Thousands of Syrians search for relatives in the ‘human slaughterhouse,’ the prison that is a symbol of Assad’s repression: ‘He could be dying underground’

The Sednaya military prison is filled with desperate people seeking news of their loved ones, clinging to the rumor that thousands of prisoners remain in underground cells

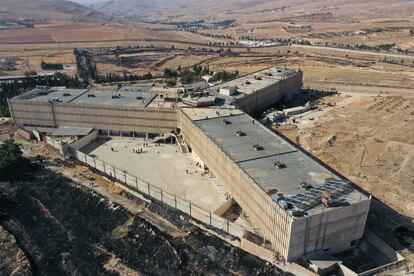

The image, with the rawness of when nothing is staged, is chilling. Thousands of Syrians walk in a hurry uphill for miles (traffic jams prevent them from getting close) to reach Sednaya as soon as possible, the military prison nicknamed “the human slaughterhouse” where the regime of Bashar al-Assad killed thousands of people and where only now, after the fall of the dictatorship, can they arrive en masse, desperately seeking news of their loved ones, clinging to the rumor that there are still thousands of prisoners in underground cells.

Women with tears in their eyes, families with folders with the names and ID numbers of loved ones they haven’t heard from for years, and a desperate question from those going up to those going back down: “Have you found them?” A kind of procession towards the horror of a prison where the men dig with whatever they have — even with an iron bar — in search of a supposed secret entrance to the basement, and where they show a cell where prisoners were kept (alive or dead, they say) and the ropes used to torture them that their jailers hastily left behind.

Sitting on the dusty ground, an elderly woman shouts at the rebel fighters, who opened the prison gates on Sunday to free the inmates and who are now climbing in with Kalashnikov rifles slung on their shoulders: “Come on up, come on up! For what? You came years too late!”

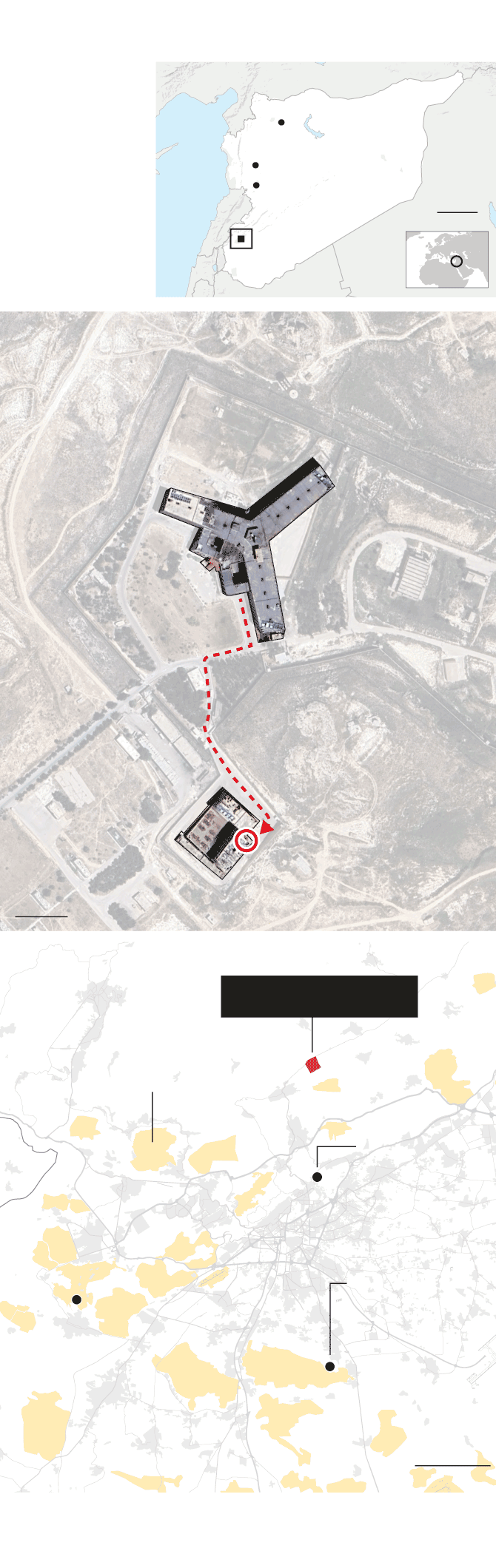

The horror of Sednaya prison

Aleppo

Hama

SYRIA

Homs

100 km

Damascus

Prisoners were moved at dawn from the red building to the white building to be executed.

Red building

White building

Execution room

(in the basement)

50 m

Sednaya prison

Military

zones

Tishreen

military

hospital

Damascus

Najha

(several

grave sites)

Qatana

(graves

in military

zone)

10 km

Source: Amnesty international, OSM and GoogleMaps.

R. SILVA - N. CATALÁN / EL PAÍS

The horror of Sednaya prison

Aleppo

Hama

SYRIA

Homs

100 km

Damascus

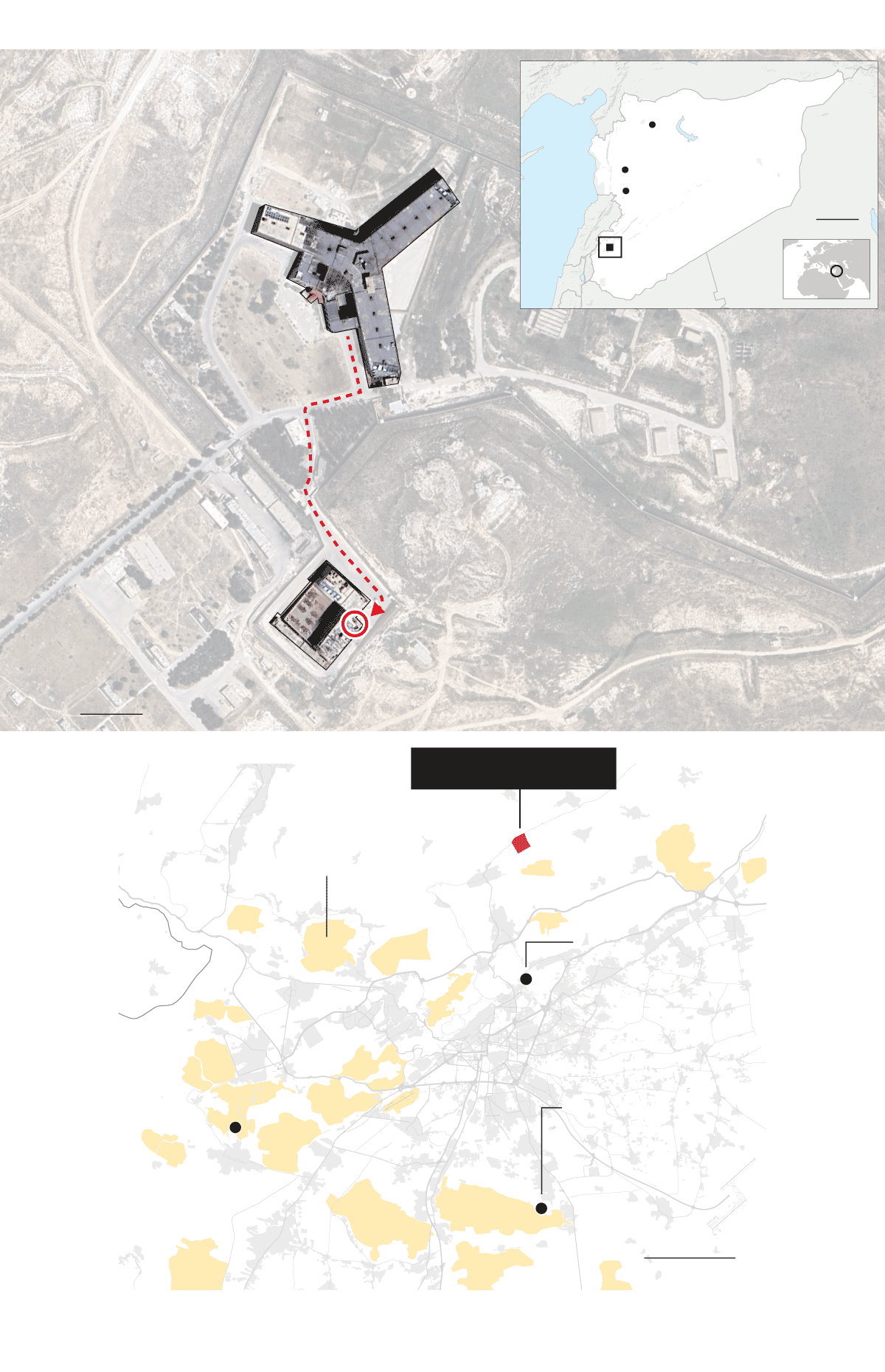

Prisoners were moved at dawn from the red building to the white building to be executed.

Red building

White building

Execution room

(in the basement)

50 m

Sednaya prison

Military

zones

Tishreen

military

hospital

Damascus

Najha

(several

grave sites)

Qatana

(graves

in military

zone)

10 km

Source: Amnesty international, OSM and GoogleMaps.

R. SILVA - N. CATALÁN / EL PAÍS

The horror of Sednaya prison

Prisoners were moved at dawn from the red building to the white building to be executed.

Aleppo

Hama

SYRIA

Homs

100 km

Damascus

Red building

White building

Execution room

(in the basement)

50 m

Sednaya prison

Military

zones

Tishreen

military

hospital

LEBANON

Damascus

Najha

(several

grave sites)

Qatana

(graves

in military

zone)

10 km

Source: Amnesty international, OSM and GoogleMaps.

RODRIGO SILVA - NACHO CATALÁN / EL PAÍS

In one of the kitchens, there are files on the prisoners scattered next to a kind of oven. Relatives are looking for the names of their loved ones. The impression is that the soldiers stationed in the prison fled in haste from the lightning advance of the rebels (which unexpectedly overthrew the regime in just a week and a half), and they did not waste time in burning them all. There were many, because a lot of people have passed through here: the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights says that 30,000 died from torture, mistreatment, and executions in the first decade of the war (2001-2011). Amnesty International estimated in 2017 that between 5,000 and 13,000 prisoners were extrajudicially executed in the first four years.

The cells are small and unsanitary. In some of them, dried marks of feces can be seen on the floor, and on the wall are the famous lines used to mark the time spent in prison. Prisoners have left engraved phrases such as “Punishment, 60 days,” “There is never mercy for our situation,” “Nice despite the sadness,” or, simply, “Goodbye.” It is daylight and already very cold. In a notebook bearing the name of a prisoner, only blank pages remain. The rest have been torn out.

The noise of families looking for their loved ones mixes with the sound of blows as men break the ground or dig in search of a supposed secret entrance, whose existence may be a myth, and to which many still cling so as not to give up their loved ones for dead or missing.

“Fear, fear, fear... that was the regime”

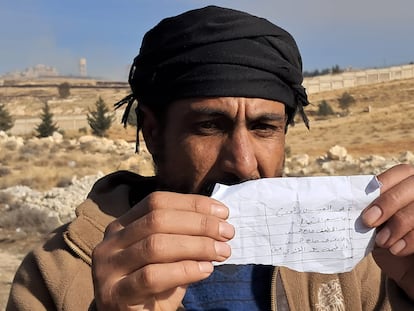

Suleiman Hayari has, he says, “first-hand information” that three of his nephews — Firas, Alaa and Rafaat — were held in the prison. “We don’t know anything, not even if they are alive. We were told they would be underground, but we haven’t found them. We are here for hope, for hope,” he repeats. His account is similar to others: an arrest at “a military checkpoint of Bashar al-Assad’s army,” he says, scornfully emphasizing the name of the recently deposed leader. What was the reason for the arrest? “They said he had weapons in his car, but it wasn’t true. They arrested people for nothing. For not being with him [Assad]. Fear, fear, fear… that was the regime, that’s what we had.”

Mariam Al Awiya prays that her brother Ahmed, who has been in prison for nine years, is in the notorious underground cells. “They have to bring the owner [the missing prison warden] who knows the codes [for supposed access to underground cells]. Maybe he is dying without food,” she says, before adding: “The same people who put him here called him a terrorist. Can you believe it?”

The underground cells have become a kind of Atlantis whose existence everyone wishes for, but no one confirms. Some speak of three floors underground; others of up to 10, to which access is urgently required because — without food (you can see it, rotten, in the kitchen) or water — every hour of delay can mean the difference between life and death. On Sunday, a rumor began to circulate that there were thousands of prisoners underground, controlled by an internal circuit, but that the lack of electricity has made it inoperable and only the guards (who have fled) know the access codes.

Crowds gather at any opening that leads below ground. Returning people warn those arriving that they won’t find anything, but they keep going down anyway: they need to see it with their own eyes. In the hurried conversations between the two columns, two phrases are often heard: “Is there anything?” and “Have you found them?”

Aman Al Usbuh cries inconsolably: “There are no cameras! They don’t exist!” He says that one of his brothers was arrested at a military roadblock in 2011, the year the revolt began, which was harshly repressed by Assad and degenerated into a civil war, and that he learned about it from an ex-convict in Sednaya, who was with him until 2018. He knows nothing about what happened to his brother between that year and this Monday (another day he went to the prison in the hope of finding him). “Where were the international organizations when all this was happening? Why do we have to be digging now to find my brother? We can only have faith in God until the last moment, because we believe in Him and everything is in His hands.”

In one of the cells, a middle-aged man, Waled Khalid Al Shamali, is tearfully showing a video of the rebels freeing the prisoners. The men can be seen looking skeletal or staring into space amid the shouts of joy from the fighters. Waled stops the video and says: “Look, this is my brother!”

— So he is alive and free…

— But we don’t know where. He’s disappeared. We’ve been coming here since Sunday to see if we can find him. Can you help us? Write down his name, please.

Today, here, the press badge — which normally arouses suspicion — attracts those who seek answers, beg the world for help, or simply need to vent their frustration. They stop the journalist on the road in the hope that he will provide them with the information they crave. “I’m looking for my brother, this is him. Do you know if he’s there?” says one, showing a name on a piece of paper. “Is it true what they say about the cell cameras?” asks another as his wife breaks down in tears.

With the rage of someone who feels abandoned by the world for too long, Hayari begs for a message to be passed on “to the United Nations and to the Arab countries” to “intervene as quickly as possible” to search for the prisoners in the basement. “It cannot wait,” he says, pointing up at the prison, surrounded by smoke from several fires in the surrounding area.

The situation is so chaotic and the place is so crowded that the armed rebels, exercising sole authority to keep things in order – both in the impossible traffic on the road from Damascus and at the entrances to the prison – decide to prevent further entry and evacuate the yard to avoid a stampede. The suddenly arriving police end up firing their rifles in the air to force people to obey the order. “There is my son, in a basement,” shouts an old man to a fighter, struggling to get in. “Let me through, I beg you!”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.