Cryptocurrencies, chemicals and drugs: the menu of international fentanyl trafficking

Mexican drug traffickers, suppliers in China and consumers in the US are the principal actors in the fentanyl supply chain. According to several studies, Bitcoin is the most common form of payment for illicit transactions, which have skyrocketed in recent years

The laboratories put the options on the table for the drug traffickers. It’s an à la carte menu, similar to that of classic restaurants, which leaves little to the imagination. Oftentimes, the product on offer is usually accompanied by a photograph, the chemical formula and the price. If the substance is banned or regulated, that’s not a problem. If the client wants to have a variety of options to make the payment, or needs the merchandise to be delivered immediately, there’s also not an issue.

“These are the typical lists that one would find on Amazon or on any digital commerce platform,” says Eric Jardine, chief investigator of the cybercrime unit at Chainanalysis – a security company specializing in cryptocurrencies. Several recent studies have exposed how criminal networks for the international trafficking of fentanyl and other synthetic drugs operate. This illicit supply chain spans the pharmaceutical industry in China and India, Mexican cartels and end users in the United States. It even reaches unsuspected terrain, such as North Africa, Eastern Europe, or Oceania. Everything is reachable with just a click.

Fentanyl is the latest protagonist in the war on drugs in the United States, where, each year, tens of thousands of people die from overdoses. And this time around, it’s not a battle like the previous ones. Fentanyl is more powerful, cheaper and easier to produce than traditional narcotics, which translates into higher profit margins, as well as an easier process of trafficking the drug in small doses. There are also many recipes that can be used to make it… and many of them start with substances that, for the most part, are legal and easy to obtain. These substances are known as “precursor chemicals.”

Raúl Martín del Campo – a planning director at Mexico’s National Institute of Psychiatry – points out that, 10 years ago, we only knew of four different types of fentanyl. Today, there are more than 50 variants on the illegal market that use different precursor chemicals. This has made the battle against drug-trafficking much more complex. It’s no longer just about intercepting phone calls, arresting drug lords and confiscating the merchandise. On top of all of this, it’s now necessary to negotiate with various countries regarding the regulation of commonly-used chemical compounds, while also monitoring how online sales take place before the goods reach the black market.

Sometimes, the methods to fly below the authorities’ radar are crude, but effective. Jardine’s team easily accessed sites on the so-called “deep web” – a part of the internet that offers greater anonymity to users and cannot be accessed via traditional means – where US traffickers offer fentanyl under the nickname “China White,” as the drug is commonly known on the streets. On one of the webpages, for example, a gram of “high quality” fentanyl is sold for $100 and can be delivered from the United States to anywhere in the world. If the client purchases 10 grams, there’s a 10% discount: he only has to pay $900.

Three grams of fentanyl can prove lethal. But the business model is solid. Calculations by US authorities indicate that producing a kilo of fentanyl costs the drug lords around $800… but on the streets, that same amount of drug earns them more than a million dollars.

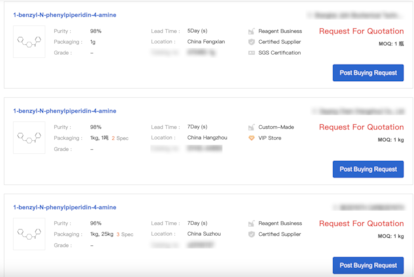

The products aren’t usually promoted with commonly-used names. Instead, vendors utilize scientific formulas and offer different suppliers, especially when it comes to precursor chemicals. The latest Chainalysis study includes a screenshot of a website, where three options are offered to the client, with different origins and degrees of purity, with amounts ranging from one gram to 25 kilos. Wait times are between five days and one week. Buyers – who can see reviews of the manufactures that have been posted by other customers – can engage in bids to snap up the items.

Jardine notes that there are all kinds of online stores that sell these products. Businesses resort to traditional marketing tactics – such as search engine optimization (known as SEO) or customer service – to clarify doubts. “In general – and from what we have observed – these services aren’t really trying to hide what they’re selling,” the specialist explains.

Elliptic – another company specializing in cybersecurity and cryptocurrencies – has identified more than 90 Chinese pharmaceutical companies that are willing to sell precursor chemicals, including substances that are restricted in other countries (but legal in China). Among them, 17 of these firms sell finished versions of fentanyl without restrictions. During their investigation, Elliptic’s employees posed as Mexican drug traffickers, so as to be able to deal directly with drug manufacturers. “Suppliers were not concerned about what the chemicals were going to be used for… some even explained that this or that precursor [chemical] was one of their best sellers and could be used to make fentanyl. Others openly said that they had already sold it to clients in Mexico,” read the latest report released by the firm.

Sometimes, transactions are agreed to over email, where details about the products and the cost of shipping are discussed. The possibility of the chemical products being delivered from door-to-door can also be put on the table. Last week, the US Treasury Department blacklisted 17 Chinese citizens and companies, on the grounds that they have provided drug cartels with key inputs, such as pill presses to make contraband pills.

In response to Washington’s insistence that the epicenter of the global fentanyl trade is in Asia, Beijing issued a stern statement, emphasizing that the allegations are typical of “a plot in the style of Hollywood movies.”

“A knife can be used to cut vegetables or to kill a person. If someone were to attack others with a knife, who is to be held accountable? The one who used the knife, or the one who made it? The answer is clear,” said Mao Ning, a spokeswoman for the Chinese Foreign Ministry. China insists that it has made progress in its regulation of the sale of chemicals, but insists that it will not assume responsibility for a problem “made in the USA,” to use Ning’s words.

The money trail

Specialized studies suggest that scenes out of Hollywood – in which briefcases full of money are delivered to close deals – are becoming less and less common. This is where cryptocurrencies come in. Criminal groups resort to them, because they allow payments to be instantaneous and wired to any part of the world, with no governmental supervision and with pseudonyms replacing real names. In 2022, cryptocurrency transactions associated with illegal and criminal activities exceeded $20 billion – up $2 billion from a year earlier – according to calculations by Chainalysis.

When DEA agents infiltrated the Sinaloa Cartel, they saw that the use of cryptocurrencies made it possible for the drug lords to move millions of dollars, without the money being detected by the financial system. All of these illicit funds could later be easily converted into traditional currencies. Nine out of 10 Chinese labs that sell fentanyl or precursor chemicals accept cryptocurrency payments, according to the Elliptic study. Despite the fact that the use of these platforms is restricted in China, pharmaceutical providers use open portfolios in other countries, or resort to intermediaries to facilitate operations. The company says that “Bitcoin is by far the most popular cryptocurrency” among the laboratories analyzed, followed by Tether, a cryptocurrency that has gained popularity because it has a fixed exchange rate equivalent to one US dollar.

Despite the veil of secrecy around cryptocurrencies, Jardine explains that transactions are traceable. “There’s a misconception that there’s an inherent privacy to cryptocurrencies, that nobody knows who’s behind these operations… but this isn’t the case,” he emphasizes. The specialist says that there’s a kind of ledger – a record of all transactions – in a chain of blocks. “The tricky thing is that the payment addresses we see are just a bunch of characters… [they’re not identifiable] in the real world. So, there’s a degree of anonymity to the whole process.”

What cybersecurity companies do is overlay known data from said addresses or digital wallets. This allows them to know more about who is behind the transactions and what the money is being used for. For instance, once the payment references are linked to a specific laboratory, specialized companies can track each of their operations and locate where the money is flowing from, allowing them to identify accounts with similar activity.

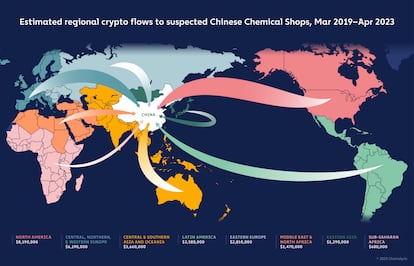

A handful of users associated with Chinese laboratories have had commercial income flows of more than $38 million over the last four years. The main customers for online stores that sell fentanyl or substances to make synthetic drugs are in North America, the region where consumption is highest. But there are also million-dollar cash flows from Europe, Asia, Oceania, Latin America and Africa, according to the regional breakdown by Chainalysis. The company, however, doesn’t have access to the purchase orders and cannot know for sure if all operations are related to the fentanyl trade. Another verification strategy may be to track the purchases of precursor chemicals from laboratories in other countries, or the sales of commonly-used chemical products in the manufacturing of fentanyl.

Elliptic, for its part, has detected $27 million in transactions being made to more than 90 Chinese laboratories that have been identified as collaborating with the cartels. Researchers affirm that the cash flow has increased by a rate of 450% year over year – a reflection of how the trafficking and consumption of fentanyl has skyrocketed. To put these results in perspective, the company notes that if the $27 million had been allocated solely to the purchase of chemical precursors, it would be enough to produce $54 billion worth of fentanyl pills at the street price.

The paradox is that these estimates are possible because the operations are traceable. However, the most staggering calculations don’t merely account for the enormous profit margins, but also for the enormous cost in terms of human life. Around 200 people are dying every day from the fentanyl epidemic in the United States, according to official figures.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.