Sun, sand and fertility tourism: Spain becomes the world mecca of egg freezing

More and more women, including many Americans, are traveling there to undergo a procedure known as oocyte vitrification due to the high cost of doing so in their own country

There are those who receive gifts for their wedding. Kaia Nathalie Klaumann decided to give herself a present for her divorce. At 38 years old, with her life collapsing, she thought it was time to freeze her eggs and her life project. But buying time costs money. Doing it in Texas, where she lives, costs exactly $20,000. So after a Google search and a call to a friend, she decided that her gift to herself would be double: egg freezing and a vacation in Spain, where the same procedure costs around €4,000 ($4,274).

Kaia asked for two weeks off from work and caught a plane. “It’s something that’s quite common,” he explains in a telephone conversation. “Many American women travel to Spain to freeze their eggs.” And there are more and more of them. According to the market research company Grand View Search, the global fertility tourism market is expected to grow at a rate of 30% in the next seven years, to reach $6.2 billion by 2030. And on the world map of this booming business, Spain is marked in red letters.

“First of all, it is because of the price,” says Klaumann. “It is also true that I am eight hours by car from Mexico. But of course, Spain has a good reputation, and it is one of the countries where there is the most research on the subject.” Furthermore, Klaumann had lived in the coastal city of Alicante for several years, so she was already familiar with the country. She did not need to resort to the numerous intermediary companies that organize these trips for American women.

One of these companies is Milvia. “Spain is a wonderful tourist destination,” explains its director, Abhi Ghavalkar, by email. “The warm climate, the option of being next to the beach and the possibility of exploring a new destination (sometimes while on vacation) are attractive to American women,” he points out, while also emphasizing that the country “has some of the best fertility providers in the world” and that “treatments are offered at a very competitive price.” Spending a couple of weeks full of hormones seems less unpleasant if you spice up the plan with a walk along Las Ramblas, a visit to the Prado Museum or a day lounging in the sun on a Mediterranean beach.

According to the latest data from the Spanish Ministry of Health, of the 127,420 cycles carried out during 2020, 12,171 were for foreign patients. This is something confirmed by Erin Moore, who worked for seven years as a translator at a fertility clinic in Alicante. “Many women came from England, the Netherlands, Italy and the United States,” she explains on the phone. The treatments last several weeks, so patients have to stay in the city for a while. “And there I was. I helped them find good hotels and restaurants to improve their vacation.” The average health tourism traveler spends €1,082 ($1,156) per week, according to a 2022 analysis by the Spanish Statistics Institute (INE). In the case of vitrification, the expense can be even higher, as the procedure is relatively simple and not particularly painful, and therefore easier to integrate into a vacation.

The warm climate, the option of being by the beach, and the chance to explore a new destination are attractive to American women. Additionally, treatments are offered at very competitive pricesAbhi Ghavalkar, director of Milvia

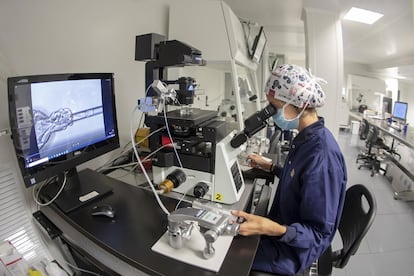

Oocyte vitrification is “an ultra-rapid freezing of eggs in their earliest phase,” explains Sara López, a gynecologist and author of books on the subject. The process begins when the patient is injected with hormones that order the ovaries to release all possible eggs. “So, instead of one growing, the 13 or 15 eggs of the menstrual cycle grow,” she says. Next, there is a small surgical procedure to remove the eggs and put them in liquid nitrogen to preserve them for future use. The once-experimental process became commonplace in 2012. Since then, it has not stopped growing.

In the last decade, the number of women who froze their eggs increased by 142% in Spain, going from 129 cases in 2010 to 5,480 in 2020, according to the most recent data from the Spanish Fertility Society (SEF). The number is now believed to be much higher, as there is some delay in data collection. “Having such a high volume of treatments allows you to carry out more advanced studies,” adds López. “That is why Spain is a leader in Europe, and I dare say that also worldwide, in matters of assisted reproduction.”

Spain was placed on the international map thanks to egg donation. “It continues to be the most important sector within this market,” explains Anna Molas, a postdoctoral researcher in Health Anthropology at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. Many women go to the clinic when it is too late to freeze their own eggs and this is the only alternative. The expert points out that there is an age and class bias in this practice, which she sees as problematic.

Another factor that has helped put Spain on the map is its legislation, which is more lax than in surrounding countries. “Here in the private sector there is no age limitation like there is in other countries. Nor are there hurdles for being a single woman, or a woman married to another woman. And also because of the anonymity [in the case of egg donation] which is no longer the case in most countries.”

Freezing eggs means pushing forward the biological clock, putting the decision to have kids on standby until you have enough economic, work or relationship stability. That’s what happened to Klaumann, who couldn’t find a stable partner or a job she liked. “Also, my desire to be a mother did not awaken until I was at least 35 years old. I was too busy living and enjoying my freedom,” she admits. Hers was an individual decision, but like all decisions, it was conditioned by her social background.

A woman’s eggs begin to lose quality at age 35, explains Antonio Urries, a biologist specializing in assisted reproduction and president of the ASEBIR association. Initially, patients’ eggs were only frozen if the women were undergoing radiotherapy, chemotherapy or removal of the uterus. “But its use has changed, it has progressed. In recent years, there has been a very significant increase due to age issues.” In this sense, the expert emphasizes the importance of educational work. “When a woman is considering her life project, just as she thinks about where she is going to live, and what job she would like to have, she should also consider her reproductive project.” Urries also underscores that this technique “is not a guarantee, it is an opportunity,” as it is not 100% effective. “It is very variable, and we cannot talk about a specific percentage. In 2020 there was one pregnancy for every 12 or 13 vitrified eggs, but it depends a lot on each case.” Klaumann’s personal experience, for example, does not fit into this statistic.

A medical response to a social problem

In 2014, major Silicon Valley companies began offering their female employees the possibility of financing egg freezing. Some critics said that this work incentive concealed a clear message to women: prioritize your professional career, postpone motherhood. However, the model has spread; today 20% of large American companies offer it as a benefit to their employees.

“The delay in motherhood hides a productivist impulse,” says Sara Lafuente Funes, an anthropologist specialized in oocyte vitrification. “It is the result of a society that places capitalist productivity at the center of society and leaves care and reproduction on the fringes.” In this context, she adds, egg freezing becomes a medical patch for a social problem, an individual solution to a collective situation. “In addition, it does so by creating another consumer product, turning reproduction into a market.”

Currently, Lafuente is investigating the social impact of this practice in the Cryosociety Project at the University of Frankfurt. “It is not a question of opposing those treatments. They represent progress, I know. But we should question the fact that they are not solving the problem, and that they are also generating inequalities, since not everyone can access them.”

In 2020, Kaia Nathalie Klaumann remarried and decided to start a family. It was time to use her frozen eggs. But the limitations on international travel due to the Covid crisis made her reject the idea of coming to Spain to be inseminated, so she asked for them to be sent to Texas. It was not a good idea.

The shipment was held up for a year due to bureaucratic and legal obstacles, and when she finally managed to have her eggs shipped, the logistics company lost them. “I used a code to follow where the package was, and I saw it until I stopped seeing it. Suddenly it disappeared,” Klaumann recalls with anguish. “I called and they didn’t know what to tell me, they even hung up on me.” After several days of searching, the package reappeared, but none of the 10 eggs it contained were viable. “No one can tell me the reason for sure, it’s something I can only suspect,” she laments.

Klaumann’s story has a happy ending. His name is Calvin and he is two years old. While fighting to get her frozen eggs, she had also started an in vitro fertilization process at a clinic in Texas, and this procedure was successful. Despite her unpleasant experience, she is a staunch advocate of egg freezing, and even of doing it abroad. Her only regret is that Covid, incompetence and a series of unfortunate events came together to ruin her plan. Like she says, echoing the experts: this is not a guarantee, it is an opportunity.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.