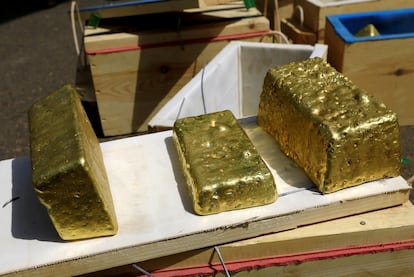

The curse of Sudan’s gold: Why one of the world’s poorest countries fails to profit from vast reserves

The extraction industry is growing and fueling the conflict between the country’s rival generals, as well as aiding Russia’s war effort in Ukraine. But much of it is being smuggled out, depriving the state of much-needed revenue

The rise of gold mining in Sudan, which has become Africa’s third largest producer of the precious mineral over the last decade, has gone hand in hand with the growth of poverty in a country that ranks 172nd in the United Nations Human Development Index (out of a total of 191 nations). While Sudanese authorities announced in January that a record production had been achieved in 2022, the World Bank’s economic indicators pointed to a very different mark for this country located in the Horn of Africa: the percentage of the population below the poverty threshold had risen steadily from 15.3% in 2014 to 32.9% in 2022. That is to say, right now around 15 million people are living on less than $2.15 (€1.96) a day.

Although the gold industry does not explain by itself the impoverishment of Sudan, the battle over its control is fueling the current conflict between the Sudanese army and the main paramilitary organization, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), for whom gold has become one of its main sources of funding. At least 604 people have died and another 5,127 have been injured since a fresh confrontation broke out on April 15, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

No one knows exactly how much gold is being extracted in Sudan. The industry began to gain traction following the secession of South Sudan in 2011, as a way to compensate for the two-thirds of oil wells that Khartoum lost with the independence of the south of the territory. Although available figures are confusing, they do offer a dimension of the mineral’s economic potential. In January, the director of the General Administration for the Supervision and Control of Production Companies, Alaeldin Ali, stated at a media conference that the country had achieved a new extraction record, having exceeded its best production by one ton and 611 kilograms. The previous record was set in 2017 with 107 tons. In other words, last year’s extraction would have been around 109 tons, according to these official calculations. The Sudanese Resources Company announced in April that the export of gold, to the tune of around 41.8 tons, had brought in revenue of about $2 billion (€1.8 billion) in 2022.

None of these figures include the gold that gets smuggled out of the country. “The Central Bank of Sudan has recognized that [mineral] smuggling is a major problem in the country,” says Denise Sprimont-Vasquez, an analyst at the Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS). This expert points to the gold extraction companies controlled by the Rapid Support Forces, led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, Hemedti, as one of the actors responsible for this looting. The other faction, the national army led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, exploits other economic sectors of the country. And then there is the Wagner Group, a shady organization of Russian mercenaries with ties to the Kremlin, whom the United States and the European Union accuse of exploiting Sudanese gold through shell companies. In January of this year, it was revealed that three Russian citizens had been arrested for smuggling gold out of Sudan, recalls Sprimont-Vasquez.

Nor does the Sudanese state have the capacity to account for the gold extracted through artisanal mining methods, which according to the C4ADS analyst represents 85% of the country’s total. “As this activity is mainly informal, it is unlikely that it will be covered by official statistics,” she adds.

The 2021 coup, which ended the transitional government and gave way to the military executive of Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, increased opacity in the gold sector, says Joseph Siegle, research director at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies. During the brief period that Sudan’s transitional government lasted (from the fall of dictator Omar al-Bashir in 2019 to October 2021), an audit by the civilian-led Ministry of Finance revealed that most revenues from gold were not declared. “In 2021 alone, at least 32 tons of gold went unaccounted for, according to state inspections, which is a minimum of $1.9 billion,” Siegle explains. The figure was advanced by CNN in a 2022 investigation. “The estimate that was made is that in 2021 the real production of gold might have reached 233 tons, a figure much higher than what is reflected in the official data,” adds Jesús García Luengo, an expert in sub-Saharan African resources and a member of the African Studies Group at Madrid’s Autonomous University.

Gold as a weapon of war

Gold is financing part of the conflict. “It provides Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo with a deep, government-independent war chest to finance his conflict, even though the Sudanese Armed Forces, led by al-Burhan, also control many companies and economic sectors in the country,” Siegle stresses. Dagalo, according to this analyst, has become one of the richest men in the country, among other things due to his control of the gold sector, in addition to livestock and infrastructure, in the western region of Darfur.

This control of resources by military actors is, says Siegle, an important factor in the current conflict and one of the reasons that keep the country in a critical economic situation. “If the armed forces had to submit to a civilian government, as required by the framework agreement that governed the transition to democracy, then these resources would enter the government treasury, contributing significantly to the economic recovery and stabilization of the country.”

Gold extracted from Sudan is believed to have helped stabilize the Russian economy since the Russian invasion of Ukraine and subsequent international sanctionsResearch director at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies

But Moscow also benefits from this state of affairs. “Wagner, under Yevgeny Prigozhin [known as Russian President Vladimir Putin’s chef] has become very active in the Sudanese gold sector, including in close collaboration with Hemedti,” Siegle explains. According to this expert, it was precisely the arrival of the Wagner Group, whose presence in Sudan Prigozhin has denied, that has raised part of Sudan’s artisanal mining to a commercial scale. “This would explain the record levels of extraction; gold extracted from Sudan is believed to have helped stabilize the Russian economy since the Russian invasion of Ukraine and subsequent international sanctions [against Moscow],” he stresses. According to a CNN investigation published last July and based on information from official Sudanese sources, between February and July of last year at least 16 flights left Sudan for Russia loaded with smuggled gold.

While paramilitary and foreign actors share the exploitation of gold, those 233 tons that are estimated to have been extracted in 2021 would have meant revenues of more than $13 billion [€11.7 billion], notes García Luengo. “This income would be fundamental in a country where the population suffers from severe deprivations, with low Human Development Index indicators and an immense need for basic social services.”

In addition, the scant control over gold mining not only perpetuates poverty, but also represents a major environmental and public health problem. Artisanal miners often use mercury, which is cheaper than other substances, to separate gold from other minerals. During the process, the extracted amalgam is heated, as mercury evaporates before the gold melts. However, it is odorless and highly toxic, so it is easily inhaled by workers, in addition to contaminating land and water.

To measure the impact of this pollution, García Luengo recalls that some two million people work in Sudan’s artisanal mining industry, including children (the country’s population is more than 45 million people). “They work without adequate protection,” he laments, so that the gold business not only impoverishes them and generates violence, but also makes them sick.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.