The Syrian regime was a paper tiger: Victorious on the outside; weak on the inside

The lightning offensive succeeded at a moment when Assad was widely regarded as the virtual victor of the war, had been reinstated in the Arab League, and Italy was actively exploring plans to facilitate the return of refugees to Syria

In the past decade, a former Lebanese Shiite fighter joined Hezbollah’s incursion into Syria, driven more by curiosity and solidarity with the militia than by any desire to support Bashar al-Assad’s army in combat. His account sheds light on the present situation, where the regime’s forces have lost key cities — secured over years of grueling warfare — in a mere 11 days. These losses occurred despite the long-standing support of allies such as Hezbollah, Iran, and, most critically, Russia, who no one expects today will intervene.

The former fighter recalls encountering an underprepared Syrian army, lacking both resources and morale. Hezbollah fighters, wary of friendly fire or potential acts of spite, took positions behind the Syrian soldiers. Many of these same soldiers have recently surrendered, defected, fled to Iraq, or retreated in the face of a swift rebel offensive. This offensive culminated in the early hours of Sunday with the capture of Damascus, the regime’s formal collapse, and Bashar al-Assad fleeing by plane.

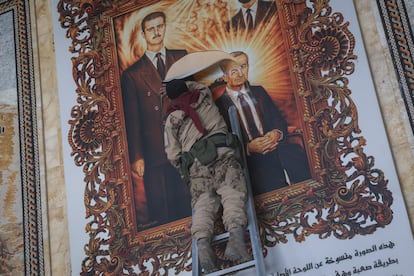

The 11-day blitz has revealed a stark truth: while “al-Assad” means “the lion” in Arabic, his regime was more of a paper tiger — fearsome on the surface but inherently fragile. His fall comes ironically at a time when he was being hailed as the de facto victor of a war that began in 2011. Arab leaders who once sought his ouster had recently reinstated him in the Arab League with warm gestures, and even European nations seemed more preoccupied with returning Syrian refugees than addressing his regime’s egregious human rights violations.

The Assad regime faced existential threats in the early years of the conflict until Moscow intervened in 2015, dramatically altering the balance of power. Gradually, the regime clawed back territory, securing 70% of the country, including major cities and the entire coastline. However, in 2019, a large-scale assault on Idlib — featuring heavy air and ground attacks by the regime’s elite forces — ended in failure. Despite killing hundreds of civilians and displacing 300,000 people, the military operation only captured 1% of the territory.

A year later, Turkey and Russia — the two most powerful backers of opposing sides in the conflict — brokered a ceasefire, ushering in a period of frozen conflict. Fighting continued, but the front lines remained largely static. A growing sense emerged that the only unresolved matters were for Damascus and Ankara to sort out control of the north — where Turkey had steadily claimed slivers of territory since 2016 — and to determine the fate of the Kurds. Idlib, the final rebel stronghold sheltering three million people (nearly two million of them displaced), no longer appeared to pose an existential threat to Assad’s regime.

At the time, Ankara was in negotiations with Damascus, and the potential return of refugees to Syria was a hot topic not only in Turkey and Lebanon — where anti-Syrian xenophobia had become commonplace — but also across the European Union. Several EU nations, spearheaded by Italy, were exploring the creation of “safe zones” within regime-controlled areas to facilitate refugee returns. Italy went so far as to reopen its embassy in Damascus this past summer, becoming the most significant EU country to do so 12 years after closing it.

However, these plans have been shattered in just 11 days. Like a trompe l’oeil painting on a crumbling façade, the regime’s apparent stability during the last five years of conflict was an illusion. Beneath the surface, Syria had been devolving into a narco-state, with its economy increasingly dependent on revenue from Captagon, a synthetic drug that is cheap to produce and widely trafficked. Jordan, for instance, reported Captagon shipments smuggled via drones en route to the lucrative Gulf markets. The trade enriched a select few, and — combined with the non-payment of debts to creditors — it prevented the complete collapse of an economy already suffocated by years of Western sanctions, a plummeting currency, and the banking crisis in neighboring Lebanon, where Syrian businessmen had traditionally safeguarded their assets.

During the four years of ceasefire, Syria’s humanitarian crisis worsened, with 90% of the population now living in poverty, according to the U.N. The government cut food and fuel subsidies. Meanwhile, two developments unfolded simultaneously.

In Idlib, while global attention shifted to other crises, the fundamentalist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) expanded its influence, blending governance functions with military preparation. The group established a military academy focused on rapid deployment units, drone production, and night vision training. Its leader, Abu Mohamed al-Julani, declared in May 2023 — five months before the Hamas attack on Israel that destabilized the region — that “military preparation had reached its zenith.” Addressing supporters, he added: “We are very close to reaching Aleppo. I see you sitting there, as I see you here today.”

At the same time, Assad’s three key allies — Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah — were forced to redirect their focus. Russia was mired in its war in Ukraine, Hezbollah was embroiled in conflict with Israel, and Iran faced its own strategic and economic challenges. These distractions weakened the coalition propping up Assad’s regime. The Syrian rebels had been preparing their surprise offensive for months but chose to strike when Hezbollah, significantly weakened and leaderless, was compelled to accept a ceasefire with Israel after nearly three months of bombings in Lebanon.

In just 48 hours, the rebels — primarily HTS and the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army — captured Aleppo, Syria’s second-largest city. This swift victory came despite Russian airstrikes attempting to halt their advance. On social media, a grim joke circulated: it was not Kyiv, as speculated early in the Ukraine invasion, but Aleppo that fell in three days — to the opposition.

By Thursday, Hama — Syria’s fourth-largest city and a historic symbol of rebellion — fell. Hama holds deep significance, as it was where Hafez al-Assad, Bashar’s father, brutally crushed a Sunni uprising led by the Muslim Brotherhood in 1982. Two days later, the rebels seized Homs, effectively severing communication between Damascus and the Alawite-dominated coastal regions — the Assad family’s heartland and the site of Russia’s naval and air base. By Sunday, the capital, Damascus, had fallen. The General Staff announced the regime’s collapse, and Bashar al-Assad fled by plane to an undisclosed location.

The swift rebel advance occurred without significant fighting, underscoring what Swiss-Syrian analyst Joseph Daher described as “the weakness of a regime” that relied heavily on its allies. “The majority of soldiers were not fighting to defend it,” said Daher, a professor at the European University Institute in Florence and author of Syria After the Uprisings: The Political Economy of State Resilience. “They did not want to lose their lives for a regime that treated them badly, paid them meager salaries, and commanded no loyalty. Most had been forcibly conscripted.”

Indeed, many adult Syrian men in Lebanon and Jordan — where they faced growing hostility — voiced their reluctance to return home, even after the fighting eased. When asked, they often replied: “I don’t want to be drafted for 10 years as soon as I cross the border.”

Military salaries

Syria’s armed forces are demoralized and exhausted after 13 years of civil war, burdened with meager salaries that barely sustain them. For years, it has been an open secret that soldiers, struggling to feed their families, participated in a black market, selling weapons and ammunition to members of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). Last Wednesday, as the regime’s collapse loomed, Bashar al-Assad announced a 50% salary increase for career soldiers. It was too little, too late.

Two recent images, intended to reassure regime supporters, instead highlighted the military’s dire condition. One was a video of regime troops moving to reinforce Hama’s defenses, in which many were seen walking, instead of traveling in military vehicles. The second was Syrian Defense Minister Ali Mahmoud Abbas’ appearance on state television Thursday evening. Not only because he was mechanically reading a speech that would become absurd by Sunday — claiming the military was “in a good position on the ground” and that retreats were tactical — but because the backdrop featured outdated decor and four antiquated landline telephones.

Syria is now, as rebels declared upon taking Damascus, “free of Assad.” The allies who rescued his regime from collapse after 2012 were either unwilling or unable to do so this time.

In October, Hezbollah withdrew its forces from Syria (including senior commanders tasked with defending Aleppo, according to Reuters) to focus on the Israeli invasion of southern Lebanon. Following Israel’s assassination of Hezbollah’s leader Hassan Nasrallah in September, his successor, Naim Qasem, delivered a speech on Thursday affirming support for Syria: “We will stand by Syria to frustrate the objectives of the aggression,” he said, though with a notable lack of detail, adding only, “as much as we can.” This was a far cry from the thousands of fighters Hezbollah had once deployed to defend Assad’s regime. Two days later, its elite forces withdrew from Homs.

Iran had already scaled back its military presence in Syria, and Russia was evacuating its naval base rather than reinforcing it — clear signs that Moscow deemed the battle unwinnable. Halting the rebels’ advance would have required a significant foreign troop deployment, but instead, foreign forces were leaving the country, not entering it.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.