically the American, story, which forgets the European school that had been studying it for many years,” he says, speaking from his own experience as a pioneer in MDMA research for the last 20 years. In 2002 Bouso conducted a clinical study, approved by Spain’s Ministry of Health and funded by the United States, which studied the drug’s effects on trauma caused by rape. “At that time, the general attitude about these treatments was totally different. When the media started talking about my study, it got shut down in two days,” he remembers.

Bouso remains skeptical about the future of psychedelic therapies. “In my opinion, mental problems aren’t just the fruit of a mental disturbance, but also of social and economic conditions. This search for a magic bullet that solves the problem seems reductionist to me.” But de-stigmatizing the use of such substances is important. “Many of the most notorious perils are either exaggerated or mythical,” Pollan writes. “It is virtually impossible to die from an overdose of LSD or psilocybin, for example, and neither drug is addictive.” Specialists, and some politicians, point out that their criminalization also follows the classist logic of the war on drugs. But it’s also clear that psychedelics won’t be a perfect chemical remedy for the mental illnesses that have plagued the world since the Covid-19 pandemic began. They may be useful, but it remains to be seen whether they’re the cure-all that many defend.

In any case, why do they work on afflictions that are resistant to traditional pharmaceuticals? The documentary Magic Medicine, available on Netflix, recounts a four-year study of psilocybin treatment for depression. Robin Carhart-Harris, an English psychologist and neuroscientist who has directed Imperial College London’s Centre for Psychedelic Research since 2019, explains that “it seems like psilocybin produces a reset of the base of the cerebral cortex, a part involved in depression, and then establishes healthier functions.” Bouso is more specific. “There are two explanations about why psychedelic treatments can be useful, and they complement each other. One is more neurobiological: they produce a series of mechanisms that somehow can modulate neural pathways, and that translates into the patient’s recovery.” In that theory, the substance acts as a key and the neuron as a lock. “And then there’s the explanation that they’re substances that produce an intense altered state of consciousness, in which people can access content about their lives, their relationships and their most intimate nature. With all that, they can go to therapy and discuss their revelations in the session. Either way, the interesting thing is that it combines psychotherapy with pharmacotherapy, and clinical trials have been fairly positive. Many patients seem to leave those altered states of consciousness feeling liberated,” says Bouso.

Though hallucinations have become associated with horror in the collective imagination, they could have healing qualities. “All these altered states of consciousness imply hallucinations, but we have to reclaim that term, because it’s very stigmatized. Hallucination is defined as ‘perception without an object,” says Bouso. “And that can be any product of human thought, including the imagination. Many things produce hallucinations. Dreams are hallucinations, and in an epistemological sense, everyday life is a hallucination because photons don’t have light, sound waves don’t have sound and particles don’t have colors. It can seem like a fine line, but it is what it is.”

The Spanish scientist says that the concept of hallucination forms part of the daily life of a very high percentage of the population, in some cases up to 40%, who do not have any kind of mental pathology. “Whether a perception without an object causes fear or becomes a source of knowledge is different,” he says. “In the popular imagination, that idea has been associated with mental illness. These pharmaceuticals induce hallucinations but they don’t cause mental illness.”

It’s important to note that psychedelic therapies do not use illegal substances bought clandestinely on the street, but medications made to be taken under supervision, although they’re not on the market yet. “Before a pharmaceutical goes on the market, it goes through four phases of clinical tests that reduce its toxicity as much as possible and define its mechanism of action and its uses,” explains Oliveros. “It’s possible that we’ll have pharmaceuticals with these effects in five years, probably in 10, certainly in 15. For now, their use is purely anecdotal because of the lack of adequate experimental data.”

When that happens, we’ll be in the hands of doctors. “The medical community has a similar distribution of personalities as the general population,” notes Oliveros. “When they’re available, there will be people motivated by profit who push for their mass usage without evaluating risks, others who will only use them when the majority does and yet others who never will because of their own beliefs or prejudices.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.