A date at Richard Gere’s house: ‘Life isn’t about money or power, but about love and affection’

EL PAÍS talks with the actor about his career, his life, his social activism, the US president, and the world we live in, from his new home in Madrid: ‘I don’t think Trump was honest with the American people’

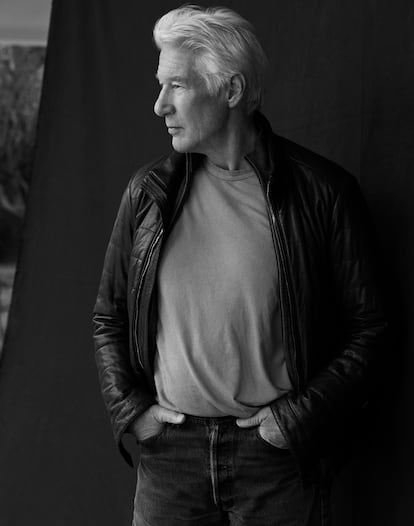

Leave your shoes at the door, please. In Richard Gere’s house — a chalet in the exclusive Madrid neighborhood of La Moraleja — a sign politely asks visitors to leave their shoes in the foyer. When the door opens, the first thing visible is a sort of mudroom filled with coats, boots, and sneakers. That’s where the shoes stay… and so does any fear of a stiff, overly formal interview with a Hollywood star. The meeting had been so hard to arrange that it nearly fell through several times. But once you cross the threshold of that home, the incredibly handsome actor from American Gigolo, the tormented soldier from An Officer and a Gentleman, the wealthy man who falls for a prostitute in Pretty Woman, and the tireless advocate for social causes is no longer just a Hollywood star. Or, of course, not only that.

The spacious and welcoming kitchen, with its terracotta floor and large windows overlooking the garden, is filled with children’s drawings and photos of his children and his wife, Spanish actress Alejandra Gere (née Silva) — the reason the actor decided to live outside the United States for the first time. They moved to Madrid last November. Between them, they have four children, two together and two from previous marriages. And three dogs: two friendly little Cavaliers, Bruno and Bruna, who go everywhere with them, and a fluffy white husky puppy that runs around the terrace between the olive trees and the soccer goals. On the enormous dining room table is a paper edition of The New York Times from that day, April 2, which coincidentally features a major story on the front page about the housing crisis in Spain. The children are at school and everything is quiet and peaceful except for the noise of the construction work being done on the house.

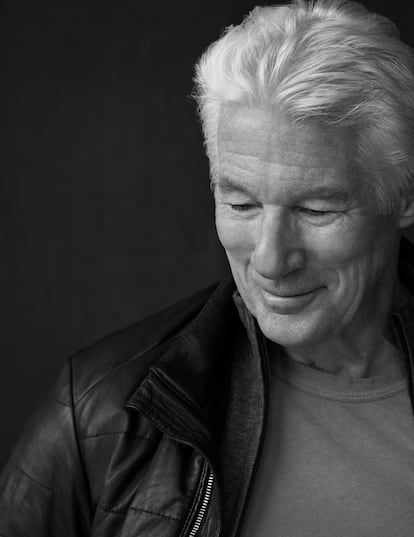

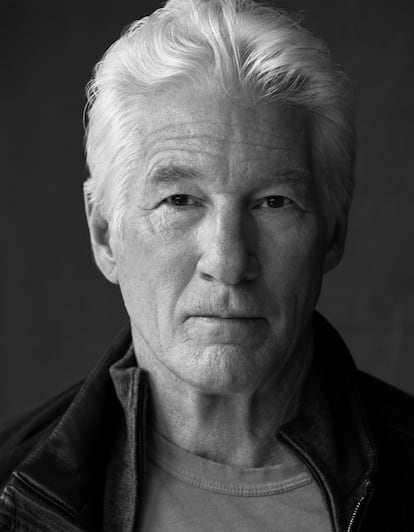

Richard Gere appears just like that, his white hair disheveled, smiling broadly with those small, almond-shaped eyes that have captivated generations of men and women around the world. He’s wearing a worn blue T-shirt and black jeans. When he looks at you, he does so with such attentiveness that you get the feeling he’s scrutinizing your inner self to decide what kind of person you are and whether he can trust you.

“Welcome. We can start whenever you want. Is the room next door okay for you?”

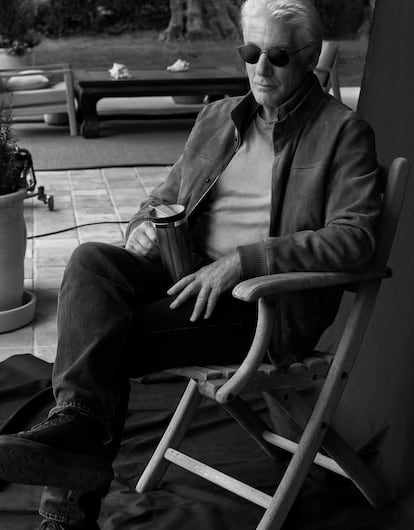

The cozy living room has a fireplace, travel souvenirs, family photos, pictures of Richard and Alejandra with the Dalai Lama, books by John Irving, and a small, round table next to a bright bay window. Gere is a warm and friendly person who carefully reflects on each answer and, despite his packed schedule, generously gives us more than twice the agreed time for both the interview and the photo session. He repeatedly insists that his profession is just another job. One that comes with fame and money (a lot of it), he concedes. “But there’s nothing special about it, and we’re not special beings,” he says. “We’re made of the same stuff as everyone else, and we must always keep that in mind.”

The activist side of his public appearances has become a priority. The heartthrob born 75 years ago in Philadelphia, the person named People magazine’s Sexiest Man Alive in 1999, now has the aura of a good man who will stand up for any cause he believes in.

Question. You’ve been supporting a variety of social causes for decades: Tibetan rights, environmental protection, refugee and migrant rights, and the rights of the homeless. Why do you do this?

Answer. I don’t think there’s any other reason to be alive than to help others. That’s what we’re here for. Helping ourselves doesn’t bring us anything in the long run. I’m an old man now. I’ve seen so much come and go inside myself and in the outer world, and I believe the only thing that truly nourishes the soul is helping someone. That’s why people who spend their lives helping others have such a special energy. Like the team at the NGO Hogar Sí, for example. They impress me immensely. I’ve seen them work incredibly hard in a tiny office with hardly any resources. And now that they’re bigger and have more resources, they continue to give their all to try to end homelessness.

The day before the interview, we accompanied the actor as he and his wife conducted a series of interviews with people who have lived on the streets. They will appear in Lo que nadie quiere ver (What Nobody Wants to See), a short documentary by Hogar Sí — an organization the two have been working with for over eight years. They speak with Pepe, Latyr, Javi, and Mamen, four people with incredibly tough life experiences who tell them about the beatings they endured living on the streets, the pain of feeling invisible and noticing how people turn their heads or cross the street to avoid seeing them, the despair of believing that life isn’t worth living and that they’d be more at peace if they were dead, and the emotion they feel when someone suddenly shows kindness, speaks to them, or offers them a sandwich.

The Geres manage to create an intimate atmosphere from the very start of their conversations with the documentary’s protagonists, and the actor treats them exceptionally well. He listens closely, reaches out, and leans in in genuine interest. His effort to maintain a sense of normalcy is striking in the way he relates to others — despite being surrounded by a team (of women) who manage his schedule, escort him like the star he is, filtering and shielding him… until he’s alone. In those moments, he behaves like the charming next-door neighbor.

Q. You say we’re living in dark times. Certainly that’s the case in the U.S. Why do you think your fellow citizens have re-elected Donald Trump as president after his first term and something as serious as, for example, encouraging the assault on the Capitol?

A. I don’t think Trump was honest with the American people. Some of his ideas were on the table, but not all of them. He said some things he was planning to do, but he didn’t say, “I’m going to take food away from the children of the world, I’m going to take them out of shelters, and take away their medicine.” His attack on the U.S. Agency for International Development or the global health program is incredible. He also didn’t say that the richest man in the world would be his co-president. And, in any case, it wasn’t a landslide victory. He got less than 50% of the vote.

Q. What do you think the people who voted for him think now?

A. I have many friends in the Spanish-speaking community, and some of them openly supported Trump. When we asked them why they voted for someone who said such horrible things about Spanish-speaking people and immigrants, both legal and undocumented, they would say, “Yes, but he’s going to bring down the cost of groceries.” When people don’t have food to eat, ideology is not meaningful to them. In the U.S., we have the richest people in the world and we have the poorest people. And this kind of powerful people thrive on the “I’ll give you more food, if you give me more power, and then I’ll figure out what to do with it” narrative.

Q. This is something that’s happening in many other parts of the world. Trump is a manifestation of a global problem.

A. We live in independent capsules, each protecting our own, acting selfishly and creating conflict. But this way of living is absurd. Those four people I spoke to for the documentary are no different from us. Bad circumstances, perhaps bad choices, but they could be any of us. I believe that at our core, we are all the same. We need to recover a collective sense of responsibility, love, and kindness.

Q. Where does this commitment to collective values come from?

A. My father and mother were pretty extraordinary people. Simple. They both grew up in a farming town between hills and mountains. My father milked cows. They were brilliant people and both managed to study at the prestigious University of Pennsylvania, but they never lost their connection to the land, to the community, to the need to help others. I think my sense of duty to serve comes from that. Especially from my father, Homer, a man always willing to help.

Q. Have you ever felt guilty about your own privileges?

A. I feel grateful, but not guilty. I’m grateful for not having to worry about paying rent or feeding my children, and for being able to choose the projects I participate in. That sense of gratitude never leaves me, and I do feel responsible for giving back, a responsibility I try to approach with humility. I don’t think of myself as better than others, but I believe we should all help however we can. And with kindness, which for me is extremely transformative, revolutionary.

Q. In what sense?

A. If each of us were kind to each other, the world would be different and better. Not all of us respond to wisdom, but we all respond to kindness. Even in the case of Trump, I’m sure there is something kind about him. People say he’s charming in private. Yet the world he’s created around himself is violent, crude, and ignorant. Many of the things he’s doing we’ve never seen before. My parents were Republicans; that was their party. But my father, for example, who fought in World War II and had a very clear sense of right and wrong, would be horrified to see that the president of the most powerful country in the world is a thug.

Q. Are you concerned that Trump’s term could irreversibly change the values of U.S. society?

A. It worries me, yes. Do we want our sons and daughters to grow up thinking that this is the right way to behave, that we have to speak to people this way, treat others this way? Humans have a natural sense of empathy, capable of identifying with other people’s emotions, whether positive or negative. We’ve had this ability since we were children. But, somehow, Trump is cut off from that.

Richard Gere speaks about the new reality in the U.S. from a distance. His home is now in Spain, and over the coming months he’ll be in the U.K. filming the second season of The Agency, his first major role in a television series, where he plays the CIA’s chief in London. “I was interested in being able to explore a character over eight or 10 hours instead of just two,” he says of his latest project. “And I really liked the French series it’s based on. Throughout my life, I’ve met people who worked for the CIA, and I’ve always found them fascinating. It’s a very lonely job; they’re people who live between two worlds, who have to pretend to be something they’re not and do things that are probably illegal, probably immoral, but for the right reasons. I find this duality very interesting.”

Q. What do you like about storytelling?

A. That’s what we human beings are: stories. Each one of us is. And every situation is. Your interview is a story. You came to this house, you hadn’t been there before, you sat in the kitchen, I arrived. We met yesterday. And the story can evolve in very different ways: maybe I’m in a bad mood and don’t want to do this, and you start to feel it and think: how am I going to deal with this person? Or maybe I’m at ease, and then everything goes a different way. Life is about stories. Each one of us writes ours as we live them. And fiction, when it’s good, when it’s true, tells us about our stories, about who we are and what we feel.

Q. Why did you choose to become an actor?

A. I don’t know if I chose it. Sometimes I still wonder what I’m going to be when I grow up... [laughs]. I don’t know. I knew I wanted to do something creative. I had a vague idea that I was going to be a philosopher, poet, musician, actor... I wanted to do something in the realm of feeling, creativity and expression. And through acting, you can do all of those things. You can express all aspects of the human condition.

Q. What does acting mean to you?

A. Exploring. Just that. Exploring and playing. When it loses a feeling of childlike play, it loses its power. When I started acting, I was 19. I didn’t think I’d still be doing this at 75. But I’m still amazed by the scripts I get. They interest me, they entertain me. I read something and think: Wow, yeah, that sounds like fun. So I keep playing.

Q. What was your first role like?

A. In second grade, I played Santa Claus. My mother made the costume and gave me a cotton beard. I was seven years old, and I remember it as a triumph [laughs].

Q. And how do you remember the moment you became a star — when, after American Gigolo, you suddenly turned into a global sex symbol? How do you deal with something like that psychologically?

A. Things changed suddenly, but it’s not a big deal. I’m a worker. Just like everyone else. Just like the bricklayers out there working construction. My job is to make movies, to say a few words on screen, but I’m still a worker. And I don’t take being a star seriously. I never did. Look, my oldest son is just starting as an actor. I think he’s very good and is starting to navigate agents, managers, and so on. I tell him: “Forget all that. The only solid thing is that you know how to act well and work with good teams.” That’s what life is about. The rest is just dancing. It’s okay, but it’s just colors.

Q. And how do you manage not to lose your head amid all the fanfare?

A. It’s a challenge, but like so many others. For me, fame is empty; there’s nothing there, it never interested me in the slightest. I remember a moment from my early days. It was the late 1970s. I’d made several films in a row, but they hadn’t been released yet: Looking for Mr. Goodbar, Days of Heaven, and Yanks. Suddenly, one day, all three of them happened to be in the same theater on Third Avenue in New York. I saw myself three times over. That day, I realized something had changed, that I was no longer just another working actor, that I was somewhat of a commodity. And it scared me. I didn’t think: “Hey, here I am, everybody.” If anything, from that moment on, I went back into myself and became more quiet. I pulled back.

Q. Have you ever had problems with your ego?

A. I’ve never thought I was particularly special.

Q. You started working in Hollywood over 50 years ago. What has changed regarding the role of women? How have you experienced this evolution?

A. There are more women directors and producers now, but for me, they’ve always been my equals. Although it’s true that I’ve never asked how much the other people I worked with were paid, whether they were men or women, and there could be inequalities there.

Q. What do you think about the #MeToo movement?

A. There have always been people who abuse their power. What we didn’t know was the magnitude of some behaviors. I never saw serious abuses in my professional environment, but this has come to light, and it’s clear that there have been very powerful people — whose names we all have in mind — who have used their power to create unequal situations. That’s why it’s so important to have movements like this one that give a voice to victims and help raise awareness to change things. That’s what it’s all about.

Q. A lot has changed in how Hollywood portrays romantic relationships between men and women. Julia Roberts, for example, said that Pretty Woman couldn’t be made today. Do you agree?

A. I haven’t seen it in a long time, but I think I would still find it charming. It’s a film that relied heavily on the chemistry between the director, Julia, and me. I don’t know what I would think now about the power dynamics it depicts. Many things have changed in society and in Hollywood over the decades. Perhaps there are aspects of the film that wouldn’t be made exactly the same. Films reflect the societies of a given time, and everything is constantly changing and being reassessed.

Q. What has it been like growing old in front of the camera?

A. When I go to festivals and they show compilations of my films, I suddenly see my life flash before me in five minutes. From when I was 26 to 75. You see how your face, your voice, everything has changed. Faced with that, you might think: Oh, this is horrible, I’m getting older. Or you might think: Wow, what a spectacle. There’s really nothing surprising about getting older. Everything ages. I think we’re mostly afraid of what other people think of our change, of our aging.

Q. Were you ever afraid the calls would stop coming?

A. No. Now I play the role of an older, experienced man, not a 22-year-old kid.

Q. Your friend Antonio Banderas said that you are too handsome, and that made it harder for you to be considered a serious actor.

A. Is that what he said? [Laughs] I’m happy and grateful for my career. And the truth is, I didn’t think I was handsome; I don’t think anyone does. I don’t know any man or woman who feels beautiful. I’ve been married to very beautiful women [his first two wives were top model Cindy Crawford and actress and model Carey Lowell, mother of his 25-year-old son Homer], but none of them thought that about themselves. It’s always an external assessment.

Q. Let’s just say there was universal agreement about your beauty.

A. When I was young, I didn’t believe it, but it’s true that I recently saw some photos from that time and I did think, ‘My God, he was a really handsome kid!’ [Laughs]. But at the time, I didn’t feel that way. Anyway, I look back at my photos from back then and I don’t know who that person was. That kid doesn’t exist anymore; he’s become something else. Nothing remains the same; everything is constantly changing.

Q. Part of your personal transformation has to do with your practice of Buddhism. How did you first come to the religion?

A. I was young, in my twenties, living in New York, and not particularly happy. In fact, I was quite miserable. This must have been in the late 1960s or early 1970s. There was an all-night bookstore in Sheridan Square in Greenwich Village. I didn’t have any money, so I would go to this bookstore and use it as a library. I would read entire books all night instead of paying for them. The people who worked there were very nice and let me. The first books I read about Buddhism were from Japan. Then I moved on to books about Tibetan culture. I began to meet teachers who were very important to me, to delve deeper into Buddhism, and to have the impulse to travel to Tibet. I had a friend who was writing about the Tibetan people, and he told me to go to Dharamshala, India, where the Dalai Lama is in exile. I went there, met him, and that trip clarified what my voyage would be.

Q. In what sense?

A. I think I was fortunate that all of this came at a time when I was ready to begin to surrender and give up preconceived ideas and my ego. And for the past 45 years, I’ve continued to study and deepen that path. When the Dalai Lama is asked what Buddhism is, what his religion is, he answers, kindness. That’s what I believe in, as I was saying before.

Q. A documentary you produced, Wisdom of Happiness, has just been released in Spain. In it, the Dalai Lama shares his worldview over 90 minutes. Why did you decide to take part in it?

A. Initially, the documentary was primarily intended as a celebration of the Dalai Lama’s 90th birthday in 2025 and his revolutionary vision of emotions, human psychology, and the best way to live in community. When Trump came to power, it took on a new meaning. The world is going in the wrong direction, but the chaos we live in can be transformed, and human beings can improve individually and socially.

Q. Has Buddhism changed your life?

A. Each of us creates our own world. Experiences don’t come from outside, but from within. And each world we live in is our own story, a personal creation, a film we’ve written, directed, and filmed, in which we’ve cast ourselves as the star.

Q. In your personal film, what have been your greatest moments of happiness?

A. My kids, for sure. There’s nothing comparable to when a child is born and you pick them up and look into their eyes. I remember when my first child was born. I was the first thing he saw. Suddenly, I saw in his eyes all the lives we’d spent together, I saw the vastness of the universe in him, I saw everything in that instant. What happiness. What an incredible feeling. You can’t love another adult the way you can love a child. In adult relationships, we always expect something in return for what we give. With a child, you have no expectations. It’s just about giving them love and care.

Q. You’ve found a deep connection later in life.

A. The first time I saw Alejandra, it was all there, I felt it. Our paths were crossing at the right moment. It wasn’t like that for her, who took longer to get there, but it was for me. Everything came together, everything fit, everything was right, there was no dissonance.

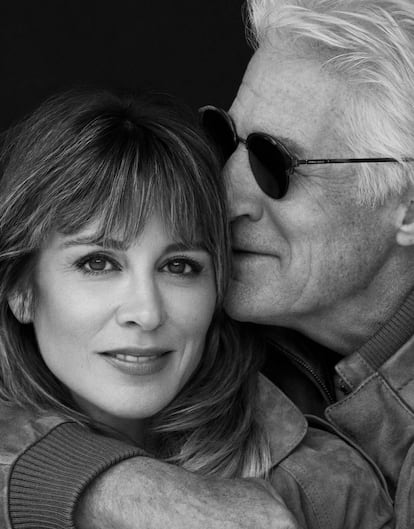

When Alejandra and Richard are together, sparks fly. She is a stunning 42-year-old woman, born in Galicia and raised in Madrid. They met at a hotel in the Italian city of Positano that Alejandra had opened with her former husband, with whom she has a son, Albert. The house had once belonged to film director Franco Zeffirelli. It was 2013. They were introduced, and Gere took her hand and led her to a terrace overlooking the dramatic Amalfi Coast — and it was there that he felt something like a prophecy. Alejandra, 33 years his junior, of course knew who the actor was… but she didn’t know much about his life or career. She hadn’t even seen Pretty Woman.

“I was separating; it was a moment of great confusion for me,” she recalls of their beginnings. “I noticed a special connection, but at first I preferred to remain friends. Little by little, I realized how complementary we were, how good we were together. But we did everything carefully and slowly, step by step. We waited to live together, to have children [they have two together, Alexander and James, aged six and five]. Everything has been very intense but at the same time very calm and natural. I honestly don’t even notice the age difference. He has much more energy than I do [laughs].”

― What’s it like living alongside someone as globally famous as Richard Gere?

“Perhaps from the outside it might seem like it’s difficult to maintain a normal life, but it hasn’t been that way at all. We try to stay under the radar, and I think we’ve succeeded unless we have to attend a promotion or public event for the NGOs we work with, which is another point of great common interest and one of the main reasons we moved to Spain. The rest of the time we’re mostly at home. Alone, or with family, or with our close friends. We don’t have much of a social life. Neither of us likes to be at parties all day. We’re very homey. In fact, Richard could have easily welcomed you in slippers.”

― Do you plan to live in Madrid for a long time?

“We really like Madrid, and we’re going to stay here for a few years. We’re very happy. It’s a city that has changed a lot, with a very special energy, it feels like it’s smiling. Our children’s school is now here, along with their friends, the foundations we work with, Hogar Sí, Open Arms… We’re both completely dedicated to helping end homelessness in Spain. Without a roof over your head, it’s very easy to lose track of time, self-esteem, and job prospects... and breaking out of that cycle without a home is complicated.”

Twelve years after they first met, he still doesn’t take his eyes off her when they’re together. He watches and listens to her with a mix of admiration, devotion, and respect. During the photo shoot for this interview, while they were posing on the porch, he leaned in and kissed her passionately on the lips several times, making her and the photographer laugh. “I’m going to make the most of having her this close for so long,” he said.

Q. What does love mean to you?

A. For me, love between a man and a woman is trust. If you can trust someone, through that person you also trust the idea of yourself, who you are. And that’s an incredible gift you can give someone. To truly say: I’m here, I see you, you can trust me.

Q. Is this your first time living outside the United States?

A. Yes. I’ve been to many places around the world, but this is the first time I’ve moved and taken everything with me. I’m trying to make this the same as every place else I’ve lived. It’s important I have my office, my piano, my guitars, my books, which are always with me... In a way, I’ve taken my world and put it here. Alejandra gave me six or seven years in the U.S.; she dropped everything to be with me and create a life together. But I could see it was important for her to come back, that she really missed her family and friends. She’s blossoming here.

Q. What do you miss?

A. I miss my family and friends. I was just in New York visiting my friends and my oldest son. We went to Pennsylvania, to the small town where my father and mother came from, and we visited their grave. I need to somehow feel connected to my history, to my best friends, to stay in contact with all of it.

Q. Do you think you’ve had a good life?

A. Life isn’t about money or power, but about love and affection, and I’m so grateful to have them around. I realize it’s a gift. We’re social creatures and we need interactions with others. I wake up every morning feeling very optimistic, imagining that everything is going to go well, that wonderful things can happen, and thinking how lucky we are to be alive.

Q. What would you like your legacy to be?

A. Above all, I would like my children to be proud of me. For them to think, ‘My dad was a pretty great guy.’

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition