Fame, money and ties to the Jalisco New Generation Cartel: The clues behind the murder of Jesús Pérez Alvear

The music promoter, linked to artists such as Gerardo Ortiz and Julión Álvarez, was gunned down in one of the most luxurious areas of Mexico City. The US had pursued him for years for alleged links to drug trafficking

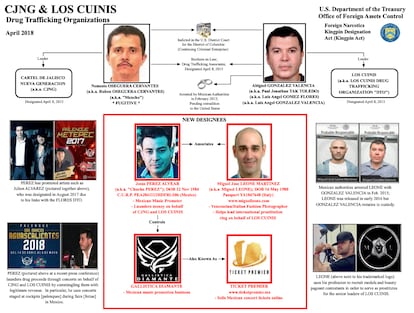

The execution lasted less than a minute. The gunmen opened fire in a restaurant in Plaza Miyana in Polanco, one of the most luxurious neighborhoods of Mexico City, and by the time emergency services arrived it was too late. The attack shook the capital, which has repeatedly taken refuge under the illusion that drug violence is a phenomenon that affects only the states in the interior of the country. But when the authorities confirmed the identity of the victim on Thursday, the case took on another dimension. It concerns 40-year-old music promoter Jesús Pérez Alvear, “Chucho,” known for representing and dealing with superstars of the Mexican regional genre such as Julión Álvarez and Gerardo Ortiz, although also for having been in the sights of the U.S. authorities for years. Washington had accused him of laundering money for the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), including him on the so-called “black list” of the Treasury Department and issuing an arrest warrant to bring him to trial two years ago. On December 4, he was shot dead at point-blank range while he was eating with two men and a woman.

Drug trafficking and fair tickets

The story began in April 2018, when Pérez Alvear was identified by U.S. authorities as one of the financial operators of the CJNG, one of the most feared and powerful criminal organizations in the world, as well as Los Cuinis, the cartel’s armed wing. The White House said that Chucho used Gallística Diamante, an events management company founded in the state of Aguascalientes, to launder money from both criminal groups and help them finance the “opulent lifestyle” of their leaders. “Chucho Pérez has close ties to the family of González Valencia, and focuses primarily on promoting concerts staged during large Mexican fairs, such as those held in Aguascalientes and Metepec,” the statement read.

The victim had a romantic relationship with one of the sisters-in-law of Nemesio “El Mencho” Oseguera Cervantes, the founder and top boss of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, according to Mexican media. That link allowed him to establish financial ties with the CJNG and Los Cuinis, commanded by the Mencho political family. Washington claimed that Gallística Diamante, which used the commercial name Ticket Premier, was a key piece in the modus operandi to launder money.

Chucho perfected a method to combine illegal profits from the CJNG with legitimate income obtained by his company, such as ticket sales, food concessions, and parking fees. The head of the company operated in a gray area: he had a legal business, but he incorporated drug trafficking techniques in order to grow. “Chucho Pérez uses violence to obtain concessions to operate these concerts under the name of his music promotion business,” the Treasury said.

Aside from the crimes he was accused of, the United States was also concerned by the theme of the events. “Chucho Pérez often promotes musical acts known for singing narcocorridos, or ballads that glorify drug traffickers and their illicit activities,” the statement stressed. Only one artist was mentioned in the bulletin announcing the sanctions, which froze his assets and closed the doors to the international banking system: Julión Álvarez. The singer had been sanctioned in August 2017 on the same grounds: laundering drug money.

That round of sanctions was not without controversy, because the so-called “blacklist” also included soccer star Rafa Márquez, one of the best Mexican players of his generation. After a long battle to clear his name, Márquez was removed from the list in 2021. Álvarez has for years also denied alleged links to drug trafficking. The controversy surrounding Chucho, however, came from another idol of the masses: Gerardo Ortiz.

The concert scandal

Chucho’s appointment as CJNG operator got in the way of his business. Plans were already underway for an Ortiz concert at the San Marcos Fair in Aguascalientes, scheduled for April 27, 2018, three weeks after the sanctions were announced. Pérez Alvear served as the Mexican manager for the singer and other artists from the Del Entertainment label. At first, confusion reigned, and executives were almost convinced that the best thing to do was to cancel the event. Employees at the label had drafted a statement saying that Ortiz “had no choice but to abide by U.S. laws” and not schedule any shows organized by individuals sanctioned by the State Department. But the statement was never published.

Nine days before the concert, two FBI agents intercepted Ortiz at the Phoenix International Airport in Arizona to inform him that, as an American citizen, he was prohibited by law from any dealings with Chucho. That same afternoon, the record label executives exchanged text and voice messages to try to turn things around. They talked about hiding the links with Pérez Alvear and his company, but at the same time being able to collect part of the money that the promoter owed them while creating “a paper trail” that would hide the participation of the promoter and Gallística Diamante in the organization. “He is under surveillance,” they warned. In the days before the show, the company decided to go ahead with the event, despite the warnings from the authorities.

According to the U.S. authorities, Chucho bought a disposable cell phone to negotiate with one of the record company’s top executives on how to get around the sanctions. They discussed, for example, the possibility that the Aguascalientes authorities would write a letter to show that Ortiz was going to appear at their request and not at Pérez Alvear’s, who was really the beneficiary of the concert taking place. They also talked about paying in advance for the rental of a private jet so that the artist could sing on the agreed date and the show would not be cancelled. The executives paid two million pesos (about $100,000) and, despite some setbacks, the singer performed in front of his audience.

From that moment on, the executives stopped mentioning Chucho and referred to him instead as Pedro so that there would be no trace of the transactions. And the concerts continued with Gerardo Ortiz and other artists represented by Del Entertainment, also organized by Pérez Alvear but paid for by front men or through financial triangulations to try to deceive the authorities. The money machine did not stop running. The promoter organized Ortiz shows with dates in Querétaro, Guanajuato, Nuevo León, Sonora, Campeche, Baja California, Hidalgo, Tlaxcala, Sinaloa, the State of Mexico, and Michoacán. All of them were held in 2018, despite the sanctions. There were at least four other performances in early 2019. During that period of time there were payments to the record label through Pérez Alvear’s front men for about three and a half million pesos.

Everything appeared to be proceeding as planned, but in reality the U.S. authorities were aware of every move. They discreetly tapped Chucho’s phones, accessed his financial statements in collaboration with their Mexican counterparts, and eventually obtained search warrants to seize all the evidence. In 2020, when there was no longer a working relationship between Del Entertainment and Gerardo Ortiz, the authorities raided the offices of the record label. “[The FBI] took several materials that we understand are related to their investigation into our former artist,” the company said. Ortiz later sued his former label for breach of contract and fraud that caused him to lose “tens of millions of dollars.”

It was not until June 2022 that the arrest in California of Jorge del Villar and Luca Scalisi, the director and financial head of the record label, respectively, was announced for the crime of conspiracy to make transactions with an individual sanctioned by the authorities as a criminal kingpin. In addition to Del Entertainment, the third defendant was Pérez Alvear. “He is believed to be in Mexico,” the statement said. Scalisi and Del Villar faced 14 charges for alleged financial crimes and, if found guilty, could be sentenced to up to 30 years in prison. The detainees paid bail of hundreds of thousands of dollars and have faced the judicial process in freedom. Ortiz was not charged by the authorities. Nor has he spoken out after the murder of his former manager.

The attack

In May 2023, Chucho reached an agreement with the United States authorities and pleaded guilty. Pérez Alvear confessed that he participated in the conspiracy in exchange for a maximum sentence of 10 years in prison and the payment of a fine of $250,000 or double the profits he obtained from the irregular transactions. In the court file, to which this newspaper has had access, there is no indication that the promoter has been sentenced. Scalisi and Del Villar maintain their innocence and the case is still ongoing in a California court.

Mexico City police revealed that Chucho arrived at the restaurant two hours before his murder, a direct attack, according to the main line of investigation. Two men carried out the attack. Omar García Harfuch’s Security Secretariat confirmed the identity of the victim. After the murder, Pérez Alvear has also been linked to the CJNG attack against Harfuch, then head of the Mexico City Police, in 2020. One of the versions of events is that, for that reason, he remained a target of the Mexican authorities despite his agreement with the U.S. justice system.

After news of the attack was leaked, the way the hitmen escaped was also revealed. They left the shopping mall and fled on a motorcycle. The victim’s companions collected their belongings and also left the place immediately. “This incident, like others, will not go unpunished,” said the authorities.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.