Where do the clothes go after we put them in a recycling bin? An 11-month investigation covering thousands of kilometers

EL PAÍS followed the path of 15 geolocated garments for months and over thousands of kilometers to gauge the environmental and social costs of the mass consumption of fast fashion. Dubbed in Africa as ‘dead white man’s clothing,’ it pollutes countries in the Global South, feeds opaque commercial networks and leaves a long carbon footprint in its wake

On the beaches of Accra, the sea vomits up old clothes. The sand in Akuma Village is covered with a carpet of shoes and plastics entangled with shirts, shoelaces and pants. It’s just the tip of the iceberg of what is currently floating in the ocean. A few miles away on solid ground rises a series of multi-colored hills. This is no idyllic landscape, but rather, gigantic mountains of used clothing that has come from Europe, China and the United States. Some are on fire, emitting black toxic smoke from the combustion of synthetic fibers. It leaves the air thick, sour-smelling.

Ghana is an extreme case, but it’s not the only example of how countries throughout the Global South such as Pakistan, Kenya and Morocco play a fundamental role in the system of hyper-production of cheap clothes. These are the places that make it possible for us to buy shirts we don’t need and dresses we’ll wear once, or never. They are the textile landfills that sustain “fast fashion,” which in countries like Ghana has led to an environmental and public health disaster. In Africa, it’s known as “dead white man’s clothes” and some nations like Uganda, Rwanda and Zimbabwe have prohibited or restricted the importation of what they call “textile neocolonialism.”

To learn how we got here and exactly what happens when, with all the good intentions in the world, we deposit a garment in a secondhand clothing donation bin, EL PAÍS embarked on nearly a year of investigation that has allowed us to corroborate the final destination of 15 garments whose path we followed, thanks to geolocation technology. The results were revealing. The majority continue circulating or are in warehouses or empty lots. Half have traveled to foreign countries, leaving a monumental carbon footprint in their wake, contaminating the Global South and feeding into opaque commercial networks. That is to say, clothing doesn’t always end up in the place we imagine when we get rid of it and even when it does, the ecological footprint of its journey is immense.

The root problem, according to experts, is the unbridled production of cheap clothing. They say that, despite the current system’s failings, depositing garments in donation containers is still the most sustainable option. In Spain, exports of used clothing have skyrocketed in recent years due to the country’s inability to absorb the number of garments that are bought and discarded.

15 hidden AirTags on garments that have traveled the world

Last March, we asked EL PAÍS staff to bring clothes they no longer wore to our headquarters in Madrid. We sewed AirTags into each of the 15 garments, hiding them in folds and pockets so that they weren’t visible at first glance. These devices allowed us to geolocate the pants, shirts and jackets thanks to a signal they emitted every time they got close to a phone. There was just one problem: the device would beep when this happened, revealing its presence. A technician from Greenpeace made our job easier by removing their capacity to beep and just like that, the AirTags became our silent allies.

We sent the garments throughout Spain with the help of the newspaper’s various local offices, each of which deposited an item in a secondhand clothing donation bin. In addition to this geographic balance, we tried to make sure that a variety of distribution networks were represented: containers operated by department stores, NGOs, local councils. The clothes immediately began to broadcast signals, and from then on, we could see where they were at any given moment.

Eleven months later, many of the garments were still on the road and seven of them had traveled abroad to Africa and Asia. Three of them passed through or stayed at distribution points in the United Arab Emirates. One pair of Minnie Mouse pajama pants made in China, which were deposited in April into a container in Zamora, Spain, passed through Madrid and then flew to the Emirates, where it reported from a warehouse owned by The Cloth, a textile and clothing recycling company that claims to process 1,200 tons of garments every month.

A black bullfighter-style jacket made in Morocco and discarded at a Madrid H&M container traveled through the Netherlands before ending up in the UK in a factory that shreds clothing to turn it into other fabrics. Beige trousers made in China were found in a shopping area in South Africa, as a contributor to this newspaper was able to verify, after first passing through Italy, Abu Dhabi, India and Mozambique. Light blue ripped jeans made in Turkey were tossed into a container in San Sebastián and months later, appeared in the Emirates and from there, were sent to Ghana. They then traveled to Ivory Coast, where they were found on the outskirts of the capital. Others are still in industrial units in Spain or in empty lots, like a black coat whose AirTag places it in an industrial estate in Montaverner, Valencia, in an open-air fenced enclosure where bales of clothes sit, as reported by EL PAÍS journalist Andrés Herrero Gutiérrez. A pair of boy’s pants were deposited in an A Coruña container and emitted their last signal on February 4 in an industrial estate in Ferrol, Spain.

This experiment represents a minuscule sampling, but serves as a good illustration for the way tons of clothing move around the world. Several of the garments are still traveling, but so far, the seven that have left Spain have gone more than 65,000 km (40,400 miles) since they were dropped off. And that’s not counting the more than 36,200 km (22,500 miles) that had already been traveled by the seven garments between their manufacturing sites and Madrid, where they were taken to the EL PAÍS headquarters.

These are the garments EL PAÍS tracked:

These results are in line with those from a European Union study that found that, regardless of whether garments are donated to a non-profit, they typically enter into a commercial market. The price for a pound of secondhand clothes is around 36 cents. In Asia, clothes are bundled in industrial areas, where they are re-exported to other Asian or African countries. 40% of exports to Africa end up in landfills, according to the same sources. Furthermore, 89% of these garments contain synthetic fibers, which will decompose into microplastics with toxic chemicals that contaminate the soil, water and air, leading to serious public health issues.

“As reuse and recycling capacities in Europe are limited, a large share of used textiles collected in the EU is traded and exported to Africa and Asia, and their fate is highly uncertain,” states a document from the European Environment Agency, which argues that “the common public perception of used clothing donations as generous gifts to people in need does not fully match reality.”

The data is clear. We buy more clothes, at lower prices, and we use them for a shorter amount of time. The European Union alone generated 6.94 million tons of discarded textiles in 2022 — around 16 kg (35.3 pounds) per person. Of that, 15% was left in recycling centers and the rest ended up mixed in with domestic waste, according to data provided by the European Environment Agency and the European Center for Circular Economy and Resources that will be published in March.

The amount of used textiles that is exported from the EU tripled during the last two decades, going from 550,000 tons in 2000 to 1.4 million tons in 2019. The volume that was collected and sent to other countries is expected to increase considerably due to the requirement to collect textile waste separately in the EU, according to the EEA. This new directive, which came into force in January 2025 and which in Spain is regulated through the country’s Law on Waste and Contaminated Soils, requires town councils and companies to install more containers for the selective collection of used textiles in order to encourage reuse and recycling.

Spain is the eighth EU country in terms of textile waste generation. Foreign trade data shows that last year, used clothing exports amounted to 164,274,577 kg (362,163,449 pounds), according to data that was released this week. This represents a sharp increase from 129,705,188 kg (285,950,992 pounds) in 2019. The United Arab Emirates (a hub from which clothes are exported back to Africa, as we were able to verify with some of our trackers in the course of this investigation), Morocco and Pakistan are the primary destinations of these garments.

Albert Alberich is the director of Moda re-, a social cooperative promoted by the Catholic Church’s organization Caritás that has handled three of the garments that EL PAÍS deposited in donation boxes. He estimates that between 700,000 and 800,000 tons of textile waste end up in landfills. “It’s an outrage. The challenge it represents for our society is brutal, because we have to reduce consumption and choose higher-quality garments,” says the executive, who adds his organization does not have the capacity to dispose of all the garments they receive, which forces them to export.

The United Nations Environment Program calculates that between 2% and 8% of polluting emissions come from the textile sector and that projections indicate that this figure is set to skyrocket in coming decades. The textile industry also consumes 215 trillion liters of water a year, the equivalent of 86 million Olympic swimming pools, and generates 9% of the microplastics that pollute the ocean.

This environmental impact increases dramatically if we take into account the garments that are destroyed in Europe before being worn, another perverse effect of the current fast fashion system. Figures indicate that between 4% and 9% of all garments sold in Europe are destroyed before being worn, which means that between 264,000 and 594,000 tons of textiles are destroyed every year. This phenomenon has a lot to do with the return of garments purchased online. In Europe, consumers return about 20% of the clothes bought online, three times more than those bought in a physical shop. About a third of returned clothes end up being destroyed.

Furthermore, experts warn that clothes are decreasing in quality, becoming increasingly less recyclable and durable. “On the one hand, there is the increase in the amount of clothing that has been produced in the last 20 years, which multiplies the amount of waste that is generated,” says Sara del Río, a Greenpeace researcher. Data reveals that, for example, production of textile fibers reached an all-time high last year. “But, on the other hand, there is also the issue of quality, which is getting worse and has clear consequences for the environment,” says Del Río. Her organization estimates that half of the garments that arrive in Ghana, for example, are of poor quality, have no possibility of being sold again, and are made of synthetic fibers.

Del Río welcomes the new law that requires the separation of textile waste, but fears that such solutions only affect “the end of the pipeline.” “If we focus on waste, but do not attack a production system that generates more and more polluting goods, the problem will not be solved,” she says.

Ghana, the great used clothing dump

Chilies, ginger, scouring pads, plastic flip-flops, shoelaces and tons of used clothing. The humidity and heat inside the bustling Kantamanto market is suffocating. It is a labyrinth of narrow alleys full of people, with piles of goods everywhere. The clattering of hundreds of thousands of treadle sewing machines serves as background music at the market, where tons of used clothes from industrialized countries arrive every week. The movement of bales of clothes that are pressed and stacked in vans is continuous. They come from Korea, the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom. The material is displayed in precarious and colorful stalls. A three-quarter coat, in defiance of the unrelenting heat. A down jacket alongside a mountain of military clothing. An abandoned railway line traverses the market from end to end. On its tracks, recently washed jeans dry in the sun.

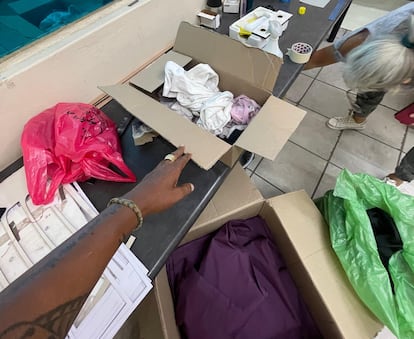

The owners of these stalls buy bales by weight, without knowing what’s inside them and with no guarantees. “It’s like a lottery. You don’t have the right to return it and you don’t know what the quality is going to be until you open it,” says 43-year old Vida Oppong. Last night, the trucks arrived loaded with big bales of used clothes and today, Friday, Oppong is opening them one by one. She buys from wholesalers, who in turn buy from intermediaries who obtain the goods from NGOs and other organizations. Oppong inherited her business from her mother. She advertises the clothes that arrive in WhatsApp groups and on social networks.

A new 55 kg (121 lb) bale arrives, which cost her 20 cedis ($1.31). It’s heavy, because the clothing has been pressed. She cuts the black straps that bind it and opens the massive package, which has come from the UK. She will later use the straps to make baskets — here, nothing is thrown away. She finds a black Primark jacket, then another from Next and a third from Zara. Then comes one that was originally white and now has a yellowish tinge. Another, with a pen still in its pocket. Oppong has a preference for dark denim because lighter shades need to be sometimes taken to the drycleaner’s before they are sold. If it’s not in good condition, she’ll rip it so that it’s “more punk.” Sometimes, she’ll just use the fabric to make denim bags. Other traders agree with her assessment that in the last five years, the quality of the clothes arriving has declined considerably.

“Before, when you went to the market, you could even find Chanel. Nowadays, the North keeps the best and sends us the trash. It’s pure textile colonialism”—Kwamena Boison, co-founder of Revival

Kantamanto is considered the prime model of a circular market in which thousands of entrepreneurs work to give second life to what people in other countries have discarded. The problem is that the enormous efforts of Kantamanto’s traders are clearly insufficient. Much more arrives than can be reused and, in addition to the used clothes, tons of very cheap new garments are received, a production surplus with which it is impossible to compete. What is not processed ends up being incinerated in gigantic landfills. Their capacity to recycle was further reduced on January 1, when the market burned down and thousands of people were left without a livelihood. They are now trying to rebuild.

Kwamena Booison, co-founder of Revival, a Ghanaian organization that is dedicated to clothing recycling, talks about how “fast fashion is destroying the local textile industry. Secondhand clothes are so cheap,” he laments. He believes that the quality of the clothes entering the market needs to be regulated. “Before, when you went to the market, you could even find Chanel. Nowadays, the North keeps the best and sends us the trash. It’s pure textile colonialism,” he says. His organization works hand in hand with Kantamanto entrepreneurs to try to intercept clothes that would otherwise wind up in the ocean. His organization estimates that between 10% and 40% of what arrives is unusable, although the secondhand clothing trade association says the figure is lower. Boison is clear that we are facing a worldwide problem. “Societies have to get involved to find a real solution. There has to be a global plan for the North and South.”

Branson Skinner, co-founder of Or Foundation, which fights against textile waste, defends the work of the Kantamanto entrepreneurs at his headquarters in central Accra. “They are not the problem. We have to attack the root cause, which is the business model.” He thinks that “if Europe was serious about recycling, it would support these people. They do the dirty work.” His organization estimates that before the fire at Kantamanto, 25 billion garments were recycled every month. Today, representatives from several European cities have come to the offices of the Or Foundation to see what they can do to ensure that the companies operating in their own cities fulfill their responsibility to take care of the waste they generate. Liz Ricketts, the director of the foundation, thinks that the only way forward is to extend producer responsibility and to make companies’ production figures more transparent. “In 2011, when we started, there was no textile waste on the beach. It’s all happened very quickly,” says Ricketts.

Ricketts’ foundation, which is financed by fast fashion chain Shein, has built a used clothing recycling center in Kantamanto that experiments with fibers in the manufacturing of clothing hangers, photo frames, cushions and even speakers. They pick up clothing from the beach and divide it by color, shredding it and mixing it with cassava starch. They use this material to make between 100 and 150 products a day, a process that generates job opportunities. The problem is that it represents a mere drop in the ocean.

Tons of clothing that are not processed in Kantamanto wind up on the beach or burned in landfills. Infrared analysis carried out by Greenpeace in Ghana has found that at least half of these garments are made from non-biodegradable plastics that end up as polluting microplastics. In the case of the Accra landfill sites, part of the energy released by the burning of the mountains of clothing is used to heat water in public baths. At least three of the baths have registered the presence of toxic substances, including carcinogenic elements.

The business of crossing from Melilla to Morocco

The Mediterranean waters that lap the shores of Nador do not wash up unwanted clothing. In this Moroccan city, located less than 20 km (12.5 miles) from Spain’s exclave city of Melilla, the business generated by European used and discarded clothing looks different to that of Ghana. Its previous iteration, in which large amounts of clothing were carried over the border from Melilla into Morocco, dried up in 2018, when Morocco unilaterally closed the commercial border between Beni Ansar and Melilla. But the industry’s new form enriches a few and exploits many, condemning thousands of people who once lived off this activity to a fraudulent and even more precarious trade, not to mention, the struggle for mere subsistence.

“15,000 people used to make a living working between Melilla and Morocco,” among them thousands of Moroccan porteadoras [women who carry heavy bales of clothing and other items on their backs as they cross the border], says Omar Naji, a member and former coordinator of the Moroccan Association of Human Rights (AMDH) in Nador. With hardly any alternatives when it comes to jobs in a region that “had always lived off smuggling,” the closure of the border plunged Nador into a deep crisis. Its latest population census confirms, according to Naji, that the province is losing population. “People are emigrating because the socioeconomic situation is so bad,” adds the activist.

The journey made by a red cloth coat that EL PAÍS deposited in a donation box in Guadalajara managed by East West, a company that presents itself as a promoter of environmental care, neatly illustrates the story of former smugglers who have been pushed back into the informal economy in order to survive. After traveling some 1,600 kilometers by land and sea and passing through Murcia, Cádiz, Algeciras, Tangier, Rabat and Meknes, the garment arrived in mid-September in Nador, specifically in one of the warehouses in an informal market of former smugglers.

From then on, its AirTag has continued to emit a signal that indicates that it hasn’t moved. Faruq keeps tabs on who comes and goes from this solitary building, constructed with money contributed by the smugglers themselves “on land they rent from the state.” Only the clanking of the metal gates of the surrounding warehouses breaks the prevailing silence. The noise is a sign that a merchant is loading or unloading bales of clothes. Like Faruq’s brother, who places on a motorized cart an enormous sack from which a maroon shoe sticks out.

They’re not entirely comfortable that journalists are there to witness them. But Faruq, whom everyone treats as the warehouse boss, will not call the police, unlike others in Nador who are apt to do so at the mere sign of a video camera. He can’t. “The police keep us very oppressed,” acknowledges the man, who worked for more than 20 years smuggling clothes between Nador and Melilla and who prefers to use a fake name and hide his face from the camera’s lens. “The companies we buy from don’t invoice us,” he says to justify why he avoids the police, while opening the door to one of the storage rooms full of “75-kilo” (165 lb) bales of clothes.

Faruq and his people’s way of life has evolved from smuggling to another kind of informal business in which their only option is to irregularly acquire garments that they will later resell. They cannot legally import secondhand clothes without a license. The Moroccan government has only granted them to a handful of companies, as Naji confirms, and the former smugglers, who have organized into a kind of union led by Faruq, have been trying for years to obtain one of these permits. They can hardly buy used clothes legally from licensed Moroccan companies, because the permits only allow those firms to sell around 20% — though the percentage can vary — of their product on national territory. The measure is designed so as not to harm the Moroccan textile industry, explains Naji. So the only option, says Faruq, is to buy without an invoice. Both parties win: the former smugglers will benefit from cheaper merchandise and the importers will find a market for their product in Morocco, where secondhand clothing markets are everywhere.

In the Yutiya market, one of many located in the region, Faruq has various points of sale. Among the piles of clothes in these souks, one can find anything from a 100% cotton jumper in perfect condition for 10 dirhams (about $1.05) to wedding dresses and Dr. Marten boots for 50 dirhams (less than $5.25). Everything — or just about — is likely to be resold: pajamas, jackets, belts and even mountains of bras and underwear. At a stall selling backpacks hangs one that was apparently once used by a little boy named Hugo, according to the name written in black marker on one of its pockets. In another stall hangs a uniform from the multinational logistics company DHL, and a T-shirt from a Spanish plaster cast company. There is so much clothing that one seller spreads a gray dress out like a carpet to prevent buyers from tracking mud into his stall on a rainy afternoon.

Prices vary by quality and the state of the garment. Faruq breaks down the categories: the “cream” clothes, from the French expression la crème de la crème, “are top-level” and are bought by traders at around 150 dirhams ($15.30) per kilogram, with the pieces later sold for 400 dirhams ($41) apiece. “They’re expensive brands,” he says. From there, the clothing is divided into groups “one”, “two” and “three”, with prices ranging from 70 to 15 dirhams per kilogram.

Fatima is accompanying her nieces to the Aroui market, located alongside Nador airport, all the way from Oujda, which is 93 miles away. “I find good quality secondhand clothes,” she says. On this day, after four hours of searching, she’s acquired a pair of Timberland boots that “cost 1,200 dirhams new, for just 150,” she says with evident pride.

But the murkiness surrounding the secondhand clothing business in Nador goes beyond the sale of untaxed goods. Months after the border was closed, Karama Recyclage (its name comes from the Arabic word for “generosity”) was built on a plot of land facing the port of Beni Ansar. Karama is a used clothes management company financed largely with public money to provide an outlet for those who could no longer smuggle goods. “The bid [for the license to import secondhand clothes] required the applicant to employ between 800 and 1,500 people affected by the closure, mostly women porters,” explains Naji. But the reality of the situation contrasts with these initial expectations. The company is the only one in the Nador province that holds a license for the importation of used garments, a fact the activist denounces because of the “monopoly it represents.” Furthermore, “half of those who work there have never been involved in smuggling,” says Naji, who says that the porteadoras, who are mostly women over the age of 50, have been left behind with few options for survival.

Those who have found work at Karama are not much better off. “Not all of them are paid the minimum wage or are registered with the social security system. They have problems with overtime, they are not allowed to go to the bathroom, and are subject to verbal abuse,” says Naji, referring to testimonies that his association has collected from Karama employees. Four women, according to the activist, reported sexual abuse and abusive body searches by security guards to the AMDH in Nador, but failed to see that the company made any changes. “It also employs the strategy of not paying employees for two or three months and even firing them to make them protest, and thus, be able to put pressure on the Public Administration and the Ministry of Industry and Trade to renew their license,” which must be re-issued every six months.

One former Karama worker, Saleh (not his real name), corroborates these reports. “There is a lot of exploitation, they frisk you in an abusive way and then they accuse you of having stolen clothes, even when they’re your own garments.” After four years, he left his job after becoming injured by a forming press and failing to receive any compensation. EL PAÍS has attempted to obtain a comment from Karama Recyclage on these claims by telephone, email and even by knocking on the company’s door, but did not receive any response.

Faruq does not buy goods from Karama. “What we were buying before for 30 dirhams, they try to sell to us at 120,” says the man, who prefers to do business with firms in Tangier, through which the red cloth coat tracked by this publication passed. Faruq looks again at the bales.

— Do you come across torn garments sometimes?

— Of course, and in very bad quality.

— And what do you do with them? Do you recycle them?

— We have to throw them in the trash.

Separated by law

Since January 1, 2025, the collection of used textiles has been mandatory in EU countries in order to reduce waste and encourage recycling. One of the objectives is for textile producers to be responsible for the entire life cycle of their products, from their design to how garments are discarded. In Spain, this regulation is part of the Waste and Contaminate Soils Act, which requires that by 2025, it must be possible to reuse or recycle at least 55% of household waste, including textiles. That percentage will increase to 60% in 2030 and 65% in 2035. For practical purposes, local governments and clothing brands will have to install more containers to collect textile waste separately, in addition to those already managed by non-profits. At the same time, shops will not be able to throw away unsold surpluses, which must be sent “firstly to reuse channels.”

Some companies have been collecting used clothes for years. In 2015, Inditex launched a program that placed containers in all its stores to facilitate the recycling of clothing. “The garments are collected by the non-profits with which we collaborate, although our main partner is Cáritas, which manages the clothing through Moda re-,” company representatives explain. A sweatshirt that EL PAÍS deposited through this program in a Zara store in the Isla Azul shopping center in Madrid arrived last May at a Moda re- warehouse in the Atalayuela industrial estate in the capital. It has been there ever since, although two other geolocated garments were deposited at the same store traveled as far as the United Arab Emirates. “One of the conditions of our agreement with Moda re- is that our garments cannot end up in a landfill or in a certain number of countries where adequate treatment cannot be guaranteed,” say the same representatives, who would not confirm which countries were on the banned list.

H&M also has a similar clothing collection program featuring containers in its stores. “Clothing that can be reused is sold secondhand. This represents approximately 60%. Clothing and textiles that cannot be resold are reused or mechanically recycled into new products and fibers, for example, in products for industries such as automotive, construction or cleaning rags,” company representatives explain. One of the 15 garments, a black bullfighter-style jacket, ended up in the United Kingdom at Edward Clay Wood, the headquarters of a felt manufacturer in Osset.

Moda re-, the cooperative in whose facilities three of our geolocated garments wound up, operates four used clothing treatment plants in Bilbao, Barcelona, Valencia and Madrid. “In 2024, we collected more than 45 million kilos (99 million lb) of clothes,” says Alberich. The executive clarifies that, according to the latest studies that have been made available to him, institutions like his collect a total of “between 105 and 110 million kilos (231 and 243 million lb)” every year. “But that’s still very little if you take into account the estimates that have been made that between 700,000 and 800,000 tons of textile waste ends up in landfills,” he said.

“We don’t have the capacity to sort all the clothes that arrive to Moda re-, although that is our goal,” says the director of the organization. In fact, the quantity of garments they receive is such that they have moved from a 64,600-square-foot facility to a 25,900-square-foot space in Barcelona. Despite this, they are still unable to find an outlet for many of garments. Those that they cannot process and classify are “mostly exported to the United Arab Emirates, because the country has become a hub for processing used clothing.” Of the three EL PAÍS garments that were processed by Moda re-, one of them is still stored in a Madrid warehouse, while the other two have been transferred to the Emirates. One of them traveled to Johannesburg.

According to Alberich, between 50% and 55% of the clothes that Moda re- processes is reusable and between 30% and 40% is recycled and turned into other products, because it’s not “suitable for being reused.” But of the reusable clothes, only 10% wind up in one of the organization’s retail locations throughout Spain, a country that, according to him, “doesn’t have much of a tradition of wearing used clothes,” as they are still associated with a “certain stigma.”

Again, he turns to data to compare countries. “In Spain, there’s no more than 300 secondhand clothing stores, including those operated by Moda re-, Humana and other non-profits,” while in the United Kingdom, “non-profits alone manage 11,000 establishments.” “In Spain, clothes could be reused much more than they are,” he says. Clothing classified as reusable that is not sold in Spain is exported to Africa. “It is very difficult to prevent the garments from ending up in Africa while the waste hierarchy [of the European Union] remains unchanged, which means that we cannot recycle a garment that is reusable,” explains Alberich. Although, the “big secret,” he says with conviction, is in the “first ‘R’, that of reducing consumption.”

In May 2024, new European regulation on waste shipment, including textiles, came into force. It aims to eliminate the impact of waste shipments to developing countries, promote the traceability of waste shipments within the EU and facilitate their recycling and reuse.

This month, the European Union reached a provisional agreement to revise the waste framework directive by extending the responsibility of producers, who will have to pay a fee to finance the sorting of clothing and the processing of textile waste. Member States will be responsible for deciding on concrete measures to combat ultra-fast fashion.

Non-profits have welcomed these new norms, but fear they will be meaningless if the ability to manage waste recycling does not increase. If it doesn’t, a significant portion of this waste could still be sent to countries outside the EU. And still, the underlying problem, as pointed out by Greenpeace researcher Del Rió, is that the model of overproduction of clothing remains unquestioned.

Despite this, non-profits insist that consumers should not stop donating their used clothes, and that the containers currently provided for that purpose continue to be the most sustainable alternative. “Recycling and reuse work and a lot of progress has been made. We network with fashion companies and with public administrations. We don’t have all the answers, but what we can’t do is slow down. We are all a part of the problem and a part of the solution,” says Nati Yesares, head of the environmental department at the non-profit Solidança, which collects 7,700 tons of clothes every year that it then sells in its secondhand stores and exports to clients, the majority of which are Africans. “They’re products, not waste,” says Yesares, whose group has created more than 300 positions, 180 of them for disadvantaged groups. She says that one of the most urgent tasks is to find ways to better recycle textile ways, “in a circular manner and in Europe.”

The idea that the countries of the Global South will be capable of recycling materials that Europe exports due to its inability to process them sustainably is unrealistic. The low quality of the clothing that arrives in those countries often prevents its reuse. But while new laws are passed and the production system considers correcting its excesses, on the outskirts of Accra, foul-smelling fires continue to burn through mountains of clothing, with no end in sight. The garments tracked by EL PAÍS continue to reveal gaps in an increasingly unsustainable system. We will continue to report on their whereabouts.

Translated by Caitlin Donohue.

Credits

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition