Ovarian reserve tests: Fraud, or useful tool to get pregnant?

Several researchers advise against these tests for women without a history of infertility, although they may be useful in other cases

Raquel García Chico wants to be a mother. At the beginning of 2023, at the age of 29, she underwent an ovarian reserve test. The results were not what she expected: “I saw that it was low, and I thought that I would not be able to have children. I spent several days crying, devastated.” That is, until she spoke to a specialist. “He explained to me that the test did not assess the quality of my eggs,” she recalls, relieved.

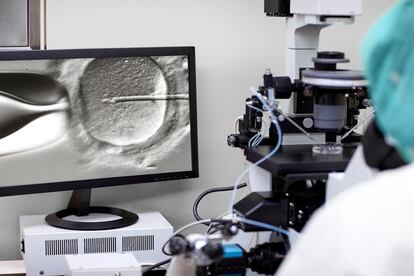

The test that García took, along with two other friends, is called an anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) test, and involves a blood extraction. One can find an abundance of these tests for sale online, promising to reveal the quality and quantity of a woman’s ovarian reserve and measure their “levels of fertility.” One site refers to it as an “essential test for any woman, as it will allow her to make decisions about when to start motherhood.”

But in reality, there is research that indicates that these tests may be useless for some people. A study published in the journal JAMA concludes that for those trying to conceive naturally, a decreased ovarian reserve is not associated with infertility; the authors warn that women should not use anti-Müllerian hormone levels to assess their current fertility.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) takes a similar position, emphasizing that this test should not be used to counsel fertile women “about their reproductive status and future fertility potential.” Alexandra Izquierdo, a gynecologist specializing in assisted reproduction and medical director of the Eugin Madrid fertility clinic, insists that ovarian reserve tests do not determine the chances of spontaneous pregnancy in a couple with no fertility problems. “Without a diagnosis of sterility, they make no sense,” she says.

A review published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology explains that the term “ovarian reserve” has traditionally been used to describe a woman’s reproductive potential. “Modern usage of the term pertains to the quantity of remaining oocytes [cells that are generated in the ovaries and can become mature eggs] rather than oocyte quality, for which age still remains the best predictor,” point out the authors. The commonly used markers “are considered poor predictors of oocyte quality,” regardless of what some online advertisements claim.

Having unprotected sexual relations

According to Izquierdo, when a couple wants to become pregnant, it is advisable to have unprotected sex for at least 12 months before performing any complementary tests. This period is reduced to six months in the case of women over 35 or if there is any condition or pathology that may affect fertility. For example, if they have undergone ovarian or tubal surgeries or if they have certain genetic alterations.

In addition to the fact that this type of test does not help achieve pregnancy, “there is a risk that their use will become widespread outside of strictly medical indications,” warns Virginia Engels, gynecologist and human reproduction specialist in charge of the Gynecology Unit of the Pedro Jaen Group, in Spain. There is a possibility of “overtreating some patients, or generating unnecessary distress and suffering.”

The expert, who is also a member of the Assisted Reproduction Unit of La Paz University Hospital, in Madrid, mentions the following scenario: “Imagine a young couple, both 29, who want to start looking for a pregnancy now. Without a clear indication, the woman does an AMH determination and it comes out somewhat low. In principle, this is not an absolute indication that an assisted reproduction technique is necessary.” In this case, it would be advisable to “try a spontaneous pregnancy as soon as possible, because the patient may have few eggs, but they are expected to be of good quality.”

When are these tests useful?

But then, in which cases are ovarian reserve tests useful? “They constitute fundamental biomarkers to predict how likely it will be that a couple with infertility problems will achieve a pregnancy through assisted reproduction techniques,” explains Engels. The anti-Müllerian hormone test is used, for example, to determine what dose of fertility medicine a patient needs, according to MedlinePlus, the online information service of the United States National Library of Medicine.

This test can also be helpful for people with symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome (irregular or missed periods, acne, hair loss or weight gain) or who are being treated for ovarian cancer, explains MedlinePlus, which highlights that the test can determine if the treatment is working or if the disease has returned.

Increasingly older mothers

When it comes to getting pregnant, the experts consulted assure that the determining factor is age. “At 25, the probability of spontaneous conception per month is around 25%, but after age 40 it drops to 5%,” says Izquierdo. This could be a problem, considering that in many countries women are getting pregnant at increasingly advanced ages.

“Sometimes women find that it is not always possible to combine their pregnancy intentions with the ideal social, work or relationship moment to look for a child,” says Engels. This rise in maternal age leads to “an increase in sterility problems and, therefore, in births resulting from assisted reproduction techniques.”

Those who freeze their eggs before age 34 are more likely to become pregnant with them. The expert explains: “It seems prudent that around that age, women who cannot plan a pregnancy in the short or medium term consider the option of freezing their eggs to have more options to achieve it in the future – without this constituting a guarantee of success.”

Getting pregnant is a complex process that involves many factors, both for women and their partners. The ACOG notes, for example, that men’s fertility also declines with age, although “not as predictably.” Informing the population about human fertility is essential “because ignorance can lead to making wrong decisions,” states Izquierdo. “Just as there is information in schools about the prevention of unwanted pregnancies, they should also teach about how and when is the ideal time to achieve a pregnancy,” she concludes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.