The ‘dabbawala’ network: A near-failsafe food delivery system that has been feeding Mumbai for a century

Without errors or delays, the ‘dabbawalas’ transport hundreds of thousands of lunchboxes every day, all without the use of technology. Their efficient system has earned praise from business schools worldwide

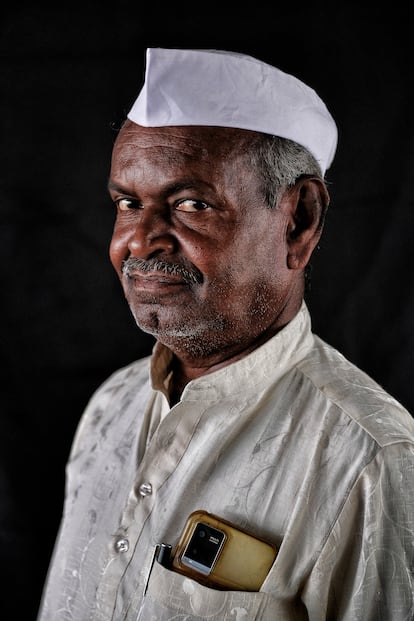

When Mininath Jadhav picks up the first lunchbox at a tenement building in Andheri, one of Mumbai’s most densely populated suburbs, just minutes before 9 a.m., he has already been awake for five hours, and finished his morning job as a milkman, which he does for two hours every morning in his neighborhood. There are still 23 more lunchboxes to collect in Andheri before 10 a.m., followed by another 37 to deliver around 1 p.m. to various offices in Lower Parel, a suburb 12 miles further south, reached by Mumbai’s local trains. At 37, Mininath has been part of the small army of men responsible for feeding over 100,000 people daily in the city for 24 years. These workers are known as dabbawalas and are easily recognized by their traditional white Gandhi caps, or topis.

“In India, a dabba is a round metal box used to carry hot food, and wallah means someone who takes charge of something,” explains Ramdas Karwande, 47, who has been president of the Mumbai Tiffin Box Suppliers Association cooperative since 2023. “We dabbawalas are in charge of delivering lunchboxes of homemade food to the offices of hundreds of thousands of workers, picking them up from their homes a few hours earlier. We’ve been providing this service in Mumbai since 1890, using a system that has earned us several international accolades, including the Six Sigma certification for our high accuracy rate, as we make only one error for every six million transactions,” he adds proudly.

A pleasant scent of spices wafts from the kitchen of 44-year-old Pooja Sanghvi, who tastes the sauce simmering in one of the pots on the stove and adds a pinch of salt. She lives very close to the Dadar train station, so her lunchbox, also called a dabba or tiffin, will be the last one Mahadev Pangare will pick up shortly before 10 a.m. “I’ve been using this service for seven years, and in all that time, they’ve never failed to deliver or arrived late,” says Pooja, looking at the clock on the wall and hurrying to fill the various compartments of the metal lunchbox, which will travel to an office in Churchgate. She knows that she has to finish the mean on time, since meeting deadlines is one of the unwavering principles of the dabbawalas, who work in a synchronized and disciplined manner to maintain their high level of efficiency. A delay on her part could disrupt the entire delivery chain. Therefore, if a customer delivers their lunchbox late three times in a month, their service is suspended.

Five minutes before 10 a.m., Mahadev, 46, who has been working as a dabbawala since he was 16, parks his bicycle loaded with about 20 tiffins and walks briskly up the two flights to Pooja’s house, where she’s already waiting for him at the door with a big smile and a lunchbox in hand. In less than two minutes, they exchange greetings, wish each other a good day, and Mahadev runs off again to his bicycle to make it to the station on time. The meeting point is under the small, graffiti-covered bridge rising over the road in front of Dadar station’s main entrance.

Amid the morning bustle — commuters rushing to catch trains, flower and vegetable vendors setting up their stalls — dabbawalas arrive with their bicycles stacked high with lunchboxes. Mahadev moves between the various stacks of tiffins waiting in a corner of the bridge, leaves Pooja’s lunchbox next to those that will go to Churchgate station, distributes the rest, and heads to the stack of tiffins that will go to Bandra station, where he delivers to, to begin sorting them. His train leaves at 10:38, enough time for the other dabbawalas to finish arriving with the lunchboxes to be delivered to Bandra.

Unlike other food delivery platforms, dabbawalas don’t use any technology. They operate using a system of codes with symbols and colors, devised over a century ago, that specifies the origin, destination, and the delivery people involved in the process. Each tiffin passes through three hands: the collector who picks it up from the customer’s home with freshly prepared food, the transporter who carries it by train to the station nearest the recipient’s office, and the final courier who delivers it. Everything is marked on each tiffin to make handling quick and efficient.

In turn, each tiffin goes through two sorting processes that take place near the train stations: first at the origin station where it was picked up, where it will be placed in different piles depending on the destination station; and the second sorting takes place at the destination station, where tiffins will arrive from different parts of Mumbai and will be sorted again according to the delivery routes.

This process will be repeated in reverse, as dabbawalas also collect the empty lunchboxes and return them to their homes. In addition, there are one or two dabbawalas in each area responsible for covering any delays or incidents to ensure deliveries are always on time.

Dressed in a white shirt, trousers, and cap, Kaluram Parithe, 60, checks that all his tiffins have arrived, ties them together for easy transport, and carries about 20 of them over his right shoulder with the help of a companion. He carries the rest in his left arm and heads toward platform 2 at Dadar station, where he will catch the train to Churchgate, a neighborhood in south Mumbai that is home to a large number of offices, where dabbawalas arrive from all over the city.

Like every day, the train arrives on time, and Kaluram has just 40 seconds to board the luggage car, where he meets other delivery workers from other stations further north. He stands by the door of the small car packed with lunchboxes. With almost no room to move, he joins in the lively conversation of his colleagues, who are taking advantage of the journey to rest and recover their strength. Twenty minutes later, they arrive at the end of the line, and everyone rushes to grab their lunchboxes to take them to the next sorting point.

In front of Churchgate station, hundreds of tiffins are piled up along a 400-meter stretch of sidewalk, where around 30 dabbawalas organize them and load them onto their bicycles under the watchful eyes of tourists and onlookers. Hanumant Chimate, 49, will be delivering by cart. “I have more than 30 dabbas to deliver, too many to carry on the bike.” An hour and a half later, he has delivered all the tiffins on time and parks the cart at the entrance to a pedestrian street. Taking out his own tiffin, packed with the meal his wife prepared that morning, he heads to a nearby building to eat with three fellow dabbawalas who cover the same area.

“We meet every day to eat together,” explains Hanumat, who has been delivering meals for 25 years. Dabbawalas are more than just coworkers and equal partners in a cooperative — they share the same origins, culture, ethical values, and religious beliefs. Like the first dabbawala, Mahadeo Havaji Bachche, who started the service in 1890 after a Parsi banker asked him to deliver food from his home to the bank, almost all of them come from rural areas in the Pune district and belong to the Hindu Vakari community. Vakaris worship the god Vithala, who teaches that giving food is a great virtue; offering food to others is equivalent to offering it to God. Therefore, for many dabbawalas, their work has an important spiritual meaning.

Six train stops further north, in Lower Parel, Mininath Jadhav retraces his morning route to collect empty lunchboxes at One World Center, a brand-new business complex spread across two office towers. It’s home to EverSource Capital, a leading Asian climate impact investor whose CFO is one of the dabbawalas’ satisfied customers. Viral Rathod, 48, has been using this service for 15 years. He has worked at various companies and says they’ve never failed him in all that time. “They’re very efficient and affordable. I pay 1,200 rupees a month (about $13) for the delivery service from Monday to Friday. But above all, they’re very convenient because they save me from having to carry food on the train, which during rush hour is almost an impossible task. And my wife has time to prepare homemade meals, which take time,” Viral explains in front of the imposing building.

Meanwhile, in a more modest office in the same suburb of Lower Parel, 35-year-old Sandip Jadhav collects the empty lunchbox from 54-year-old real estate agent Chetan Vira, a client of four years. “The dabbawalas are an institution in Mumbai; they are humble, serious people who have earned everyone’s respect,” says Chetan. “I have complete trust in them, so much so that when I forgot my wallet at home, I asked my wife to put it next to the food, since I knew it would arrive and no one would open it.”

Around 7 p.m., Mininath returns home to Sagar Khutir, a humble settlement in the Andheri district just a few meters from the sea, where other dabbawalas also live with their families. Mininath lives with his wife and 10-year-old daughter in a small room with no bathroom, measuring about 10 square meters, for which he pays 9,000 rupees a month (about $100). His dabbawala salary of 15,000 rupees ($170) and an additional 5,000 rupees ($55) from his milk delivery job help him cover expenses and send money back to his family in Pune.

“I started working as a dabbawala when I was 13, and I’ll probably continue until I retire,” he says. Like many of his peers, he came to Bombay as a child to help his family and was welcomed by the dabbawala community.

The discipline, organization, and dedication of these men have made their remarkably efficient system a subject of study and praise in international business schools and logistics companies. Their model demonstrates that, with minimal resources but exceptional coordination, teamwork, and a non-hierarchical structure, it is possible to create a last-mile distribution network — referring to the final stage of product delivery — so efficient, affordable, and sustainable that no one has been able to surpass it.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.