10 presidents of Peru, more than 20 years of instability

With the exception of a couple of interim presidents who held office briefly, the rest of the country’s modern leaders have suffered tragic fates, including jail terms, exile, or death by suicide

Since the beginning of this millennium, almost all Peruvians who have donned the presidential sash have ended up in jail, on the run, dead, or stained by corruption allegations.

In the most recent years, the situation between Congress and the Executive has become untenable. The result: six presidents in less than four years. Dina Boluarte recently became the country’s first female president, after her predecessor – union leader Pedro Castillo – was impeached and arrested for attempting to shut down the Congress and rule by decree. The resulting protests in the South of Peru have resulted in a new, bloody chapter in modern Peruvian history.

EL PAÍS has conducted a brief review of the last 10 presidents of Peru, to give readers a better sense of what has been happening over the last two decades in a country that has seen massive growth and progress, as well as governmental instability and tragedy.

Alberto Fujimori Fujimori

Fujimori took power by surprise in 1990, after defeating the novelist Mario Vargas Llosa in the second round. All polls showed that Vargas Llosa was the favorite.

Of Japanese descent, Fujimori became president with zero political experience. With degrees in physics, mathematics and agricultural engineering from the University of Wisconsin, the University of Strasbourg and the Agrarian University of Peru, he had been a university rector before taking office.

A true outsider, Fujimori was sworn in when Peru was suffering from hyperinflation and terrorism. In April of 1992, he carried out a self-coup with the support of the military, dissolving the Congress of the Republic. The following year – after dismantling the Shining Path Maoist terrorist group – he wrote a new constitution, which governs Peru to this day. A political reform allowed him to win re-election by a landslide in 1995, thanks to his government’s dramatic poverty reduction. However, his victory in 2000 was widely questioned.

In the first months of his third term, in November of 2000, Fujimori – facing daily protests – announced new elections, in which he would not be a candidate. Shortly afterwards, while at a conference in Brunei, he fled to Japan and resigned via fax. He remained in exile in Japan to escape charges of corruption and human rights violations.

In 2005, Fujimori returned to Peru, with the intention of running for a fourth time in the 2006 presidential elections. However, he was arrested while on a layover in Chile – he was subsequently extradited to Peru and put on trial. He received a 25-year sentence for embezzlement, illegal surveillance of political opponents and being aware of the activities of a paramilitary group that combated elements of the Shining Path.

Fujimori received a presidential pardon in December of 2017 on humanitarian grounds, due to his age and fragile health. This pardon was revoked one year later and he was returned to prison. His daughter, Keiko Fujimori, has narrowly lost the presidential elections in 2011, 2016 and 2021.

Valentin Paniagua Corazao

After the fall of Fujimori, Paniagua temporarily assumed the reins of the country in November of 2000, becoming the first Peruvian president by constitutional succession in the 21st century. In his eight months in office, he reformed the judiciary and oversaw a new electoral process.

He ran for president in 2006, receiving 7% of the vote. He died later that same year of natural causes, with no open investigations into his time in office.

Alexander Toledo Manrique

Toledo – Peru’s first Indigenous president – held office from 2001 until 2006. An economist by profession, he oversaw a democratic government with substantial growth. However, his term was marred by corruption allegations and anti-mining protests. Following his term, it would be discovered that he accepted over $20 million in bribes from the Brazilian construction giant, Odebrecht. By then, he was already living and teaching in Stanford, California.

In February of 2017, American authorities detained him. He spent 18 months in jail in the San Francisco Bay Area but was then given house arrest. His extradition process is ongoing.

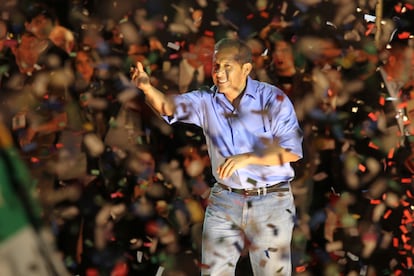

Alan Garcia Perez

Despite having led a catastrophic first government between 1985 and 1990 – which saw a surge in the Shining Path’s terrorism, as well as an inflationary crisis – Peru gave the leader of the historic APRA party a second change to govern between 2006 and 2011.

From 1992 until 2001, García spent nearly a decade in exile in Colombia and France. His oratory led him back to the political promised land. While he moderated his leftist leanings in his second term and significantly reduced extreme poverty, a major social conflict – the so-called “Baguazo” – saw 33 civilians and police officers die in the Amazonas region, due to clashes between Indigenous protestors and mining groups.

García – like other heads of state in the region – was allegedly involved in the Odebrecht scandal. He even sought – and was denied – asylum by the Uruguayan government. While Peruvian prosecutors never managed to prove any charges against him, one managed to secure an order of “preliminary detention” in April of 2019, which would allow the former president to be held in jail for three years without charges. When police arrived at his residence to arrest him, García shot himself.

His death sent shockwaves through Peru and saw tens of thousands of mourners hold a public funeral. Perhaps unlike any other South American politician, he marked progressive politics and the craft of speechmaking for more than three decades.

Ollanta Humala Tasso

Humala was the last Peruvian president to serve the entirety of his term, governing from July of 2011 until July of 2016.

A former soldier, he reached the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Peruvian Army. As leader of the Nationalist Party, he was initially a close ally of Hugo Chávez – his anti-system politics provoked fear from the business community and the middle class, causing him to lose the 2006 presidential elections to Alan García. He subsequently moderated his rhetoric and adopted Brazil’s Lula da Silva as a political model, rather than Chávez. This allowed him to narrowly defeat Keiko Fujimori in 2011.

During his lackluster administration, crime saw an uptick and economic growth was marginal. The Odebrecht corruption scandal also entered the public eye – Humala gave the Brazilian construction giant more infrastructure contracts than any other Peruvian president. Following his term in office, he and his wife – former first lady Nadine Heredia – were charged with accepting illegal campaign donations from the Venezeulan regime in 2006 and the Brazilian government in 2011. Humala and Heredia spent nine months in pretrial detention between 2017 and 2018. They are currently free, but their cases remain open.

Peter Paul Kuczyinski

A Peruvian economist of Jewish-German origin, Kuczynski led Peru from July of 2016 until he resigned in March of 2018. He became president of Peru by a very narrow margin, defeating Keiko Fujimori by less than 42,000 votes out of more than 17 million cast.

Kuczynski had previously been an investment banker, as well as the prime minister and minister of finance under Toledo. While he had the backing of the business sector, he really only won the 2016 elections due to the heavily Indigenous and impoverished South of Peru rejecting Fujimori’s candidacy. He faced hostility from both the left and the pro-Fujimori right – the latter of which held a majority in the Congress. This hindered his legislative agenda.

In December of 2017, PPK – as he is popularly known – was linked to Odebrecht. Investigators alleged that he had taken kickbacks while serving in Toledo’s cabinet. It was also discovered, a few months later, that PPK had negotiated Alberto Fujimori’s humanitarian pardon with Kenji Fujimori, a congressman and Fujimori’s son (Keiko’s younger brother), in exchange for some votes to avoid his impeachment. This revelation sparked fury in the Congress – he resigned just a few hours before an impeachment vote was scheduled in March of 2018.

Just over a year later, the Peruvian Prosecutor’s Office detained PPK for 36 months of pre-trial detention for allegedly engaging in money laundering during Toledo’s administration. Most of this term was served in house arrest due to his delicate health and was extended well into 2022. PPK, 84 – the same age as Alberto Fujimori – is currently free and still awaiting trial, although he cannot leave the country.

Martin Vizcarra Cornejo

Vizcarra – PPK’s vice president – was not popularly elected, but he enjoyed significant public approval during much of his term, from March of 2018 until November of 2020.

According to pollsters, at one point, he reached 83% approval. Of course, like with most Peruvian presidents, this support quickly dissolved.

Vizcarra took over after his boss was impeached. A year-and-a-half into his administration, he dissolved Congress – with the support of 85% of the population – and held new legislative elections.

Vizcarra’s image was distorted when it was discovered that he and select members of his inner circle had received early vaccinations during the pandemic, while other powerful people were being sold vaccines before they were made available to the general public. His harsh lockdowns also damaged the Peruvian economy, while not making a dent in record-high death tolls.

By the end of the first wave of COVID, the new slate of elected representatives impeached him due to alleged crimes of corruption that he committed while serving as the governor of Moquegua, his home region on the southern coast of Peru.

In April of 2021, he ran for Congress and was the representative who received the most votes – 165,000 – but was unable to serve his term, due to being disqualified from holding public office. He is facing up to 15 years in prison for taking bribes.

Manuel Merino de Lama

Merino – who succeeded Vizcarra – didn’t even last a week as president.

As president of the Congress, he was sworn in when Vizcarra was impeached. A member of Acción Popular – a legacy party that last held power in the early 1980s – he had served as a legislator for more than 20 years, facing numerous corruption investigations. From November 10 until November 15 of 2020, he faced massive protests that questioned his legitimacy. These left two students dead and hundreds of police and civilians injured. With intense pressure from civil society, he resigned.

In June of 2022, the Congress exonerated Merino of all political responsibility for the violence that occurred during his five days in power.

Francisco Sagasti Hochhausler

After Merino resigned, Congressman Sagasti – a graduate of the Wharton School of Business – assumed the presidency on an interim basis in November of 2020. Peru was in the midst of both a social and health crisis, with oxygen shortages and low vaccination rates causing the health system to collapse.

During his eight-month-long government, Sagastri tried to reduce the highest COVID mortality rate in the world. The former academic also faced a farmers’ strike and opposition from several blocs in the Congress. However, he managed to leave office with approval ratings hovering above 50%, due to his having completed the purchase and distribution of vaccines. Sagasti, 78, does not have any open investigations – he is widely considered to be a potential presidential candidate in the future.

Pedro Castillo Terrones

The last Peruvian president elected at the polls rose to power after defeating Keiko Fujimori by less than 0.3% in the second round. Running under the Marxist Perú Libre political banner, Castillo – a rural schoolteacher and union organizer from mountainous Cajamarca – became his party’s presidential candidate when the Cuban-educated Vladimir Cerrón was banned from holding public office over corruption allegations.

Unlike Cerrón – the former governor of Junín – Castillo had no political experience. He won over the electorate in the South by promising to change the constitution and push social equity. But after a bitter, tight election, with heavy influence from extremists within his aggrupation, Castillo – Peru’s third Indigenous president, after Toledo and Humala – was never able to govern effectively.

Marred by corruption charges, with several of his family members investigated for embezzlement and bribery, Castillo appointed 78 ministers in his 16 months in office. Resignations were a weekly occurrence – the Congress rebuked several of his appointees, many of whom had no experience in their portfolios. On two occasions, the legislative branch – dominated by centrist and center-right parties – tried and failed to impeach him.

On December 7 of 2022, in a televised address, Castillo took the nation by surprise: he declared that he was shuttering the Congress and “reorganizing” the judiciary. He intended to rule by decree. Within less than three hours, while en route to the Embassy of Mexico to seek asylum, he would be unanimously impeached and arrested. The police, army, courts and most Peruvian citizens opposed this attempted “self-coup” – the conditions of a national emergency simply didn’t exist, despite the low approval ratings of Congress.

Castillo is now serving an 18-month preventative prison sentence, accused of rebellion and conspiracy by the National Prosecutor’s Office. If he is to be found guilty, he could spend the rest of his life behind bars.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.