China’s ‘ideological czar’ who predicted America’s division in the Trump era

Wang Huning, the fourth-ranking member of the Communist Party, traveled to the United States in 1988 and compiled his reflections in a prophetic book titled ‘America Against America’

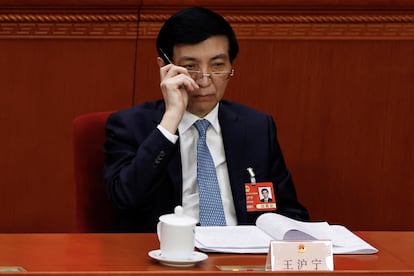

On October 23, 2022, seven men entered the golden hall of the Great Hall of the People in Tiananmen Square through a massive gold-adorned door. They slowly made their way to the stage, led by Xi Jinping, and lined up in strict hierarchical order around the leader. This was the public unveiling of the new Politburo Standing Committee — the core of power within the Chinese Communist Party. Their placement hinted at their importance. In fourth position, behind Xi and the future premier and president of the National People’s Congress (China’s legislature), stood Wang Huning — a thin man with an impassive face, jet-black dyed hair, and the air of a professor: China’s ideological czar.

Wang, 69, is behind many of the theories and slogans that shape China’s current system. He is one of Xi’s trusted allies; he heads the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the top advisory body; and some refer to him as “China’s Kissinger.” In the late 1980s, he spent six months traveling across the United States. He compiled his experiences in a book published in 1991, in which he reflected on the fractures within the world’s leading power. Its title had a prophetic tone, hinting at today’s era of division: America Against America.

The book — which has been out of print for years — analyzes the contradictions and fractures within U.S. society. It became a true phenomenon in China in 2021, after the storming of the U.S. Capitol by a mob seeking to keep Donald Trump in power. It offers the perspective of a young political scientist from a Marxist-Leninist country newly immersed in the capitalist world — and it contains intriguing insight into how today’s Chinese leadership views the United States.

Wang — who was the youngest associate professor in the Political Science Department at the prestigious Fudan University in Shanghai — was 33 years old when he arrived in the U.S. It was a time of openness and exchange. He was part of a delegation from the Chinese Political Science Society, and the trip was organized by colleagues from the American Political Science Association.

It was the twilight of the Cold War. The U.S. was the undisputed global power. Francis Fukuyama’s supposed “end of history” was approaching. George H. W. Bush was about to win the election. The West and capitalism were at their peak. Wang chose the country as his object of study. He set out to unravel the “American phenomenon,” approaching it “as an observer rather than a researcher,” as he explains in the opening pages. The title, he writes, refers to the “positive” and “negative” forces that coexist in the country. His aim was to go beyond both the idealized view of a “rich paradise” and the grim portrayal of a “dictatorship of the bourgeoisie.”

He visits Chinatown, universities, factories, and plantations, the Coca-Cola headquarters; analyzes lobbying and the dynamics of economic power groups; is fascinated by how phones, cars, credit cards, and computers permeate daily life; describes the ravages of drug abuse; reflects on the sexual revolution and the clash between feminism and traditional values; observes Bush’s campaign and the electoral debates; walks through neighborhoods full of sex workers and squares filled with homeless people; questions the origins of the “American spirit”; visits museums, passes through tiny towns in Ohio, and interviews dozens of people from all walks of life — from farmers to politicians.

Chapter by chapter, the author weaves his observations with questions, always with his own country in the background. One can already sense China’s drive to become a leading global power: “The economic success and technological progress achieved by the United States in this century are there for all to see, and no country in the world today has yet surpassed it,” he writes. “How can China’s economic modernization be achieved? The fundamental question is whether the process of economic modernization can be completed under public ownership.”

The “Chinese dream”

It’s no surprise that Wang, several decades later, would be the architect of the “Chinese Dream” — a slogan echoing the American Dream and frequently repeated by Xi during his early years in office.

During his trip, Wang also glimpses some of the fault lines that would emerge in the future. He notes how the U.S. is flooded with foreign-made goods (a precursor to the trade imbalance behind Trump’s trade war); he observes the offshoring of factories and warns about the impact of factory closures on industry and unemployment: “The two forces of free trade and protectionism have always clashed,” he writes.

In comparing the United States — which he sees as a nation in decline — with Japan — then a rising Eastern power — he sketches out key ideas that help explain China’s current model: “The American system, generally based on individualism, hedonism, and democracy, is clearly losing to a system rooted in collectivism, selflessness, and authoritarianism.”

Ren Xiao, a former student of Wang at Fudan and now a professor at the Institute of International Studies at the same university, believes the title of the book was spot on. It reflects “the deep internal contradictions” of the United States, he says over the phone. “Many years later,” he adds, referring to the storming of the Capitol, that clash between two Americas became evident. “That speaks to his long-term vision.”

Wang, the former student adds, stood out for being young, extremely hardworking, and highly educated. He supervised Ren’s thesis and, during graduate studies, taught a course on classic texts of Western political thought. They studied everything from the ancient Greeks to modern thinkers like Montesquieu, Locke, and Rousseau. He would ask students to read a full work each week — a pace they often couldn’t keep up with. “He helped us a lot.”

Wang soon caught the attention of the Chinese government as a proponent of neo-authoritarianism, a political school of thought described by Trivium China analysts in a newsletter about Wang as “a precursor to the state-led capitalist model in vogue under Xi Jinping.”

He built his career within the Central Policy Research Office, a party think tank he led for nearly two decades. He has been an advisor to China’s last three leaders: Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao, and now Xi Jinping, under whom his influence has soared.

In 2017, he was appointed to the Politburo Standing Committee for the first time (then in fifth position) and was put in charge of propaganda and ideology. Today, in addition to chairing the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, he oversees Taiwan affairs and religious issues — two of the country’s most persistent challenges.

His thinking has shaped initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative (China’s massive global infrastructure and investment strategy), and “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” the president’s official ideology — enshrined in the Constitution alongside Mao Zedong’s theories, according to the Hong Kong newspaper South China Morning Post.

On his trip to the United States, he already sensed the doubts and anxieties that would plague the North American nation in the face of the rise of a new power: “It will be then that Americans will truly reflect on their politics, their economy, and their culture.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.