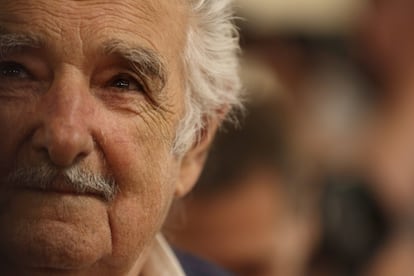

José Mujica: ‘We’re living in a world without political direction’

The former president of Uruguay spoke to EL PAÍS about unchecked transnational interests, the armaments trade and the climate emergency

“The UN’s prognosis is catastrophic. It scares me,” says the 87-year-old politician, referring to the global climate crisis.

Mujica – a former guerrilla who spent 15 years of his life in prison – isn’t a man who is easily intimidated. But he’s shaken by what he perceives as the ineffectiveness of politics.

In an interview with EL PAÍS at his farm on the outskirts of Montevideo, Mujica – who governed Uruguay from 2010 until 2015 – spoke about his wish for greater global understanding and cooperation.

Question. What do you think the pandemic taught us?

Answer. The pandemic revealed many of humanity’s weaknesses. We have the bad habit of appropriating knowledge – not sharing it. With better cooperation, vaccines could have reached more people at a faster rate, saving millions of lives.

Q. Did science fail us?

A. No, science didn’t fail us. Politics failed us. Governments put economic interests ahead of what needed to be done.

Q. During the pandemic, poverty increased dramatically. Today, about 800 million human beings are malnourished.

A. We have a lot of resources, but we’re not using them properly. On one hand, we have lots of people going hungry, but some estimates show that about 25% of foodstuffs get thrown away.

Q. How can society fix that?

A. The responsibility falls on politicians. They know what needs to be done, but they can’t implement helpful policies, because they’re unable to shake the vested financial interests that are behind all of these problems.

Humanity has created a remarkable civilization. We have massive productivity, scientific capacity… but we’re not able to change course. And, you know, many civilizations have failed. Just look at Rome, or the Chinese empire. Globalization is being carried out for the benefit of the market. Politics is secondary, it’s a spectator.

Q. Can politics regain its power?

A. What we need is a global government – one that is heavily scientific and technical– that is respected by everyone. The challenge is that no country wants to give up power or sovereignty.

Q. National interests tend to precede the common good.

A. Yes, exactly! And, funnily enough, with all this talk about sovereignty, there’s a big contradiction. For example, some transnational companies have more power than many states. Especially small states, like Uruguay. We’re living in a world without political direction.

Q. What do you think about the United Nations?

A. We’re ruining the UN. We desperately need a new global accord – a kind of scientific council that can take decisive action.

Q. In addition to progress, there also seems to be a human inclination towards destruction…

A. Humanity spends no less than $2.5 million dollars a minute on weapons and militaries. It’s one of the stupidest things imaginable.

Q. According to Amnesty International, 70% of global arms sales are attributed to the five permanent members of the UN Security Council: Russia, China, France, the UK and the United States. How can we possibly aspire to have peace?

A. Weapons manufacturing has become a tool of diplomacy and influence… the economic strength of armaments drives governments, because there’s such a strong weapons lobby.

We’re in big trouble if this unchecked influence continues. The younger generations need to address ecological disaster, war… they simply have to change the culture.

Q. What exactly does “culture” mean for you?

A. Culture is the repertoire that makes us want to grasp at the fundamental things that surround us and our existence. Culture is a non-material good that helps us to live. Culture is the love of life.

Q. How have you seen the culture change?

A. I’m from a different generation that worshipped rationalism. But all this scientific progress has demonstrated that we humans are more complicated, more emotional. A lot of the time, our decisions are made by our subconscious – we simply find a way to rationalize our emotional decisions. That is to say, first we feel, then we explain.

Q. Where will this take us?

A. I’ve thought about that question a lot. When I was imprisoned and kept in solitary confinement, I often asked myself: What is it that drives us humans?

Q. What answer did you find?

A. We’re social creatures – we can’t live in solitude. For thousands of years, we have lived in groups. In the ancient justice system, the worst punishment – after the death penalty – was to be expelled from the group, from the society. To be exiled.

Q. The idea of cooperation, in a sense, makes us who we are.

A. It has allowed us to create societies. But of course, an individual is still an individual – nature has given us some ego. And this hyper-individualism can lead to conflict. That’s why we are animals that need politics, because the function of politics is to maintain the sense of community despite conflicts. Civilization is the daughter of cooperation.

Q. It’s hard for there to be cooperation when there is so much division. Latin America, for example, contains some of the most unequal societies in the world.

A. Latin America is the descendant of two feudal countries: Portugal and Spain. This has marked our colonial and republican histories. A small upper class owns almost everything.

Q. In the 21st century, can cooperation be a remedy for inequality?

A. The best of capitalism must be maintained. But we still need to build another system of human organization. This will require us to convince the great majority of humanity that cooperation – co-management – is better for us all.

Q. What does it mean to be a rebel in these times?

A. Not following everything that the popular culture tells you to do. For example, some will say that I’m poor, when, in reality, a poor person is someone who needs a lot. Or, as the Aymara people say: poor is the one who has no community. I’m rich because I have many friends and I have enough to live.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.