The 11 days that dealt Hezbollah its most crushing defeat in history

The detonation of thousands of pagers and walkie-talkies and the killing of the Lebanese militia’s leaders clearly demonstrates Israel’s ability to turn the tables, thanks to its military and technological superiority, and undisputed support of the United States

In 2006, after 34 days of war with Israel, Hassan Nasrallah — the leader of Hezbollah who was found dead on Sunday — admitted in an interview that, if he could go back in time, he would not have ordered the surprise attack on a military patrol that sparked the conflict. “We did not think, even 1%, that the capture would lead to a war at this time and of this magnitude. You ask me, if I had known [...] that the operation would lead to such a war, would I do it? I say no, absolutely not.”

If this is what he thought after a conflict that ended in a moral victory and a surge in popularity for Hezbollah, who were celebrated for facing such a superior enemy, it is hard to imagine what Nasrallah, if he were alive, would think after the 11 days in which Israel has dealt the group its most crushing defeat. A blow that is a reminder of a reality that is often clouded amid fear and rhetoric: Israel’s military and technological superiority is indisputable. As is the support of the United States

The Lebanese militia was also unknowingly infiltrated to its very core. Meanwhile, its main supporter, Iran, watched from a distance as the conflict descended into an open war against Israel (and perhaps Washington, which mobilized aircraft carriers) that it neither wants nor can win.

The result has placed in Israel in what may be its best strategic position in almost a year. Just two weeks ago, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu appeared to have run aground in Gaza, with no direction other than preserving his power, the ongoing devastation and the search for Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar. Today, he once against appears all-powerful. And unpunished: his army has killed almost twice as many Lebanese people (more than 1,000) in 11 days as in the previous 11 months, and a higher proportion of civilians. He has also forced the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people, who are now sleeping in schools, apartments and even streets and parks in Beirut.

Hezbollah, just as in 2006, did not expect the conflict to go so far. The attack on October 7, 2023, caught it as much by surprise as it did the Hamas political leadership in exile. But when the Israeli army began to bomb Gaza in retaliation, it felt obliged to open a new front, in defense of its ally and Iran’s strategy. On October 8, it fired rockets at the Shebaa Farms — since 2006, the United Nations has been calling for negotiations to resolve the dispute over this territory, which Hezbollah claims — and began an exchange of cross-border fire. In his addresses, Nasrallah described the actions as a triumph for Hezbollah, because they forced Israel to divert military resources from the Gaza Strip and evacuate 67,000 civilians.

As Israel continued to bomb Gaza, so did Hezbollah. In waves that intensified, and targeted areas that were increasingly further away from the border. The fighting only stopped during the week-long ceasefire in the Gaza Strip, in November 2023. Both sides crossed red lines, but continued to adhere to unwritten rules: Israel — responsible for 80% of the shelling — killed militants with fairly precise strikes and Hezbollah only targeted military targets. Only when a bomb (apparently by mistake) killed 12 minors in the Golan Heights (Syrian territory occupied by Israel) did Netanyahu go after Hezbollah’s number two, Fuad Shukr.

Unsustainable situation

The situation proved unsustainable. In Israel, displaced people were increasingly demanding that Hezbollah be crushed so they could return home. In its measured and belated response to Shukr’s killing, Hezbollah made all too clear its fear of open war, either out of strategy, weakness or a mixture of both. Its missiles and drones did not stop Israel’s deadly attacks in Gaza, and its fear of all-out war became “a sign of weakness,” in the words of analyst Joseph Daher, a professor at the European University Institute in Florence and author of the book Hezbollah: The Political Economy of Lebanon’s Party of God.

Israel smelled blood. Months earlier, it had introduced explosives into the thousands of pagers and walkie-talkies ordered by the party-militia and decided that now was the time to strike: Gaza was no longer in the spotlight, the U.S. was focused on the elections, and the new president of Iran, Masoud Pezeshkian, looking to the West to renegotiate the sanctions and the nuclear dossier. The Mossad detonated the devices remotely — over two days, to increase the impact and confusion. Hezbollah lost hundreds of men, lines of communication and confidence.

Since then, Hezbollah’s top leaders have been killed one after the other. The most recent victim was Nasrallah, who had survived previous assassination attempts, was not using electronic devices and had barely seen people in the last two decades. The moral blow to his followers is so great that on Sunday, some were claiming that he was still alive and that Hezbollah was planning a dramatic strike.

Israel’s 11-day Israeli lightning offensive has left Hezbollah facing “its most difficult moment” in four decades of history, Daher says by telephone. Israeli warplanes have gone from causing sonic booms over Dahieh — the Hezbollah stronghold on the outskirts of Beirut where Nasrallah was killed — to scare the population, to bombing it every few hours. Israeli warplanes are also flying over the main entry points, such as Beirut’s civilian airport, ports and the border with Syria. Even in the Christian district of Achrafieh, the constant buzz of Israeli drones could be heard on Sunday. Just like in Gaza.

Hezbollah has survived other assassinations. Like the killing of Abbas al-Musawi, Nasrallah’s predecessor, in 1992. Or the assassination of Imad Mughniyeh, who was killed in a car bomb in Damascus in 2008. “But it has never suffered such a serial decapitation of military and political leaders,” says Daher. “Does this mean that this is the end of Hezbollah? No […] It can continue to act politically and militarily.”

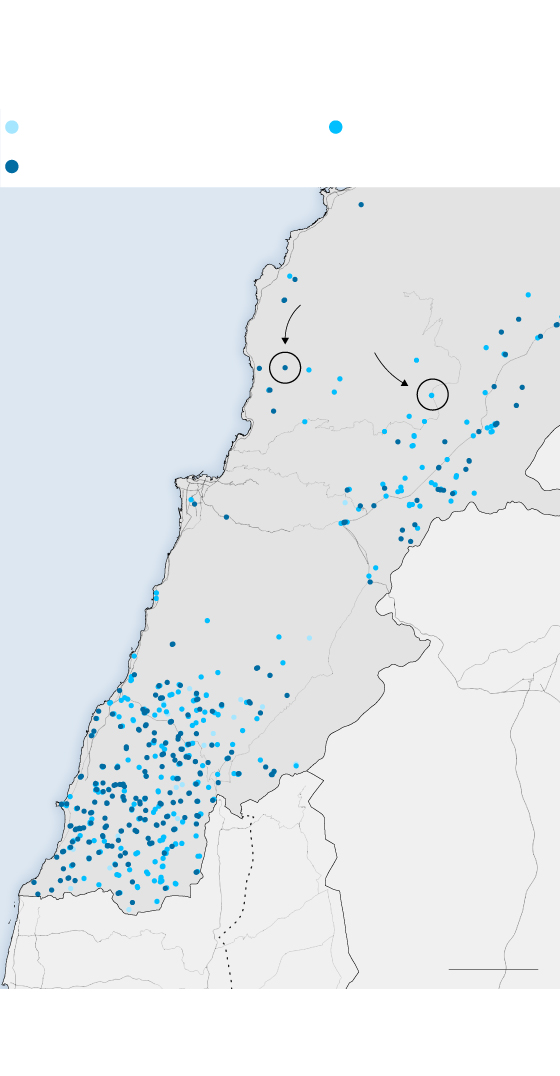

Israel bombardea Líbano

durante una semana

21 y 23 de septiembre

23 y 24 de sep.

25, 26 y 27 de sep.

LÍBANO

Mar

Mediterráneo

Bombardeos

de Israel

Beirut

Sidón

Tiro

SIRIA

Altos del

Golán

ISRAEL

20 km

Fuente: ISW.

LUIS SEVILLano / EL PAÍS

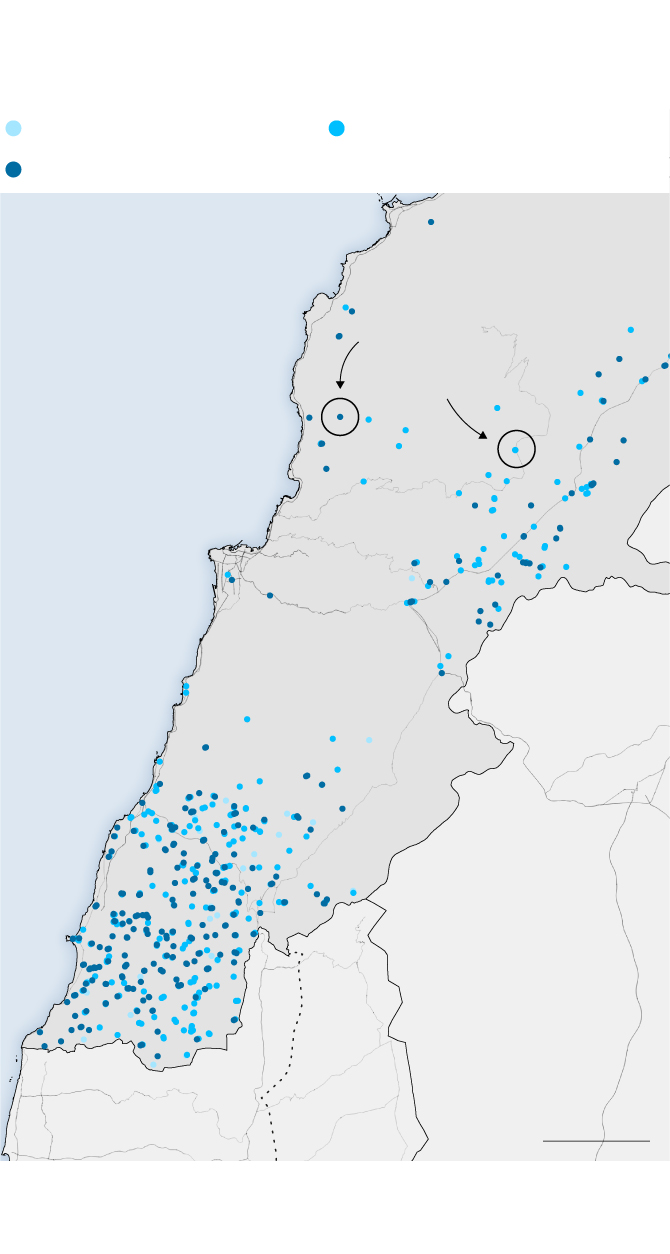

Israel bombardea Líbano

durante una semana

21 y 23 de septiembre

23 y 24 de sep.

25, 26 y 27 de sep.

LÍBANO

Mar

Mediterráneo

Bombardeos

de Israel

Beirut

Sidón

Damasco

SIRIA

Tiro

Altos del

Golán

ISRAEL

20 km

Fuente: ISW.

LUIS SEVILLano / EL PAÍS

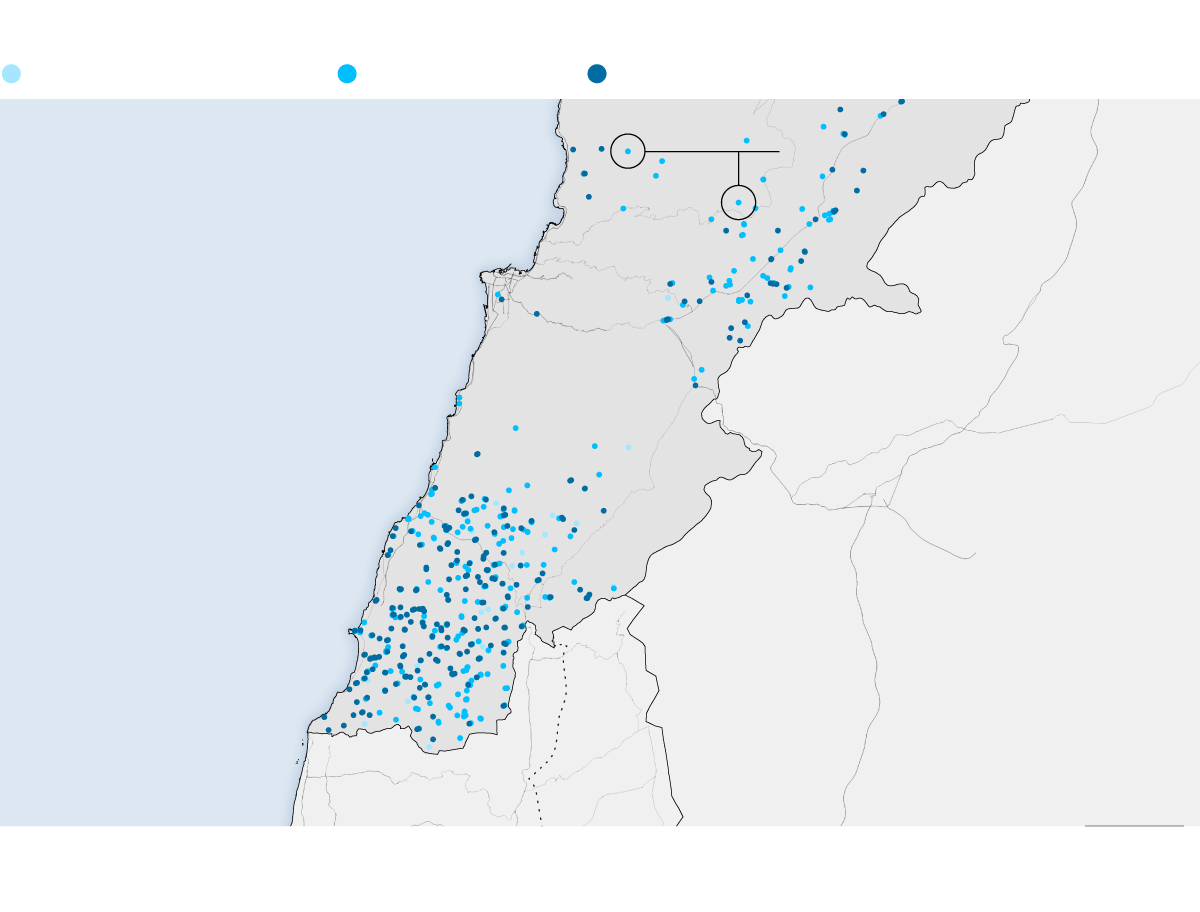

Israel bombardea Líbano durante una semana

21 y 23 de septiembre

23 y 24 de sep.

25, 26 y 27 de sep.

Bombardeos

de Israel

Beirut

Mar Mediterráneo

LÍBANO

Sidón

Damasco

SIRIA

Tiro

Altos del

Golán

ISRAEL

20 km

Fuente: ISW.

LUIS SEVILLano / EL PAÍS

Abed Kaananeh, an expert at Tel Aviv University’s Middle East Department and author of an essay on Hezbollah, elaborates: “It was a big blow. Not just for those who support him. He was much more than just the secretary general of Hezbollah. For many people in the Arab world, he represented the resistance to Israel. But it does not mean the end of Hezbollah or the war in the north.”

In Israel, where journalists celebrated Nasrallah’s assassination live on television, Kaananeh calls for caution. It is “too early” to gauge the group’s ability to plan retaliation. “It needs a few days to understand how to react. And, above all, how the Israelis were able to infiltrate so deeply. They need it to be able to protect the next leader,” he says.

Daher recalls that Hezbollah — considered a terrorist group by the U.S. and the EU, which combines pragmatism with an Islamist concept of resistance that leaves no room for surrender — preserves a good part of its arsenal, including guided missiles.

The shockwaves of these 11 days will be felt throughout the Middle East, especially in Iran. For 11 months, it kept its pieces in motion (some more unruly, others less so) on the geopolitical chessboard. The attacks against Israel from different points helped Tehran achieve its main objective: “Improving its strategic position in terms of negotiations with the West,” says the expert.

Without aspiring to have the same power as the alliance between Israel, the United States and much of Europe, it was the ace that Iran had up its sleeve, o hide or pull out at will: a combination of militias in Iraq and Syria, the Houthis in Yemen, Islamic Jihad in the West Bank, and, of course, the “jewel in the crown”: Hezbollah. Iran needs to carefully calculate when to use this card, because the threat of doing so is part of its deterrent power.

Today, Hezbollah’s powder has been severely damaged, which leaves Tehran in a delicate spot. Daher explains: “Hezbollah is not just a puppet of Iran. It has its own autonomous interests, too. But if one loses, the other loses too. The fact that Hezbollah has been weakened also leaves Iran weakened.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.