Sunak in London, Yousaf in Edinburgh: U.K. politics takes on historic ethnic and racial diversity

A new generation of British leaders has altered the political landscape but experts point out the next general election will be the real acid test among the wider public

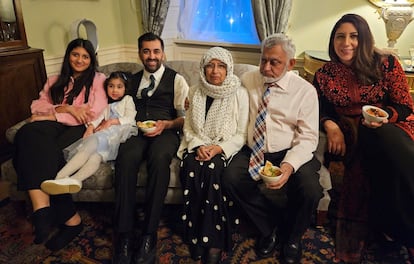

In 1968, British conservative politician Enoch Powell delivered his infamous Rivers of Blood speech in Birmingham, in which he railed against immigration into the U.K. from the Commonwealth countries. Powell was a divisive and controversial figure, even among his Conservative Party peers, but his popularity and widespread public support for his speech highlighted the country’s prevalent attitude toward migration at the time. Little could Powell have imagined that 55 years later, Rishi Sunak, a conservative politician of Indian heritage, would be prime minister and Humza Yousaf, a Muslim of Pakistani descent, would be elected leader of the Scottish National Party and First Minister of Scotland.

However, these historically significant have attracted more interest outside the U.K. than within a country that is in equal parts assimilated by its diversity and uncomfortable with the colonial sins it still carries. “I think all this is very relevant in showing that racial and ethnic minorities want to participate in the future construction of society as much as white majorities. That they can integrate despite continued racism. And that the long history of British imperialism is very much connected to their present identity. Both Rishi Sunak’s and Humza Yousaf’s family history spans South Asia and Africa in its origins. And [Mayor of London] Sadiq Khan’s father was part of a generation recruited to travel to the motherland to work in public transportation,” Nasar Meer, a sociology professor at the School of Social and Political Science at the University of Edinburgh, tells EL PAÍS. “However, most leading politicians in the Conservative Party refuse to acknowledge the forms of institutional racism that blight the lives of Black and other ethnic minorities in the U.K.,” he adds.

A recent independent report on London’s Metropolitan Police highlighted institutional racism, misogyny and homophobia within the force, with multiple instances of female and ethnic minority officers being subjected to bullying and humiliation. Meanwhile, Sunak’s conservative government has presented a draft asylum law designed to prevent anyone arriving in the U.K. in small boats via the English Channel or other unauthorized means from ever legally settling in the country, a proposal that has been widely criticized by NGOs and public figures.

Both matters fall under the remit of Home Secretary Suella Braverman, a London-born politician whose parents are of Indian origin and who immigrated to the UK from Mauritius and Kenya. The current Secretary of State for Business and Trade, Kemi Badenoch, is the daughter of Nigerian immigrants and former Chancellor under Liz Truss, Kwasi Kwarteng, is of Ghanaian descent. The government of former prime minister Boris Johnson was the most diverse in the history of British politics.

“I presided over the candidate selection process for both Kwasi Kwarteng and Suella Braverman. In both cases, I do not remember a single face among those present that was not white,” says Robert Hayward, a former Conservative MP and now a member of the House of Lords and a leading analyst of polls and political trends in the U.K. “And in the case of Kwarteng, who burst into tears when he was informed of his election, there were about 550 members gathered. There are no such prejudices anymore. They do not even come up in the form of private conversations anymore, as they did 10 or 15 years ago, when you would hear phrases like: ‘I’m not sure he’s representative of this constituency,’ which was another way of saying that he wasn’t white.”

What these politicians all have in common is a life and education perfectly suited to British cultural traditions. In many cases, such as those of Sunak and Kwarteng, they have passed through the country’s elite academic institutions. “I think we are more international than other countries, but clearly, you’re not going to move up the ladder if you haven’t been educated in the U.K., giving you a British accent and thus avoiding that barrier that still puts a lot of people off,” says Hayward.

Many Britons reject signs of racism in national institutions and while there is still a collective reluctance to fully introspect over the U.K.’s colonial history, Britain has historically embraced multiculturalism more readily than many other countries.

“I would say that we have been more successful in integrating racial minorities than, for example, France, a country I know well, where the policy is to refuse to acknowledge that there can be differences in status and life perspectives between ethnic minorities and the rest of the population. It is therefore difficult for them to do anything about it. Employment discrimination, for example, seems to be a bigger problem there than it is here,” says historian Jonathan Sumption, one of Britain’s most successful lawyers and a former Supreme Court judge who holds a profound understanding of the conservative soul of many British people. “Of course, there are prejudices, but I think we have adapted relatively well by international standards. Prejudice is mostly based on membership of a particular social class or type of education received, but not on ethnicity.”

Even those most critical of the system have few qualms over acknowledging this historic change: Sunak, Khan, Yousaf, Savid Javid, Kwarteng, Badenoch, Nadhim Zahawi… the political landscape is replete with names defining a new British identity, but some point out that this opening up has, to date, been very much top-down. “Interestingly, neither Yousaf nor Sunak was elected by through the ballot box by British voters. They came to their positions via a closed selection process within their respective parties. We have yet to see if the electorate is comfortable with such diversity in politics. The acid test will come with the next general election,” says Parveen Akhtar, deputy head of the Department of Politics, History and International Relations at Aston University in Birmingham.

London remains the focal point of a cosmopolitan, progressive, and multicultural United Kingdom, a city in which 55% of residents were not born on British soil. But there is still another Britain, one where 81% of the population is white (74.4% of whom are white British) and there are those more inclined to listen to the Enoch Powell that each era creates: 5.5 million people from Asian ethnic groups have integrated into the U.K., as have 2.4 million people from Black ethnic groups. But in the eyes of some, Iraqi, Syrian, Afghan and Albanian refugees, among many others arriving in the U.K., continue to represent the image of a threat.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.