WhatsApp: The new weapon in the fight to win over Spanish voters

Ahead of the general elections in Spain on April 28, political parties such as the PP and Vox are turning to the instant messaging service in a bid to reach a wider audience

During the run-up to the last general election in Spain, political parties used Facebook, Twitter and Instagram to spread their messages. This year, with a snap general election called for April 28 and local, regional and European elections set for May 26, it appears they are turning to WhatsApp, the most popular social network in Spain.

Political parties know that people increasingly place more trust in people and less in institutions

Author Antonio Gutiérrez-Rubí

“We’ve been working with WhatsApp since 2014,” explains Juan Carro, the national communications secretary for the conservative Popular Party (PP). “First we created groups with members. Then we went for the volunteers.” According to Corro, today the party has “thousands” of subscribers, who exchange ideas, photos and videos.

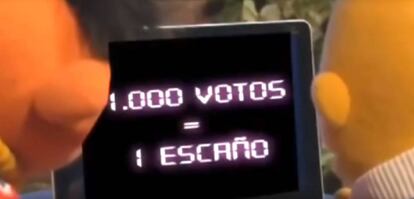

In one recently shared video, Sesame Street character Bert reads the newspaper: “Don’t you realize Ernie, if you vote for Vox you are helping [Prime Minister] Sánchez and the Catalan separatists?” The clip, made by an anonymous user, explains Spain’s D’Hondt proportional representation system, according to which some votes carry more weight depending on where they are cast.

“It’s magnificent,” says Carro. “The video simply illustrates a law that is complex to understand. We didn’t make it ourselves but we saw it and quickly shared it on WhatsApp.”

The “Bert and Ernie” video shared by the Popular Party (Spanish audio).

The message reached people who had never voted for the PP before.

According to the latest report from the Spanish Digital Communication Association, the average Spaniard spends more than 90 minutes a day reading and replying to messages on WhatsApp. This has turned the instant-messaging service into an important tool in the fight to win voters. Most WhatsApp users are in at least 10 chat groups and 70% of users turn to the application to speak with family and friends for no specific reason, according to the most recent survey from the Center of Sociological Research (CIS).

“Political parties know that people increasingly place more trust in people and less in institutions,” explains Antonio Gutiérrez-Rubí, the author of the book La política en tiempos del WhatsApp (or, Politics in the time of WhatsApp). The main advantage of WhatsApp, says Gutiérrez-Rubi, is that it allows ideas to quickly become viral. “One message reaches the first ring of groups. Then they pass it on to others. And to others,” he added.

The director of the consultancy RedLines, César Calderón, gives an example: “It’s like when a friend recommends a series and you watch it. But if the director tells you to on television, you might not. Today the goal is to appear in the chat groups of families, parents and friends.”

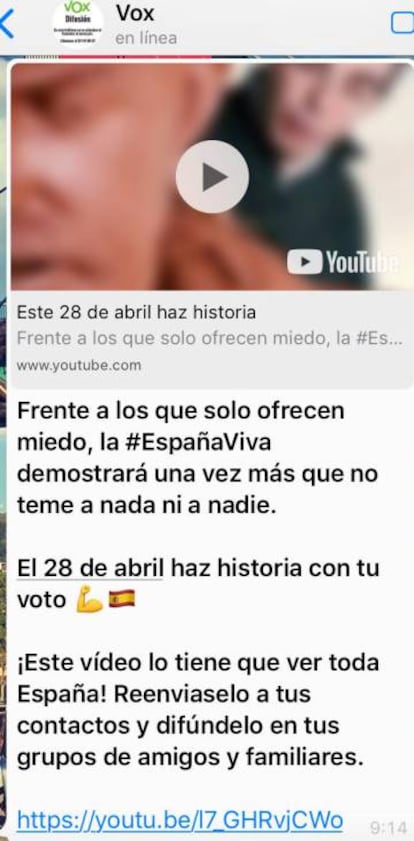

This what the far-right group Vox managed to do ahead of the regional Andalusian elections in December. The party’s social media chief, Manuel Mariscal, told EL PAÍS two months ago that it began recruiting followers in June 2018. “We got 2,000 in a few days,” he said. Vox, thanks in part to its social media strategy, went on to win 12 seats in the Andalusian parliament and continues to surge in the polls ahead of the spring elections.

The method is simple. A supporter adds Vox to their list of contacts. The party organizes these members into lists, with no more than 256 in each. Then with one click, the far-right group can share messages like a video sent on Friday with this accompanying text: “For Spain, forward this video to your contacts and share it in your groups of friends and family.” It is much cheaper than paying to advertise in traditional media.

In February, social media giant Facebook – the owner of WhatsApp – launched WhatsAppBusiness, a tool that allows companies to communicate with their clients. The tool is free to use but there are also private businesses that offer the same service for a fee. For between €600 and €1,000 a month, these companies will allow a political party send out an as many messages as they want to 10,000 people, according to industry sources.

And it’s not just Vox and the PP who are using WhatsApp. Sources from the center-right Ciudadanos (Citizens) party say they also used the messaging service in the Andalusian regional elections. “Now we are looking at if we should use it ahead of the general elections,” party sources say. The Socialist Party (PSOE) of Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez uses WhatsApp but only for internal purposes. “We send messages to federations or to those in charge of social media in the regions,” explains a spokesperson. To reach out to voters, the party uses the messaging service Telegram, where it has 3,000 members.

The anti-austerity Podemos party has a dozen people running their social media team. The party has been automatically subscribing members to their WhatsApp group since August 2018. “We send the same messages here that we share on other social media. This week, 6,000 people have requested to join,” the team said.

Election spam

Four months ago, the Spanish Senate approved a new data-protection law that allows political parties and electoral groups to collect the personal information of social media users during election campaigns. This information is then used to create personalized propaganda, a process informally known as election spam. Thanks to this change, a person can receive unsolicited political messages, without having to add a party’s number to their contact list.

The public ombudsman has called on the Constitutional Court to stop the measure. The Spanish Data Protection Agency (AEPD) has also placed some restrictions on the law. Political parties that want to collect information must submit their request to the agency 21 days before a campaign begins.

For now though, subscribers will continue to receive WhatsApp messages until April 28. “WhatsApp does not directly influence the vote, but it does strengthen it,” says Belen Barreiro, the current director of polling firm 40dB and the former head of CIS. “Today, there is more doubt in the right-wing bloc. This could be the key.”

The far-right Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, for example, won the 2018 elections in his country without hardly ever appearing on television. He didn’t need to; he had the largest number of followers on a smaller screen: WhatsApp.

English version by Melissa Kitson.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.