Artificial intelligence and digital extractivism: Who benefits from data centers in Latin America?

OpenAI has announced the construction of a mega data center in Argentina, the latest of its kind in the region. Governments should demand local participation and reinvestment terms that promise more than free access to ChatGPT

In July of this year, I flew 11,000 kilometers from Buenos Aires to take a course on artificial intelligence policy and law at the University of Leuven in Belgium, a vast neo-Gothic structure founded in 1425 where today, across its various campuses, 57,000 students study a wide variety of disciplines. Halfway through the class, the lecturer divided us into groups and gave us the assignment for a group exam: “The environmental footprint is overrated.” And I panicked. But there I was, faced with a classic and effective academic exercise: supporting a position with arguments, even if they aren’t your own.

Once I got down to work, I confessed to my colleagues that it would be difficult to defend an argument that was untenable on all counts. As a Latin American, I followed the news about the socio-environmental impact of new data centers built in recent years in Querétaro (Mexico), Santiago (Chile), and Rio Grande do Norte (Brazil), which were added to those developed in regions with proven water scarcity, such as Arizona (United States) or Aragón (Spain).

With little evidence, my group outlined their arguments: that common metrics for measuring the environmental impact of AI still don’t exist worldwide, that it was impossible to separate AI’s footprints from other technologies associated with it, that other industries pollute much more (this one made me feel like I was in second grade), and that early technologies always cause more impacts than benefits. My group passed. Fortunately, the final exam was an essay in which I defended another idea: if the debate on technology policies remains stuck in the false dilemma of regulation that stifles innovation, large technology companies will continue to advance, hand-in-hand with local allies who have little interest in the well-being of their communities.

The mega data center of optimism

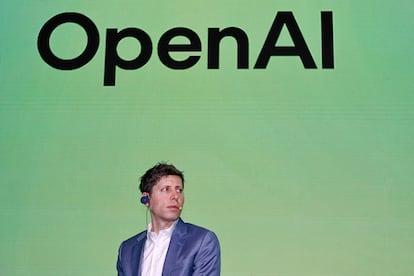

Three months later, on the morning of the National Day of Cultural Diversity holiday (which President Javier Milei rebranded as Columbus Day), Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, announced a $25 billion investment to build a mega data center somewhere in Argentine Patagonia. The news came after a political-economic negotiation between the Argentine president and Donald Trump, in which Scott Bessent, the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, had stated that his country was “buying low” to “sell high.” Bessent did not clarify which goods he was referring to, but hours later, Altman revealed a preliminary agreement to build artificial intelligence infrastructure and computing capacity for his company. The project, he noted, would be part of Stargate, with its partner Oracle and its venture capital funders, Japan’s SoftBank and the Emirati company MGX. In Argentina, a little-known company called Sur Energy (backed by renowned tech entrepreneur Emiliano Kagierman) would be in charge of local management.

The project, which promises to produce 500 MW of power in its final phase, could also benefit from the RIGI (Renewable Energy Act), a law passed under Milei’s administration that guarantees entrepreneurs 30 years of tax exemption and protection from disputes in exchange for foreign currency. The project also offers entrepreneurs the right to hire local employees and lax conditions for purchasing from local suppliers.

Days later, with Milei and Trump on screen from Washington, OpenAI published an official statement: “This milestone is about more than just infrastructure, it’s about putting AI into the hands of more people across Argentina.” Nowhere in the communiqué was there any mention of employment, contracting for local industrial production, environmental impact assessments, or oversight of strategic infrastructure.

Even though the agreement seemed like something “from the 16th century, when the silver from Potosí financed European empires and left the region in poverty” (as engineer Luis Papagni wrote), much of the tech world expressed euphoria. “This will bring other investments. Where OpenAI goes, others will come,” said a digital marketing speaker on television, while journalists and panelists nodded in agreement. How could this benefit for our country be proven without clearer regulations and socio-environmental impact assessments? The media’s optimism was such that the question, for now, was irrelevant.

Extractivism or production?

The question, though old, remains fundamental. Argentina (and other countries in the region) have more than attractive conditions for Big Tech investments: vast stretches of sparsely populated land, areas with water and mineral resources, nuclear and hydroelectric plants, and highly qualified personnel trained at world-renowned public universities. For its part, OpenAI faces a crucial problem: its dependence on computing power from companies like Google Cloud, Amazon Web Services, Azure, and Oracle. Even for a novice negotiator, the strategic advantage for our countries would be clear. Or, at least, the possibility of an exchange with more demanding conditions. SoftBank, which was also a major investor in Uber, knows this: the ride-hailing company had to relax its conditions in order to operate in cities like Madrid, Barcelona, and London, allowing hybrid systems that wouldn’t suffocate local drivers.

In the case of environmental impact, the data is eloquent. In Querétaro, in the areas where these facilities operate, the government had to ration water, and some families receive service only every three days. Furthermore, the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) was forced to increase the generating capacity of nearby power plants (which use fossil fuels) by 50% due to the consumption of data centers. It’s clear: in the case of technology companies, but also in other resource-intensive industries such as mining, trade-offs are necessary. For some regions with decades of poverty and joblessness, the arrival of investment presents an opportunity — at least momentary — for progress. The trade-off is not simple. However, for this benefit to be more than temporary, something more is needed than faith in the economic “trickle-down.” National and local governments should demand, for example, local participation in employment and inputs, and future reinvestment conditions that promise more than just free access to ChatGPT for local people, as happened in the United Arab Emirates with the construction of a Stargate data center.

Ultimately, none of this happens in a vacuum. Since taking office, the Milei administration has been engaged in a dispute with public universities, denying them the budgetary allocation they are entitled to under the law, which would amount to a tiny fraction of an investment like the one proposed by OpenAI. The initiative’s local partners, such as Emiliano Kagierman, are world leaders in technology, trained in that university and public science system that is currently struggling to survive. The CEO of this successful satellite innovation company acknowledged this: “We were able to do it because there had been (in Argentina) 40 years of systematic investment in technology, in the space and nuclear sectors.” And he admits that, for his company, the support of the Ministry of Science and Technology and INVAP, a company dedicated to the development of complex technologies, “are a textbook case of what the State can do to open up opportunities and provide capabilities.” Perhaps true progress lies in returning some of these investments to their roots: to that system of universities and public science that, even in crisis, remains the reason we are now part of the global map of artificial intelligence.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.