Inside the coup in Peru: ‘President, what have you done?’

In a conversation with EL PAÍS, the main adviser to Pedro Castillo provides an account of the three hours during which the head of state tried to revert the constitutional order

The speech that Pedro Castillo was going to deliver on Wednesday afternoon in Congress to defend himself from a third impeachment attempt had been edited in a Word file. Luis Alberto Mendieta, the Chief of Staff and Castillo’s main adviser, sent it to the president via WhatsApp.

“President, this is the proposed text for your defense,” said Mendieta’s WhatsApp message.

“Good morning, Don Alberto. It’s not downloading,” Castillo replied.

Speaking to EL PAÍS in downtown Lima in the wake of Castillo’s attempted self-coup, Mendieta says he had suspected that Castillo would not be able to download the document, and that is why he had also printed the speech on paper. But when he tried to personally deliver it to the president’s office, an aide-de-camp blocked his way and assured him that the head of state was busy and could not see him.

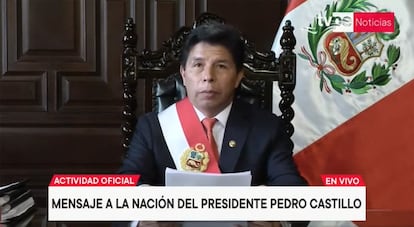

Mendieta, his trusted aide, the one who had been advising him since April to try to straighten out a government adrift, went back to his office to wait for the president to get free again. At that point, someone told him to turn on the television and watch the address to the nation that the president was about to deliver. The adviser went silent: Castillo was announcing a self-coup and a curfew. He, who should have known everything that was going on behind the scenes, knew nothing, according to his own version of events. His first impulse was to go back to see Castillo, who is currently being held in preventive custody while he is investigated for alleged “rebellion and conspiracy.”

Mendieta says that when he got there, he found a man in shock, still sitting in the same chair from which he had just announced the dissolution of Congress and the installation of an emergency government. He was pale. It was not the image of a self-assured dictator, but of a frightened gentleman. Mendieta said his last four words to him:

"President, what have you done?"

The chief of staff thinks that Castillo did not reply, although he is not entirely sure. He may have muttered something like “it was necessary”; or rather “it was for democracy.” But he can’t confirm it. It was a moment of emotions, not words. There were other advisers to Castillo in the room, sitting quietly to one side, as well as Defense Minister Emilio Gustavo Bobbio. Mendieta asked him what he thought and did not get an answer, either.

The minutes ticked by. Castillo had launched a challenge from which he could emerge victorious as a caudillo with full powers, free of the Congress that had tormented him so much. Or he could lose the gamble and get arrested for attempted sedition. Mendieta and the rest of the president’s habitual aides waited in an adjoining room. There was Aníbal Torres, an old constitutional lawyer and staunch Castillo ally who never left the president’s side.

But the succession of events was dire: all the ministers who had not been informed about the plans resigned; the Ombudsman’s office asked Castillo to turn himself in to the authorities; and the military, in a decisive statement, announced that they were turning their backs on him. Castillo was a political corpse.

The people who were near him in recent months had witnessed his battle with Congress, which he accused of making his presidency impossible. There is some truth in that, although it is not the whole truth. His administration never had direction or purpose. He surrounded himself with people with dark interests, according to everyone who has ever worked with him. There was no indication, however, that he was going to imitate Alberto Fujimori, who in 1992 carried out a self-coup that cemented his power for the next decade. Perhaps, in light of the facts, many people agree that he was very worried about his family, how his children and his wife were suffering.

None of them had gotten used to life in the palace. Not even Castillo himself, who often said that he missed milking cows, feeling the fresh grass of the fields and the cold mountain air in the morning. Life in the carpeted corridors seemed artificial to him. He only seemed happy when someone from his village visited him, like the teenager who lived in the United States, for whose grandfather Castillo had worked as a laborer in the fields 40 years earlier. The president comes from a humble family that worked in semi-slavery in the Andes mountain range until General Juan Velasco Alvarado, who was in power between 1968 and 1975, enacted an agrarian reform that gave land to the poorest.

Once the coup failed, those who had been working with him for months began fearing the worst. They couldn’t find the president anywhere. They did not verbalize it, but thought that he could have taken a drastic measure, like former president Alan García, who shot himself at home when a judicial commission was going to arrest him for corruption. The head of Castillo’s security gave orders to enter the rooms where the president lives with his family. There was no one there.

The self-coup had been improvised, but Castillo had prepared an escape route. He was going to the Mexican Embassy after requesting asylum from President Andrés Manuel López Obrador. But he never got there. On the way, he was stopped by his own guards, who took him to a police station. The adventure was over.

Twenty-four hours later, Mendieta recalls it all over tea in a café in downtown Lima:

—As Castillo’s trusted man, do you think he was fully aware of what he was doing?

—In a moment of obfuscation people do irrational acts, but that falls within the field of psychoanalysis and I am not an expert.

On Wednesday night, the president was transferred by helicopter to Barbadillo penintentiary, where Fujimori has been serving his sentence since 2007. Surely that was not what Castillo intended when he began to follow in the footsteps of the last Peruvian dictator.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.