Uruguayan children connect through handwritten letters in a digital age

The project aims to join students from diverse backgrounds, while stimulating their imaginations, motor skills and concentration

Last October, Aaron Álvarez went for a walk in a Montevideo park and saw a giant castle. The nine-year-old boy then wrote a letter about the castle that belongs to the president of Uruguay. “I don’t know why the president has a castle called the Suárez residence,” he said in a handwritten letter that made its way to Guadalupe Vélez, a 12-year-old student at a rural school in Maldonado (eastern Uruguay). “A castle!” Guadalupe read incredulously. “A castle?” her companions asked. All eyes turned to the teacher, who told them about the century-old mansion situated on Suárez Street in the Uruguayan capital, which has been the presidential residence since 1947. The president’s castle, according to Aaron.

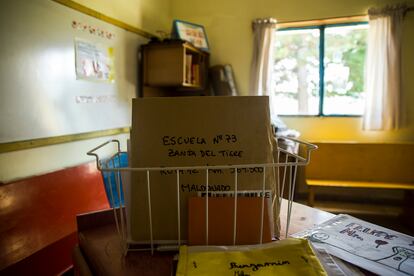

Since mid-2023, Guadalupe has been corresponding with Aaron and Isabella Otero, who are both nine years old and third-grade students at a school in Melilla, a suburb of Montevideo. “It was the first letter I ever wrote,” said Guadalupe. The seven boys and girls in her class also participated in the letter-writing adventure. “I wrote about how my dad gets honey straight from the hive,” said Florencia Dayuto. “I wrote about how olive oil is made,” said Sergio Rodríguez. “And I wrote about branding cattle,” said Evaristo Moreira. In their letters, they described the mountains encircling the school, the spacious playground, how they identify birds by their songs, and the near-constant breeze.

“We tell them to write whatever they want – to express themselves freely,” said Mónica Sosa, a teacher at the Maldonado school. The letters are sent by mail to Montevideo and replies arrive soon after from their pen pals in the capital. It’s all part of the De puño y letra project, which means “Handwritten” in English. One aim of the project is to connect students from rural and urban schools throughout Uruguay. “I don’t really intervene, I just kind of guide them,” said Sosa. In this initiative, curiosity reigns, allowing for unhurried writing. Patience is nurtured, a valuable quality in an era of instant messages, keyboards and auto-corrections.

The project began in Salto (northwestern Uruguay) to foster connections between rural and urban children, says project coordinator and teacher, Inés de Lisa. In May 2023, her 21 students from the Laureles school wrote letters to children in El Pinar, in southern Uruguay. “The kids were super excited! It was totally new for them to write a letter by hand, you know, just casually.” By the end of the year, nearly 800 children in 43 schools all over the country were participating in the project.

“The key benefit of this project is that it fosters empathy, trust and an understanding of diversity,” said Carlos Guinovart, an agricultural engineer and artist. Guinovart helps manage the project with De Lisa and Gabriela Zabaleta, who works as a cultural promoter in El Pinar. “This sentiment is shared not only by the children and teachers, but by everyone familiar with the project. Whenever we needed help, it was promptly provided,” he said. Uruguay’s national postal service helped by collecting and delivering letters for free. “It’s like a very long chain of favors.”

The children at the Maldonado school were surprised when they received letters from their peers in the city describing all the things city kids get into. “They have different classrooms, workshops and complicated schedules,” said Evaristo. Seated next to him are Indiana García (12), Tiziano de los Santos (8) and Renato García (7). Tiziano and Renato are the youngest of the Maldonado group and the biggest video game fans. Nevertheless, they pitched in with their own drawings and letters. Anthony Casañas (12) confessed, “I’m more of a talker.” But when his turn came, Anthony focused on the task, crafting his stories and mastering the art of punctuation. His sentences were famously long, leaving readers breathless and often chuckling.

“Handwriting is part of your identity – no two people have the same handwriting,” said De Lisa. She also noted other important benefits for childhood development, such as imagination, motor skills and concentration. Writing with pencil and paper helps develop motor skills that are crucial in various parts of life. And cursive writing stimulates specific brain functions that are not engaged when writing in block letters or when typing. “That’s why handwritten letters are a challenge, an adventure,” she says.

Gabriela Zabaleta also mentions another impact of the project on her students at El Pinar: they started to appreciate the value of taking their time and enjoying the moment. “It’s the kind of time that allows for slow writing, grabs your attention, and makes it worth the wait for a response.” She says it’s a novel experience for children who have grown up with electronic devices. Aaron, the boy who visited the “president’s castle,” summed up his experience: “At first, I thought it was kind of boring, but I actually started to really like it. Writing letters is the most fun thing in the whole world!”

Letter excerpts

- "Hey Fabrizio! Remember when I mentioned that after school we'd go bug hunting with the kids in the countryside? Well, the mules had babies and we couldn't catch them. But then my cousin actually got sprayed by a skunk and my aunt had to clean it off with tomatos." William Piriz (11).

- “Hello, Jazmín Britos, it was a pleasure to receive your letter. You mentioned being the best player on your team and you're a goalkeeper. I also enjoy playing in the goal, perhaps due to my quick reflexes. You also mentioned wanting to become an Arab dance teacher. I wish you success in achieving your goals." Evaristo Moreira (11).

- “I'm super indecisive. Like, when it comes to food, I can't pick a favorite because I like so many of them. I like every kind of animal and all birds. They're just so adorable and sweet. There's so much more I wanna tell you, but I ran out of paper here." Sergio Rodríguez (8)

- “Hello, new friend, I'm Faustina, I go to Rural School number 85 in Florida. I'm 7 years old and I'm in the second grade. I have 3 siblings, Olivia, Mía and Juan. I like horses. What animals do you like? How old are you? Do you know cursive? My dad he taught me to ride a horse. I'm sending you a feather as a gift. We found it on the way to school." Faustina (7).

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.