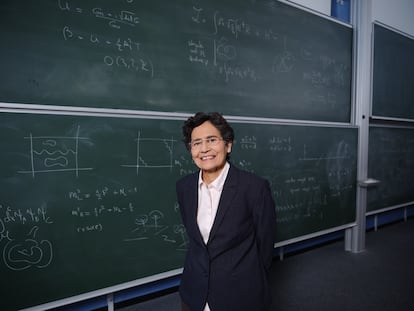

Anamaría Font and the achievements of women scientists

The Venezuelan physicist has contributed to the study of string theory, for which she was awarded the UNESCO L’Oréal International Prize

At the beginning of 2023, Anamaría Font, 64, was in her native Venezuela. She returned to the Faculty of Sciences at the Central University of Venezuela (UCV) in Caracas after the pandemic; for many Venezuelans traveling back and forth between countries, the Covid-19 years ended up becoming a definitive departure. There, she met with students of the Mathematical Methods for Physics course that she had taught since 1989. Some of them had taken over as professors of that same course. “I became a scientist thanks to the environment I was in; I lived in a time of opportunity. I was happy to meet some young women I taught in classes; [they are] very intelligent and motivated,” says Font in a video call from Potsdam, Germany, where she now lives permanently. The pleasant surprise with which she returned to Germany was accompanied by a nagging concern. “Now everything is very difficult for young people in Venezuela. Going to university is like an act of love or a sacrifice.”

A few months ago, Font received the International Prize for Women in Science, awarded by UNESCO and the L’Oréal Foundation. Her contributions to the study of string theory, which attempts to explain elementary particles and their interactions not as points but as strings, won her the prize. Proposed in the 1970s by Jöel Scherk and John Henry Schwarz, string theory could provide a solution for the problem of combining gravity with quantum theory; it has become an important branch of physics.

Font explains that her foundation in this theory was a country in which she could take advantage of better times than the present. “I think it was because of the environment that I had there. I was born in Anaco, but I grew up between Puerto La Cruz and Margarita. My dad worked at the Ministry of Mines and Hydrocarbons, and I studied at Sinclair Oil Company’s elementary school. Oil led me to string theory, somehow,” she recalls. “I became interested in physics in high school… I attended a public high school, and what we studied then was at the level of what is now done at the university level. We had well-equipped laboratories, and I had three teachers for physics, chemistry, and mathematics who knew a lot. It was the best way to motivate me!”

Font has always been surprised by the number of women at universities and in scientific careers in Latin America, although there are fewer in leadership positions, such as university rectors and deans. In Venezuela, she says, the proportion of women in the sciences is high compared to Europe. For example, she observes that at least 30% of physics professors at UCV are women; in other areas like chemistry and biology, there are as many as 50%. “In Germany, there are far fewer women doing science at universities and studying it. Surely, there is a different family culture about what is (and is not) expected of women. But there is a conscious effort to change that, and in southern European countries the proportion of women is increasing. In Venezuela and Latin America, science departments are relatively recent, from the late 1950s on, and their founding coincided with the time when more women started to attend universities, so I think that is why we see more women, because there isn’t the historical weight of exclusion [there]. Women have a harder time [in places] where there is more of a scientific tradition.”

Font recognizes the difficulties for women in science and the bias against them. “To move up in the scientific ranks, one’s number of annual publications is taken into account in the same way whether you are a man or a woman. Little by little, that is changing, but when you’ve had a child, you probably could not produce any [scholarship] for a year, and that year should not be counted. There are still a lot of cultural biases, like moms and grandmothers of girls who believe that going into science is not for women, that it’s a difficult subject for women. When I started in string theory, there were very few women, but now there are many young women in this field, and many of them are from Latin America.”

Science amid economic precarity

Font graduated from Simón Bolívar University and then continued her studies at the University of Texas, applied for government scholarships and funding from research centers and foundations, and returned to Venezuela many times. She says that those conditions allowed her to build a scientific career when she was starting out, but now they are not available amid Venezuela’s deep economic crisis (the country has the highest inflation in the world). That situation prompted her decision to leave home with just one suitcase, like the millions of Venezuelans who have formed a huge diaspora. “My only income there is my university salary; including some bonuses, it amounts to 1,600 bolivars ($50), which is not enough to live on.” Over the years, it became increasingly difficult to go back and forth between Venezuela and Germany, where her husband is from.

Universities have been among the hardest hit by Venezuela’s economic crisis. Nicolás Maduro’s government undertook improvements in the infrastructure of the UCV, the seat of which is located in University City, a World Heritage Site, where Font taught for almost 30 years. But little has been done to rebuild the human capital that makes it possible to produce knowledge.

Venezuela’s “brain drain,” the exodus of the most qualified professionals, began the flood of migration that the country has experienced in recent years. Doing science in a precarious and highly politicized environment over the past two decades of Chavismo has become an uphill struggle. Fewer people are doing research, and those who go abroad to do their doctorates do not return. “When I was there this year, I saw that lack of future for young and not-so-young people. That is why my biggest worry is that it will be impossible for the university to recover, that it will remain in permanent decline.”

For Font, science has a place even in hostile scenarios, where there are other pressing issues like poverty, but its study must be supported by independent institutions. “A sustainable effort must be made to attract young people to science; it isn’t done until elementary school.” She defends science as a universal human value, as a way to solve problems, but in Venezuela Chavismo has sought to establish a distinction between so-called relevant science and science that does not address the country’s development. Font issues a plea about the general sciences and the theoretical physics that both occupy and amaze her. “There is no doubt that basic scientific research is crucial for development. You never know where the solution will come from, and history tells us that it can take years to achieve results in the general sciences and their applications. When they combined electricity and magnetism, they never imagined the impact it would have on telecommunications years later. You can’t say that there is only one kind of science to be done.”

Font continues to be active in research and is interested in the development of cosmology — explanations of the universe’s origins — which is part of what is going on in her field. “There is a lot of overlap between theory and experiments; terrestrial observatories are sending data all the time, and there’s additional information from gravitational waves. There is also everything we can find out about particle physics in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC, the largest and most powerful particle accelerator, which the European Organization for Nuclear Research built in Switzerland), which is the best model we have, and we have to find out if it explains everything. These are some of the things that most interest me right now.”

As a scientist, she is enthusiastic about medical advances to achieve a better understanding of how the human body works and the origin of diseases at the genetic and cellular levels; she is also somewhat concerned “that a new space race is beginning among the world powers to find extraterrestrial resources to exploit.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.