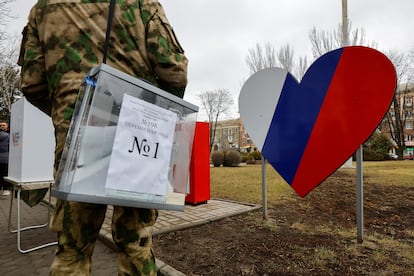

Russia goes to the polls in elections tailored to guarantee Putin power until 2030

The president’s three supposed rivals all support the Kremlin and the vote, which will be held from Friday to Sunday without international observers, uses an opaque electronic system

The presidential election being held in Russia between Friday and Sunday presents a bleak outlook for the electorate: never before has Vladimir Putin, who will extend his mandate until 2030, faced so few rival candidates, and his three supposed opponents unconditionally support the Kremlin. Moreover, this will be the first presidential election with the opaque internet voting system, and observers from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) will not be present. The Kremlin’s aim is to turn the election into a plebiscite, a demonstration of mass support, with which Putin can justify the harsh measures he will adopt in the future.

Of the 25 political parties permitted in Russia only eight, including the president’s own, have dared to present a candidate. The presidential filter has been inflexible. Only three formations loyal to power — the Communist Party, the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia and New People — made the cut. For its part, the largest party in the country, United Russia, did not nominate anyone from within its organization, but unanimously backed the candidacy of the “independent” Putin.

The president has shored up his power in the six years since the previous presidential election in 2018. Through a 2020 constitutional reform he zeroed out all his accumulated mandates since 2000 and can now remain in the Kremlin until 2036. Laws enacted this legislature, and prison cells, have removed any candidate the presidential administration deems dangerous to its plans from the running.

“And yet, the Kremlin is afraid to register a liberal candidate,” Stanislav Andreichuk, a board member of Golos, Russia’s largest independent election transparency organization, tells this newspaper. “It is the smallest number of presidential candidates in the entire history of Russian elections, only equaled by 2008, when Dmitry Medvedev took turns with Putin,” he notes.

The visible heads of the Russian opposition are in jail, in exile, or dead. One of the most prominent dissident leaders, Alexei Navalny, died suddenly in prison a month before the elections. His funeral drew tens of thousands of Russians despite the Kremlin’s boycott and the arrests of hundreds of peaceful protesters following his death.

Candidates vetoed

Without reference points, the section of the population critical of the government grasps at any straw to show its discontent. As such, Russia’s Central Election Commission has vetoed two candidates who mobilized huge lines of people willing to sign to endorse their candidacy. Political scientist Boris Nadezhdin — supposedly an opponent of the Ukraine war although he participates in the Kremlin’s propaganda media — collected some 300,000 signatures, but the electoral board annulled enough of them to prohibit his participation. Something similar happened to journalist Yekaterina Duntsova, who was arrested when she was presenting a new party in January.

The opposition Yábloko party turned 30 in October. It has not been able to present a candidate, but still maintains its struggle within the system, in town halls and regional assemblies, with the slogan “for peace and freedom.” “Classical politics — fighting against the decisions of the authorities in elections — is forbidden, it is practically impossible. But it is possible to fight for ideas, for people’s souls,” the chairman of the formation, Nikolay Rybakov, tells EL PAÍS.

“With our activity we show that there is a significant number of Russians who support peace and freedom, and it is important for the hope for a better, peaceful future to be preserved. If this is not done now, it cannot be done in the future,” he adds.

This will be the second Russian election — and the first presidential election — since 1993 to be held without an OSCE observer mission. As in the pseudo-referendums for the annexation of the occupied Ukrainian territories in 2022, the Kremlin will bring its own “international observers,” some of them Spanish citizens, to present the idea that they are clean and fair.

Internet voting under the watchful eye of the boss

In addition, this time the authorities have implemented a controversial electronic voting system at 27 electoral points — most of them problematic areas for Putin — including his two cosmopolitan metropolises, Moscow and St. Petersburg. During the 2021 local elections, United Russia was losing in several districts of the capital as the physical ballots were being counted. In the early hours of the morning, after “scrutiny” of the online votes that lasted over 15 hours, the two million electronic votes that fell into the system gave a landslide victory to the party of which the president is de facto leader.

Golos denounces that it is an opaque system because only the final figures are visible on a screen, but access to the code is restricted to the Kremlin’s computer scientists. Moreover, via this method, it is easier to check whether a citizen has voted as the authorities wish.

“If your boss requires you to vote, but you do it with a ballot at a traditional polling station, no one can check who you voted for. With internet voting we don’t have that guarantee,” Andreichuk says. In addition, most electronic votes come into the system on Friday mornings, “just when people are at work with the bosses behind their backs.”

The other method the Kremlin employs to force the population to vote is an application devised by United Russia (GEO-SMS) for public employees, to certify that they went to the ballot box that corresponds to them through the geolocation on their cell phones. This coercion is unconstitutional, because not voting is also a political choice.

Another controversial aspect of the election is that it is being held in the occupied territories, including Crimea. The international community, including China, does not recognize its annexation, a large part of the population has fled their homes and fear is present in the form of bombs and Russian security forces. “Moreover, the organization of elections in these territories contradicts Russian legislation,” notes Andreichuk, who gives as an example that there voters can go to the polls without a Russian passport, using a Ukrainian one or those issued by the “people’s republics” of Donetsk and Luhansk. “The election commissions in those areas have been formed without party representatives and there are practically no observers,” he adds.

The European Platform for Democratic Elections (EPDE) has called on the international community not to recognize the polls taking place on occupied land. “Five million voters from these territories are forced to participate in the elections, approximately 4.8% of the total number of voters”, emphasizes the organization. It is a very high percentage: by way of comparison, the Russian Central Election Commission vetoes candidates if it considers that 5% of the signatures they present to run for office contain — in its eyes — some kind of irregularity.

The electoral investigator Sergey Shpilkin, who has been declared a foreign agent by the Kremlin, in 2008 published a system to estimate the number of fraudulent votes in the Russian elections. According to his calculations, in all the elections held since then, including legislative ballots, there were between 10 and 15 million irregular votes, although in 2020, because of the restrictions applied due to the coronavirus pandemic, this figure soared to over 25 million.

Also striking is the contradiction between the authorities’ efforts to promote a high turnout in Putin’s “plebiscite” — both with remote control systems and millions of free gifts and free tickets to events for turning out to vote — while encouraging disinterest in the candidates.

The Russian president has not attended any election debates, where the focus was on the West and not the Kremlin, and as the elections have approached federal TV stations have devoted minimal space to his “rivals.” According to Golos, the Communist Party candidate received 17 minutes in total from the six national channels over a full week, while the other two candidates got less than 10 minutes. Putin, the eternal president, appeared exultant at all hours on the screens of Russian homes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.