Fake Covid passports and PCR tests: The scams behind the lucrative business

The price of these fraudulent documents has shot up over the past year, but paying a hefty fee is no protection against being cheated

Andrea got a job as a dancer abroad last October. She had not been fully vaccinated, she says, because she had just had the virus. That information was enough to board the plane at Barcelona’s El Prat Airport, but not for entry to her destination, where a Covid vaccination certificate was required. Andrea – not her real name – decided to acquire the document on the black market and contacted numbers advertised on Instagram. After paying out €800 via Bizum and passing on her personal data, she realized her mistake. “They sent me a photoshopped document with a QR code that showed the name Gabriel when I passed a scanner,” she tells EL PAÍS. Ashamed of seeming naive, she did not report the scam to the police. How could she when what she wanted to buy was illegal?

Cybercriminals have pounced on the opportunities thrown up by the coronavirus pandemic. In Andrea’s case, they were taking advantage of those seeking a so-called Covid passport. This black market exists, and the prices being quoted are not low. A recent study by the Israeli multinational cybersecurity company, Check Point Research, has detected a steep increase in fees. While in October the average price paid for a fake passport was around $250 (€220) and $25 (€22) for a negative PCR test, by January it had risen to around $600 (€530) and $100 (€88), respectively.

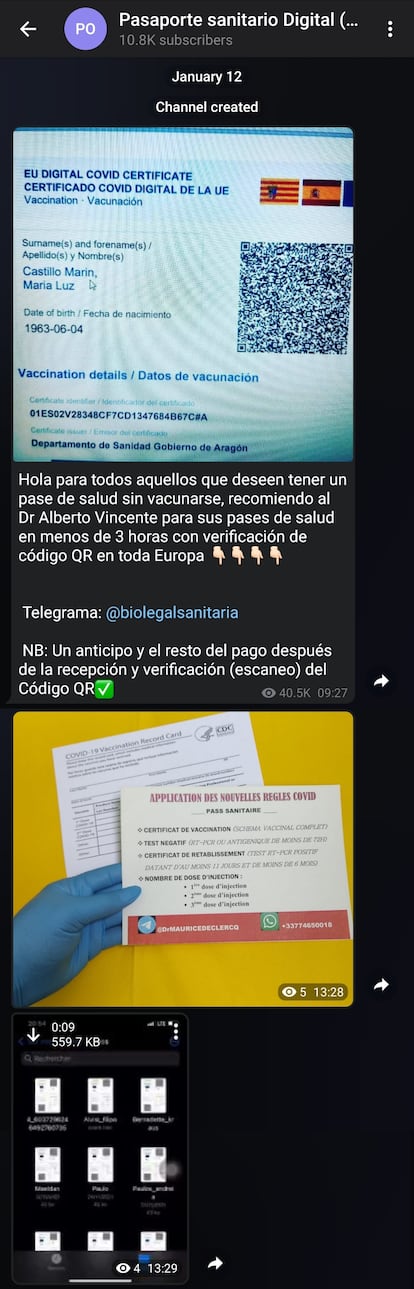

The sale of fraudulent vaccination certificates began to attract the attention of the authorities before last summer, when the European Union launched the Digital COVID Certificate. This is a document that can be carried on cellphones in the form of a QR code, allowing citizens to prove that they have either been vaccinated, have recently had the virus and therefore have some immunity or that they have tested negative in a PCR or lateral flow test.

Counterfeit certificates are mainly distributed via Telegram or via the dark web and the favored method of payment is cryptocurrencies, especially bitcoin. “Digital currencies have a very desirable feature for these types of criminals: you can’t reverse the transaction,” says Eusebio Nieva, technical director of Check Point Software for Spain and Portugal. “Once it has been made, it is recorded forever in the blockchain ledger. You can’t go to the bank and ask them to stop the payment. They are also difficult to trace, although not impossible: you always know which card or virtual wallet the bitcoin has come from and where it has gone.”

You don’t have to be a computer whiz to acquire one of these counterfeit products. In the bona fide ads on the Telegram channels, detailed instructions are provided on how to buy the bitcoins (or whatever cryptocurrency is required) and how to make the transfer.

Of course, there is no guarantee that the purveyors will actually come up with the goods. “You can get drugs, weapons, human organs and also certificates and high quality forged official documents on the dark web,” says Deepak Daswani, a hacker and cybersecurity consultant. “But this is like everything else: the first ads you come across – the ones that are easiest to see – will be scams. Accessing these kinds of services is not that easy; it often involves an invitation; for someone you trust to give you the necessary links.” Naturally, if criminal activities were easily available, they would also be easily shut down.

Booming business

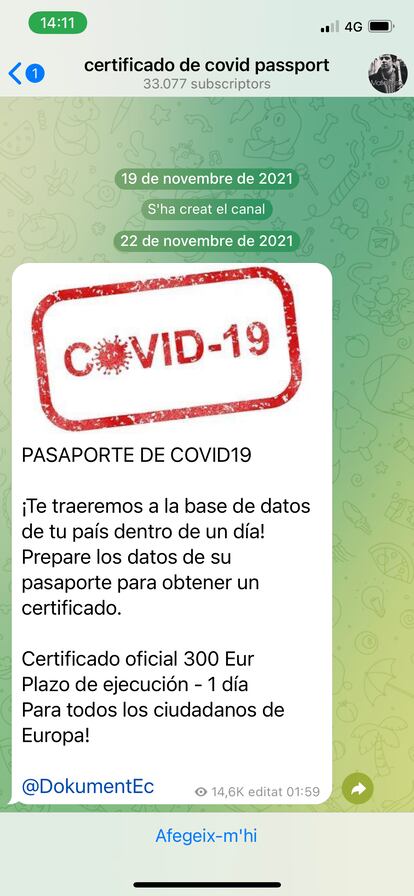

The number of scams is multiplying as are the number of victims like Andrea. At the time of going to press, there was at least one group on Telegram in Spain with more than 33,000 subscribers that appeared to be a scam. The ad, active since November, promises a so-called Covid passport in a day in exchange for €300 and the buyer’s personal details.

Spain’s National Cybersecurity Institute (Incibe) warned as early as September last year that they were detecting a proliferation of scams related to the sale of fake documents. “We want to stress that seeking to buy a Covid certificate is illegal,” says Ángela García Valdés, Incibe’s citizen cybersecurity expert. “But, also, that by committing this illegal act, people may be subject to fraud in as much as the certificates might never be sent and they lose their money; or if they pay with their credit card, their data may be stolen and they will find themselves making unauthorized payments.”

“Vendors are choosing to advertise and do business on Telegram because it increases their distribution,” says Oded Vanunu, head of product vulnerability research at Check Point Software. “This social network is less technical compared to the dark web and can reach an inordinate amount of people very quickly.” Some ads analyzed by the company target anti-vaxxers. One of the advertisements found by the analysts explicitly stated: “We are here to save the world from this poisonous vaccine.”

Vaccination certificates were launched in July 2021. A few months earlier, between March and May, some analysts, such as those at Check Point Research, detected a 500% increase in the number of purveyors of fake passports. By August, the Israeli company estimated that there were around 2,500 active Telegram groups across Europe offering fake certificates, with an average of around 100,000 followers per group – in some cases the number rose to 450,000. The delta coronavirus variant was spreading rapidly. Anyone who wanted to have an apparently valid certificate without vaccination had to pay $100 (€88) on average.

By September, Check Point Research had more than 10,000 alleged distributors of fake Covid passports on its radar. The demand was such that a Telegram bot was even detected in Austria manufacturing fake certificates: after entering the personal data of the person concerned, he or she would receive a PDF with the QR code.

Another tactic, discovered in September, involves claiming to have access to a supposed European database of vaccinated persons. These cybercriminals offer to register interested parties on the database in exchange for money. But the database does not exist.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.