Emojis, slang, and hashtags: The Jalisco New Generation and Sinaloa Cartels attract young people on TikTok

A study by the Colegio de México reveals that the CJNG is the most active in using social media to recruit adolescents

“Looking for people for the 4 letters. Age doesn’t matter, teach them my race [sic],” reads one text, accompanied by a small yellow face emulating a military salute. This message is superimposed over a video showing the inside of a car, which is part of a convoy that appears to be patrolling a vacant lot at night. Various examples and variations of this production can be found on the social media platform TikTok. This content is created and disseminated by the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) or the Sinaloa Cartel, which use colloquial language, slang, music, hashtags, and emojis to communicate with young people to attract them to their ranks, according to a study by the Violence and Peace Seminar at the Colegio de México.

The research “New Frontiers in Digital Recruitment. Organized Crime Recruitment Strategies on TikTok,” conducted by the Laboratory of Hatred and Harmony in collaboration with the Civic A.I. Lab at Northeastern University, documents more than 100 active accounts in Mexico and reaffirms what has been reported in recent weeks: how cartels offer fraudulent job opportunities through platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and TikTok.

The Teuchitlán case — the ranch discovered by relatives of missing persons in March in the center of the country — has shed light on this phenomenon, about which little was known until recently. “Multiple disappearances of young people in the Valley of Mexico have already been linked to this type of situation. They took a bus to Jalisco to go to work and, shortly after, were never heard from again,” the document states.

According to the results of this preliminary report, the Jalisco New Generation Cartel leads the use of TikTok as a recruitment and propaganda channel. Of the 100 accounts studied, 54% were linked to this criminal organization. The Sinaloa Cartel and the factions warring for control of the organization — Los Chapitos and La Mayiza — and the Northeast Cartel each represented just over 5% of the total.

The report explains that a digital ethnography was first constructed to identify words, hashtags, and symbols shared in recruitment posts on TikTok. This database was sent to Northeastern’s Civic A.I. Lab so that, through an interface, they could assist in gathering precise information about the accounts’ activity and their engagement metrics.

“Many of the accounts we analyzed were only active for a short period of time, either because they were shut down by the platform or deleted by the users themselves [...] In terms of security, some of the accounts we identified belonged to minors. [...] The accounts in our sample made explicit references to organized crime through the sharing of expressions, symbols, and songs,” explains another excerpt from the document.

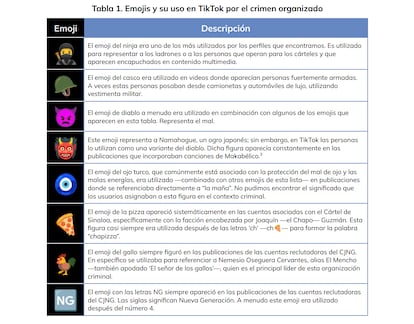

Emojis that hide references to drug trafficking

The investigation mentions one of the most important elements that helped identify drug-related content was the systematic use of emojis, a digital icon used in electronic communications to represent an emotion, an object, or an idea, which made references to criminal life and its characteristics.

Some examples cited in the report include the ninja emoji (🥷🏼), used to represent people who work for cartels or recruit hitmen. Another is the pizza slice emoji, which appears frequently on accounts associated with the Sinaloa Cartel, specifically the faction of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán’s sons. This emoji was almost always preceded by the letters “ch” (ch🍕) to form the word “chapizza,” a reference to their nickname.

On the other hand, the rooster emoji has always appeared in content linked to CJNG recruiting accounts. The symbol represents Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes, alias “El Mencho” — also nicknamed “El Señor de los Gallos (Lord of the Roosters) — the cartel’s top leader. Digital icons with the letters NG also referenced this criminal organization, which stands for New Generation, often used after the number 4, due to the letters that abbreviate the organization’s name.

“TikTok isn't just entertainment. It's also a space where organized crime builds identity, community, and promises of belonging. Of the 100 accounts in our sample, 47% engaged in explicit recruitment activities. The second most common type of account was propaganda [31%], that is, accounts that actively promoted the name of a criminal organization through music and other symbols,” the document states.

This modus operandi employed by several criminal organizations was confirmed during the Mexican government’s morning press conference on March 24, when Secretary of Security Omar García Harfuch presented a report on the Teuchitlán case. There, he identified José Gregorio, alias Commander Lastra, as one of the main people responsible for the CJNG’s recruitment activities in Jalisco, Nayarit, and Zacatecas. In this same report, the authorities announced that 39 TikTok accounts that recruited people for this cartel had been shut down.

The situation is worrying. The most recent assessments attest to this. A national analysis on the recruitment of children and adolescents by organized crime groups conducted by the Ministry of the Interior in 2021 — but publicly revived after the discovery of the ranch in Teuchitlán — reveals that seven out of 10 recruits at that age grew up in high-crime environments. The report also explains how organized crime groups employ minors, first to work as messengers, and then to climb a pyramid structure that culminates in the training of hitmen or other positions that involve very high levels of violence.

“TikTok has made it easier for organized crime to use this digital space to construct new identities that are expressed through shared images, emojis, hashtags, and songs. In this way, organized crime manages to permeate Mexican youth, with the promise of belonging to a group where they will be accepted and where they can receive better opportunities for their future development,” the document states.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.