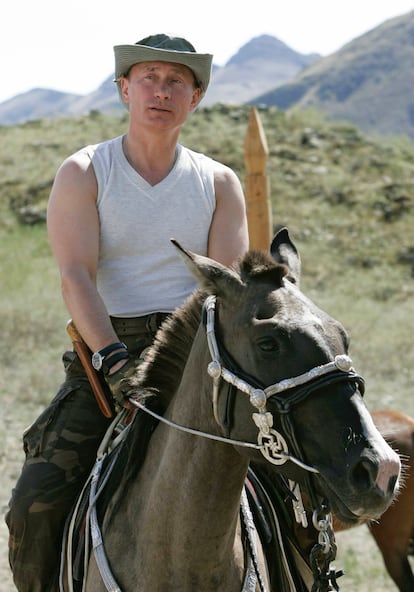

Putin marks 25 years in the Kremlin with Ukraine war and internal authoritarianism at fever pitch

The hardening of the regime has been a gradual process in which the Russian leader counted on the passive loyalty of the population in exchange for a stability that his ambition has broken

The Putin era turns a quarter of a century old on Tuesday. Twenty-five years since December 31, 1999, when an exhausted Boris Yeltsin resigned and handed over the interim presidency, all the resources of the state, and the support of his oligarchs to a heavyweight of Russian espionage, Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin. A regime built with the passive support of a population who only wanted peace after the turbulent 1990s, but in which today the fear of being arrested reigns supreme. A nation to which Putin promised peace, but to which today hundreds of thousands of dead and wounded are returning from his war in Ukraine, the most costly in Europe since the Second World War.

Putin was an unknown figure when Yeltsin appointed him prime minister months earlier, in August 1999. The offensive he launched a month later against Chechnya boosted his popularity. The reason for the war was a series of explosions in residential buildings that ended when the local police in Ryazan discovered another basement full of explosives that, as it turned out, belonged to the Federal Security Service (FSB), the successor agency to the KGB. Nikolai Patrushev, head of Russian intelligence at the time and a close adviser to Putin, said that it was “a training session.” The incident was never investigated by parliament.

“I remember us as free / but someone drank the poison / and the howling of hungry wolves / became the silence of the lambs,” sings the band Nogu Svelo!, now in exile. The hardening of Putinism was a gradual process with a tacit pact between the Kremlin and the Russian people: if you don’t meddle in politics, you will have a more or less peaceful life.

This transformation was supported for many years by the West. The first decree signed by Putin upon coming to power prohibited the prosecution of Boris Yeltsin and his entourage, who were nicknamed “The Family.”

The next step was to censor a joke. The Kremlin put pressure on the opposition channel NTV, owned by Vladimir Gusinsky, to cease the broadcast of the satirical puppet show Kukli. Putin was portrayed as “Little Zaches,” an evil elf who magically appeared to the people as a beautiful young man. Gusinsky ended up in exile and NTV in the hands of Gazprom, the state-run energy giant.

A quarter of a century later, the regime’s internal repression has surpassed the heavy-handedness of any post-Stalin Soviet leader. The independent outlet Proekt has identified at least 11,442 people tried under criminal cases and 116,000 under administrative proceedings for expressing their opinions or participating in demonstrations in Putin’s penultimate term in office (2018-2023). Of these, 5,613 citizens were tried for “extremism” or “discrediting the authorities,” compared to 3,234 similar cases recorded in the USSR from 1962 to 1985 under autocrats such as Leonid Brezhnev and Yuri Andropov.

“Our previous generation of politicians destroyed their own country in the hope that Russia would become part of the so-called civilized world,” Putin said a couple of weeks ago. But the elite of Putinism is made up of former members of Yeltsin’s bureau.

Putin headed the FSB in 1998; Sergey Kiriyenko, now in charge of the inner workings of the administration, was prime minister when the dramatic 1998 ruble crisis erupted; former defense minister Sergei Shoigu propelled Putin to his first election thanks to his popularity as minister of emergency situations; and the architect of Russian foreign diplomacy in the 21st century, Sergey Lavrov, was Russia’s permanent representative to the United Nations in the 1990s.

The key moments

Riddle think tank director Anton Barbashin, speaking by phone, emphasizes the date of September 24, 2011 as a very important milestone in the Putin era. It was the day when then-president Dmitry Medvedev announced the re-nomination of Putin after the two had rotated one legislative term to get around the constitutional limit of two terms.

“That determined 2014 — the illegal annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas — and 2022, the final invasion of Ukraine,” says Barbashin. “Putin became convinced that he had to return [to power] and we saw the strengthening of authoritarianism.”

Intigam Mamedov, an Eastern Europe expert and researcher at Northumbria University, points in another telephone conversation to Putin’s speech at the 2007 Munich Security Conference, when he said a unipolar world order was unacceptable and accused NATO of reducing mutual trust in its ongoing eastward expansion.

“That intervention was very popular in Russia; it was perceived as the return of our sovereign word to the international stage,” Intigam says.

The expert also points to the constitutional reform in 2020 as a key milestone: “The Kremlin’s great self-confidence was evident when the Basic Law was amended and the president’s mandates were restored. It suddenly became clear that in order to carry out such a serious political act, the authorities did not need any sophistication.”

That constitutional reform cleared the way for Putin to remain president until 2036 if he wishes.

Two fronts

“The Putin regime is waging war on two fronts: external and internal. Even if the hot phase of the war ends, the suppression of internal civil society will not. The system will remain the same, or become even harsher,” predicts journalist Andrey Kolesnikov, who has been declared a foreign agent by the Russian authorities.

A survey by the independent Levada polling center showed that in 2023 about a fifth of Russians “aggressively and actively” supported Putin, war, and repression, while about the same proportion opposed it. In the middle ground, a huge mass of people who are carried away by the Kremlin.

“In an attempt to explain the terrible and inexplicable, they have convinced themselves with the arguments of Putin himself and television propaganda,” Kolesnikov said in an email exchange. “They adopt a fetal position: I don’t want to see or hear anything. But this brings with it punishments and moral doubts.”

In fact, Russian opinion is very fickle: another poll from 2021, before the war, showed that 55% of the country considered relations with Ukraine to be good, while only 31% thought they were bad.

The Kremlin is trying to avoid a new forced mobilization at all costs because it would break the current social pact: no one goes to the front unless it is for money or of their own free will, but in return they must show absolute loyalty to the authorities. But the war drags on.

“We have a universal Gleichschaltung — forced or voluntary submission to the formal and informal rules of the regime. Passive conformists, their learned indifference, is the basis of the Putin system. But now they are sometimes required to join the squad of active conformists,” Kolesnikov stresses, calling on the West to be more understanding toward the opposition because it is physically impossible to protest in Russia. “We should not create any further obstacles with measures that would further consolidate the conformist majority around Putin,” Kolesnikov adds.

Mamedov agrees that support for Putin “is broad, but at the same time it can be fragile if it is based on simple conformism and loyalty to whoever is in power.” The expert believes that Putinism has failed to establish itself as an ideology. “It has not managed to create an image of the future. Instead of acting to achieve some goals in the future — as was done with communism, for example — Putinism bases its current policies on the past, nostalgia, and historical traumas.”

The philosopher Zygmunt Bauman wrote about so-called retropia, the dream of an ideal future state with nostalgia for an unreal past. The entire rhetoric of Putinism revolves around past imperial glory and “the defense of traditional values” against the “decadent” liberal West. Putin, who called the demise of the USSR “the greatest tragedy of the 20th century,” characterizes Russia as a “civilizational state.”

However, the foundations of the regime are shaking. In an analysis published by the Carnegie Center, political scientist Tatiana Stanovaya says that the country is going through a phase of “wild Putinism,” a trend in which clashes between the different Russian factions are becoming more and more open because Putin has grown tired of mediating internal disputes and only thinks about “war and the clash of civilizations.”

The expert warns that the law “has become not worth the paper it is written on” in Russia in recent years, and a very unstable scenario is opening up. “Imprisonments, compromising evidence and attacks will become the main way of survival, often under conservative and anti-Western slogans,” she predicts.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.