Drones, tension and votes in plain sight in Russian elections without a rival for Putin

Residents of the Russian border city of Belgorod report an unprecedented intensity of attacks attributed to Ukraine. In Kursk, support for the president is resounding on the first election day

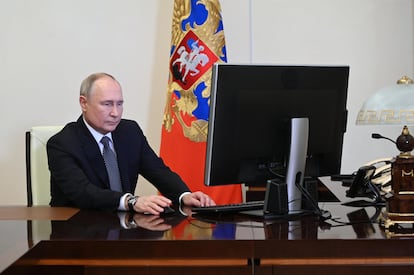

The presidential elections started this Friday in Russia with widespread distrust in the West about the reliability of the result. The elections, without any real opposition, without international observers and with an opaque electronic voting system for the first time in a presidential election, will perpetuate Vladimir Putin in power at least until 2030. The voting process, which will last until this Sunday, has 4.7 million potential online voters, of which two million are estimated to have already deposited their electronic ballot. One of them was Putin himself, who voted from the computer in his office at the Novo-Ogaryovo residence, on the outskirts of Moscow. Taking into account the entire vote—in the ballot box and online—the authorities estimate that 35% of the more than 112 million voters have already cast it.

One of the biggest disruptions of the day was recorded in Belgorod, just 50 miles from the Ukrainian city of Kharkiv and where the voting day began with the wailing of sirens. At least one person died in a wave of attacks attributed to Ukraine and anti-aircraft fire “never seen in these years of war,” according to several residents of the Russian town. In this context, its inhabitants could only think about the Ukrainian attacks. “You can’t imagine how heated things have become here,” said Evguenia, a woman in her 40s who lives in the city of Belgorod, on Thursday night. The woman was riddled with doubts. “I don’t dare leave the house. I don’t know what to do, leave or not. “When will this end?” she lamented in a telephone conversation.

Faced with the agitation in Belgorod, there was a truce in the neighboring city of Kursk, also under attack these days. “Let’s knock on wood,” exclaimed bystanders at School Number 4 on Dmítrova Street, while an incessant trickle of people, almost all of them older, voted throughout the morning. “I stand with my president, Vladimir Vladimirovich (Putin),” was a phrase repeated by several of the voters. Kursk (population 434,000) is one of the 28 Russian administrative entities where controversial online voting has been enabled. According to the calculations of one of the voting stations, around 10% of its 773 registered voters will select this option. Added to these are another 20 people who, due to mobility problems, will receive a house call so they can vote.

According to the independent organization Golos, extending these elections for several days makes it easier for the administration and many companies to put pressure on their employees to use the opaque online voting system, about whose trustworthiness there are doubts.

The spokesman for the Russian president, Dmitri Peskov, avoided commenting on the attacks in the border area and delegated this issue to the Russian Ministry of Defense. On Friday, another refinery in the Kaluga region, south of Moscow, joined the list of Russian energy facilities hit by drones in recent days.

On a day with strong security measures, several people were arrested for pouring liquids, including ink, into ballot boxes. The Central Election Commission indicated that all the “attackers” were arrested and that a criminal case will be opened against them. According to authorities, at least five voting centers located in Moscow, Voronezh and Rostov recorded incidents of this type. In addition, the opposition Civic Initiative party and its candidate, Boris Nadezhdin, banned from the elections, were victims of incidents. Its headquarters in Kazan was attacked by observers from the Public Chamber, a civil consultation body, and a volunteer was detained in Khanty-Mansiisk province while conducting a survey outside the polling station.

Instead, calm reigned at the entrance to the Kursk school, guarded by several police officers. At first glance, these seem like a normal election. In the hall, a screen shows the photos of the four presidential candidates with their resumes and the assets they have declared. The candidates of the Communist Party, the Liberal-Democratic Party and New People present endless texts. The text for Putin, however, is summarized in a few lines and highlights that he is “president of the Russian Federation.” Behind it, the figure of President Putin is magnified in a mural with the motto “Russia, our great power!”, another photo of the Russian leader and a map and the country’s flag.

The electoral college is divided into two voting points, numbers 125 and 126. In each of them there is a screen where voters can mark their candidate with a cross on a huge ballot. It is deposited in a glass ballot box without any envelope to cover the election choice, as is the custom in countries like Spain. In fact, with simple backlighting it is possible to see the vote marked on the other side of the paper.

“Our ballot boxes are transparent so that you can check which ballots there are. If the voter does not want his vote to be seen, he can fold the ballot,” says the head of the electoral commission at that voting station, Roman Filippov. In this polling place there are only observers from United Russia, the party that is nominating Putin as president, although they expect the presence of representatives from other official parties on one of the three days that the elections will last.

Almost all the observers of Russia’s first voting day refused to speak, except for one young woman, Galina Ivanovna, who joined out of tradition. “I just turned 18 years old. We have the habit of going to the elections together as a family,” she says. Russian electoral committees are made up entirely of volunteers, most of them nominated by the parties.

The start of the elections coincides with the complaint by an independent Russian media, Sirena, that some polling stations in the Kursk region use pens with ink that can disappear with the heat of a lighter. “I can’t say, it doesn’t happen here. Maybe it is some kind of provocation,” replies the person in charge of the voting station. “At the moment everything is going well, without incidents.”

After casting their ballots, voters receive a certificate in which the authorities thank them for having participated despite the tension experienced with the drones. Unlike other regions (Moscow has a program of “a million rewards” for going to vote, including discounts on shows) in Kursk there is reportedly no compensation.

Open support for the president

It is working hours and practically everyone who goes to the polls is older, although in many regions it is common for civil servants and some company personnel to also receive permission to go vote. Support for Putin here is resounding. “Why hide it? “I voted for Vladimir Putin, a great president,” declares Alexánder, a pensioner from School Number 4, upon leaving the station. “I was sure that he would go to the end [in the war against Ukraine],” he adds with a smile.

The Ukrainian attacks these days are something new for Kursk, but for Alexander the culprit is clear and it is Kyiv. “We are perfectly fine, we are not afraid. It is necessary to respond to Zelenskiy, that drug addict,” he adds.

An older couple also comes to vote, but refuses to comment on the Russian leader. “Each Russian makes his choice about who he wants in power, that is an absolutely personal matter,” says the man.

In any case, only people loyal to Putin are likely to speak openly in these elections. “They are not a special election,” says Anna, a middle-aged woman whose daughter is now a journalist for a Kremlin channel. “I think we should support our president.” Asked about the attacks experienced these days, she responds like many other Russians that only the Kremlin can have answers because citizens do not participate in politics. “As a citizen I can’t say if something is bad. I only admire my president and we must support him,” she insists before resorting to a saying: “In Russia we usually say that we do not change horses in the middle of the crossing.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.