Betty Ford, the alcoholic first lady who opened rehabilitation clinics for women

She arrived at the White House taking opioid analgesics prescribed for her severe back pain, but her addiction to drugs and alcohol worsened in the following years, as she herself recounted in her autobiography

Betty Ford died in 2011, but her legacy continues to help hundreds of women around the world who, just like Ford herself, suffer from at least one addiction. “As our nation’s first lady, she was a powerful advocate for women’s health and women’s rights. After leaving the White House, Mrs. Ford helped reduce the social stigma surrounding addiction and inspired thousands to seek much-needed treatment,” said former U.S. President Barack Obama on the day of her death.

Ford was the first lady of the United States from 1974 to 1977, during which her husband, Gerald Ford, was the country’s 38th president. She arrived at the White House taking opioid analgesics prescribed for her severe back pain, but her addiction to drugs and alcohol worsened in the following years, as she herself recounted in her autobiography.

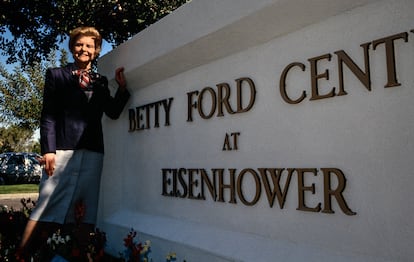

When she was 60 years old, her daughter Susan Ford, upon seeing the severity of her mother’s addiction, organized an intervention with members of the immediate family and doctors with whom Ford had discussed her drug problems. She was admitted to the Long Beach Naval Hospital, where she was interned for months. Ford was always very open about her condition. The frankness she displayed in speaking about her problems was revolutionary at the time: a first lady who acknowledged having abused alcohol and drugs. “Hello, my name is Betty and I’m an alcoholic,” Ford shared when she participated in support groups. Following her recovery, in 1982 she founded the Betty Ford Center in Rancho Mirage, California, one of the first addiction treatment centers designed for women. Today, it continues to set global standards for addiction therapy.

The Betty Ford Center was based on fundamentals that have since been adopted by other clinics around the world, which have followed her legacy in treating patients with a gender-based perspective. Such is the case at the Oceánica clinic in Mazatlan, Sinaloa, Mexico. The site is a private clinic that specializes in addiction rehabilitation, codependence and other mental health conditions. Oceánica was founded in 1991 by Jesús Cevallos Coppel in his search for the world’s most successful treatment model for alcohol and drugs. At one point he made contact with the Betty Ford Center, with which he established an alliance that lasted for more than a decade. “Cevallos was also an alcoholic, like Ford, and that very much motivated him to want to help people to fight their addictions, like they had done,” says the Oceánica Clinic’s director, Mario Gerardo.

So much so, that Ford herself attended the opening of his rehabilitation center in 1993, accompanied by her husband. The facility’s protocols were largely based on the services offered by the Betty Ford Center. “We often traveled to the clinic in California to receive training on new advances in patient treatments, in order to implement them at Oceánica,” Gerardo recalls.

Ford’s techniques are based on those of the Minnesota model, which consists of therapy guided by the 12 steps of Alcoholics Anonymous, and is used to treat a variety of addictions, including substance abuse and alcohol use disorder. This multidisciplinary approach has subsequently been emulated around the world. “In this model, addiction is seen as a disease. A treatable, but not curable disease,” says Gerardo. Doubtlessly, what makes these rehabilitation clinics unique is that their treatments are designed with a gender-based perspective: “Programs are divided by gender and age,” state sources from Oceánica.

In his clinical experience, Gerardo has seen how women differ in the way they acquire and deal with addictions. “The basis of addiction in women is very different to that of men, much like their consumption patterns and specific drugs of abuse.” In addition, the majority of women who come to the center have silent addictions, because they cannot reconcile themselves with being exposed to societal stigmas. “They brush off the fact that they have an addiction and try to hide it. Sometimes, their own family asks them to stop using and to keep quiet about it. Additionally, they deal with much more guilt about leaving home for treatment than men do,” sources from the clinic say.

In Spain, different rehabilitation centers have come to the conclusion that there is a need for a place that specializes in addiction treatment for women. “Traditionally, there has been an inequality gap that not only causes the biopsychosocial particularities of addicted women (of whom 84% are also abused women) to be ignored, but also those of the LGBTQIA+ community, which has its own consumption patterns,” says the director general of the Guadalsalus Group, Luis Rebolo. At his rehabilitation center located in Sevilla (south Spain) they were able to recognize that some clinics were not safe spaces for women. “For many women, the origin of their addictions come from traumatic events or anxieties related to sexual abuse or physical violence they have suffered,” says Rebolo. Less than two years ago, the idea was born from these observations to create a facility with a gender-based perspective, where a safe space for women could be formed.

This is why they operate two facilities: one for men and one for women, where the trans community is also welcomed. “Sometimes it’s easier to rid yourself of a drug addiction than your abuser. We recognize the differences in consumption patterns between genders, just as we do the particularities of physical, psychological and social consequences. Our model of therapeutic intervention with a gender-based perspective adjusts to these differences, leading to more effective results,” says Rebolo.

Another facility that focuses on addiction rehabilitation for women is the Temehi Foundation, which has worked with women who have addictions and who have suffered gender-based violence in the past, since 2016. “It’s common to experience abuse and for that to result in people starting to use substances, because of that mistreatment. There was no place in Spain that was connecting the two,” explains one of the center’s psychologists, Ana García. García adds that “because of social stigmas, it is more harshly viewed when women have addictions, and because of those prejudices it is sometimes more difficult for them to accept that they have a problem. Women suffer in silence, alone, for longer.”

Although they don’t see themselves as following the Betty Ford Center’s legacy step-by-step, they have worked for years to rehabilitate the woman addict with the same approach created by Ford in the 1980s. In her autobiography, Ford described herself: “I am an ordinary woman who was called onstage at an extraordinary time. I was no different once I became first lady than I had been before. But through an accident of history, I became interesting to people.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.