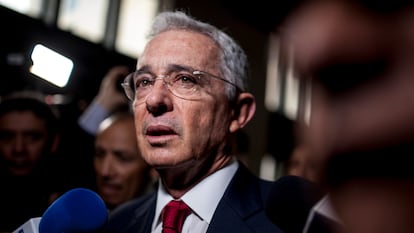

Release of Álvaro Uribe fuels his claims of politically motivated conviction

A court finds that the judge who sentenced the former Colombian president erred in ordering his house arrest

The case for which former Colombian president Álvaro Uribe Vélez, 73, was sentenced to 12 years in prison continues to shake the country. This past Monday, two magistrates from the Superior Court of Bogotá annulled part of the ruling in which, two weeks earlier, a judge in the same city had determined that the founder of the Democratic Center political party was responsible for the crimes of bribery in judicial proceedings and procedural fraud.

The magistrates found that Judge Sandra Heredia violated the right-wing leader’s fundamental rights by ruling that he should serve his sentence without waiting for a second-instance review — a decision that is normally reserved for exceptional cases.

This supports the argument of Uribe, his lawyers, and his allies that the judge acted with political motivations. “The lack of impartiality of Judge 44 and the lack of guarantees suffered by Álvaro Uribe in the process against him have been demonstrated,” posted Uribe’s congressional ally Andrés Forero, one of many public statements supporting this argument.

Tuesday’s decision, another first-instance ruling that can be appealed or even reviewed by the Constitutional Court, occurs in a context familiar to Colombians: the debate over a tutela action, a legal procedure intended to safeguard fundamental rights in cases where there is no other effective way to protect them.

Uribe’s defense, led by criminal lawyer Jaime Granados, chose this fast, simple, and very popular route — in 2024, more than 950,000 tutelas were filed — to secure Uribe’s release. His team focused on challenging Heredia’s reasoning behind the argument that Uribe should begin serving his sentence prior to an appellate review — one of the most controversial parts of the order — arguing that it was so precarious that it should be lifted immediately while the court fully reviewed the tutela request.

Magistrate Leonel Rogeles, in charge of processing the petition, initially denied the request. “At this time, no irregularities are evident that are significant enough to establish a significant impact on fundamental rights,” he wrote in an order that led to the former president’s preventive detention.

Meanwhile, Uribe’s political base launched a two-pronged media and political campaign. On one hand, they accused Judge Heredia — and the Colombian judiciary in general — of being part of a lawfare strategy (instrumentalizing the justice system).

“The only explanation for a ruling against is that it’s due to lawfare,” Granados told this newspaper a few weeks earlier.

“Politics has prevailed over the law to convict me,” Uribe declared.

“This isn’t a ruling, it’s revenge. It’s not a sentence, it’s an attack. It’s not justice, it’s fear,” Senator and presidential candidate Paloma Valencia posted on X.

She was seconded by María Fernanda Cabal, her colleague in Congress and in the campaign. “It will be a driving force in the fight for a justice system that is never exploited to judicialize politics,” she said of the ruling.

Even U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio joined in: “The weaponization of Colombia’s judicial branch by radical judges has now set a worrisome precedent,” he shared on X.

This narrative gained renewed traction on Tuesday, as the tutela argued that Heredia’s decision acted “to the detriment of [Uribe’s] fundamental right to individual liberty.”

This story carries strong emotional weight, forming the second prong of Uribe’s response to the conviction. Three days after the initial tutela denial, with the politician formally confined to his country home near Medellín, thousands of people marched on National Day to protest the conviction and detention.

“More than for Álvaro Uribe’s innocence, I march so that the fight against the narco-socialism they want to impose on us can continue freely,” said Jerónimo Uribe, the former president’s son, in the streets of the country’s second-largest city.

It’s a forward-looking message, oriented toward what lies ahead, which was exactly what the former president emphasized in his first reaction following Tuesday’s ruling. “Thank God, thank you to so many compatriots for their expressions of solidarity. Every minute of my freedom I will dedicate to the freedom of Colombia,” he wrote in X.

Gracias a Dios, gracias a tantos compatriotas por sus expresiones de solidaridad.

— Álvaro Uribe Vélez (@AlvaroUribeVel) August 20, 2025

Cada minuto de mi libertad lo dedicaré a la libertad de Colombia.

It echoes what his son had said on the streets of his city, or the call from his party for those mobilizations: “We will march for Álvaro Uribe Vélez, for democracy and freedoms in Colombia. Also to tell the country that there is little time left: we are just over a year away from ending the dark night.”

It is a call to focus on the 2026 legislative and presidential elections, framing the effort under the banner of political persecution. This is particularly resonant for a party that was founded in 2013 as a right-wing political uprising against the government of Juan Manuel Santos. A key part of the party’s lore is the (unproven) claim that it was defrauded in the 2014 election, when the then-president lost the first round but won the second against the Uribista candidate Óscar Iván Zuluaga.

What’s more, it is a party that last week buried its senator and presidential hopeful Miguel Uribe Turbay, who was assassinated in an attack ordered by perpetrators who have yet to be identified.

Throughout the protracted legal process that began against Uribe in February 2018, he had already been detained in 2020 while serving as a senator, the Bogotá Tribunal had already examined tutelas and ruled both for and against him, and national elections had taken place — both won by the right in 2018 and by the left in 2022

What has not happened until now are such abrupt twists at a moment when Uribe needs to select a candidate, nor outcomes that are so decisive for the distribution of power in elections just months away. Nor have there been such tight deadlines: only two months remain before the case could be closed due to the statute of limitations — a resolution that would relieve Uribe of a headache but would not give him the political momentum of a full acquittal or the impact of a confirmed conviction.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.