Chile’s 2023 constitutional referendum: Where the political parties stand

The South American country’s political actors have all staked their positions on the new constitutional text, causing some internal divisions within the parties

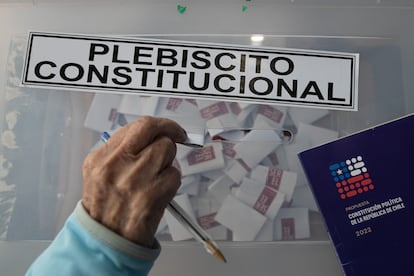

After more than a month of electoral campaigning, Chilean political parties are preparing to receive the results of the constitutional referendum. This Sunday, December 17, the parties for and against the project drafted by the Constitutional Council will find out the citizenry’s final decision on the text.

The constitutional proposal, which was drafted by a council dominated by the extreme right of the Republican Party and the traditional right of Chile Vamos (Let’s Go Chile), which holds 33 of the body’s 50 seats, received majority support from the political parties opposed to President Gabriel Boric’s left-wing government. The ruling party and the center-left, which did not play much of a role in shaping the constitutional initiative, staunchly oppose the project.

The president has decided to remain silent on the new constitution, although all the parties that support him are against the initiative.

The parties in favor of the project

Proponents of the proposed new constitution include the far-right Republican Party (PLR), as well as Chile’s traditional right-wing coalition Vamos, which is made up of Renovación Nacional (RN, National Renewal), Unión Demócrata Independiente (UDI, Independent Democratic Renewal) and Evolución Política (Evópoli, Political Evolution). They are joined by the centrist parties Amarillos por Chile (Yellows for Chile) and Demócratas (Democrats), founded by former members of the defunct center-left alliance Concertación [which means conciliation], which governed Chile between 1990 and 2010. Another movement that officially favors this option is the populist Partido de la Gente (PDG, People’s Party), led by former presidential candidate Franco Parisi.

The parties against the initiative

The bloc opposing the Constitutional Council’s project is primarily made up of progressive groups, including the center-left Democratic Socialism coalition (formed by the Socialist Party, the Party for Democracy, the Radical Party and the Liberal Party), the Broad Front (made up by Convergencia Social [Social Convergence], Revolución Democrática [Democratic Revolution] and Comunes [Commons]), the Communist Party, Acción Humanista [Humanist Action] and the Federación Regionalista Verde Social [Green Regionalist Social Federation]; all of these political forces form part of Boric’s government. Beyond the groups that comprise the executive branch, the Christian Democratic Party and smaller leftist parties like Patria Progresista (Progressive Party), Partido Popular (Popular Party), Partido Alianza Verde Popular (Popular Green Alliance Party), Partido Igualdad (Equality Party) and Partido Humanista (Humanist Party).

Internal divisions and opposition on the Right

The Chilean constituent process has caused divisions within some political parties, especially on the Right. In particular, internal disagreements affected the Republican Party, which led the drafting of the new constitution and had expressed its opposition to changing the current constitution during the first process. Several prominent conservatives questioned the Republicans’ about-face and maintained their firm position against changing the constitution.

Senators Rojo Edwards (who resigned from the Republican Party), Juan Castro and Alejandro Kusanovic (both independents with ties to the traditional Right) announced their position against the change, as did deputies Johannes Kaiser, Roberto Arroyo, Gloria Naveillán, Enrique Lee, Francisco Pulgar and Gonzalo de la Carrera. Centrist political parties, which largely support the change, also expressed their opposition to this project: Congressman Jorge Saffirio (of the Democrats) announced his stance against the project. In addition, the three PDG deputies confirmed their votes against it, despite the fact that their party has campaigned for it.

A party that supports both positions

The Partido Social Cristiano (PSC, Social Christian Party) broke the campaign schemes for the constitutional plebiscite. The right-wing party, formed by groups tied to evangelical churches, was divided with members taking both positions. For the electoral slot, the television space granted for broadcasting audiovisual electoral ads, the group appeared in the blocks allowed for both positions but expressed a common concept: whatever the result of the plebiscite, the constituent process must be terminated.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.