The children Spain doesn’t want

The Socialist Party government has presented a plan to repatriate underage migrants despite criticism it is crossing a red line

The Spanish government of Socialist Party (PSOE) Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez has announced an emergency plan to prioritize the process of repatriating migrant children because “they are better off being with their families.”

In 2018, around 6,000 underage migrants arrived in Spain, putting pressure on shelters and exposing the shortcomings of the region’s support networks. The government has handed out €40 million to regions in Spain to compensate for the cost of caring for the nearly 12,500 migrant children estimated to be living in the country but has not announced any plans to improve their social integration.

I don’t think what happened to me in my country will happen to me here

Instead, the government has proposed initiatives to repatriate children to their home countries and is in negotiations with Morocco to send minors from that country back.

“There are red lines that no politician should cross, such as proposing the repatriation of girls who have escaped from forced marriages, children fleeing situations of extreme poverty, violence and the impossibility of making a future with the least bit of dignity,” says Lourdes Reeyzábal, president of Roots Foundation, an organization that has been working with children at risk of social exclusion for 20 years.

Some of these children, who did not want to use their real names, say they do not want to go back. “Listening to them is essential if we want to prioritize policies that protect children over controlling our borders,” says Reyzábal.

“Moroccan children fear nothing”

Anass is one of the Moroccan children who sleep near Madrid’s central square, the popular tourist landmark Puerta del Sol. He collects cardboard thrown out by stores and tries to keep warm in a jacket with a missing zipper. When he was 14 years old, he escaped from a center for minors. “They beat me there. I’m not thinking of going back,” he says.

More than a year ago, Anass left his home without telling anyone and with little more than some tobacco in his pocket. His friends, who help translate, agree that it was the right decision. “In Morocco, even if you study, you can’t get a job,” they say. Anass left school when he was 12 and turned into a rebel child. He snuck into Ceuta, a Spanish exclave city in North Africa, by hiding under a bus and two days later made it to Algeciras in the south of the peninsula. “Moroccan children fear nothing,” he says casually.

“I always think that they aren’t going to love me”

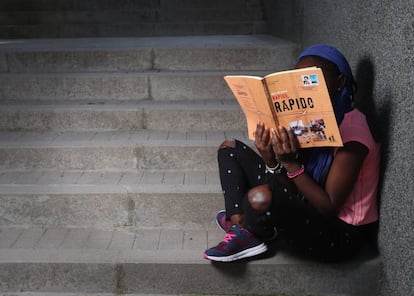

Arcange loves romantic novels. She is charmed by the happy endings and the female characters who are like princesses. But her kind of love story, which forced her to flee Cameroon, never appears in these books. Two years ago, the 16-year-old was told by her parents that she was to marry an older man. The demand, which was compounded by other problems at home, destroyed her.

When asked why she thinks she will not have her own romance story, she replies: “I always think that they aren’t going to love me.”

Arcange, who still looks like a child, fled home thanks to her godmother. She spent a year in hiding in Cameroon and flew to Madrid in August 2017. She used a fake passport that said she was an adult in order to travel without her parents’ authorization. As soon as she arrived, she approached police officers. “I don’t have anywhere to go,” she told them. That day she slept in the airport. Arcange was identified as a minor and a possible victim of human trafficking, although she didn’t know what that meant. Her concerns were about returning home. “I still feel scared but I don’t think what happened to me in my country will happen to me here,” she says.

The system turned her into an adult. After completing forensic exams – criticized for their wide margin of error – Arcange was ruled to be 18-years-old. She was no longer protected. “You have to leave here tomorrow,” the shelter told her. “I cried a lot,” she remembers.

Arcange has been forced to apply for asylum as an adult and is now living with women much older than her. She dreams of going to university and becoming a prestigious economist but says that will never happen: “It’s a very difficult dream.”

“I never did kid things”

In the streets where Mustafá lives, in a neighborhood on the Moroccan border with Ceuta, kids his own age play around. His friends had already left to find a better life and he did not want to grow old in Morocco. “There were five of us in my family, we didn’t have bedrooms and we all slept in the living room,” he explains. “I never did kid things. I stopped going to school when I was 10. I sold clothes in the street.”

When he turned 14, Mustafá warned his mother he was going to leave. She looked up at the sky and began to cry. “She told me not to do it, but that night I didn’t sleep at home.” A few days later he had crossed into Ceuta, where he lived for two years between a children’s shelter and the street. He says it was a nightmare. He was harassed by mafias who wanted him sell drugs. “They beat me up a lot.”

After trying for a month, Mustafá was finally able to hide under a truck and arrived in Algeciras. One week later he was on a bus to Madrid where he was taken in by a shelter in Hortaleza, known for overcrowding and abuse. “They always treated me like a dog,” he says, explaining that he was physically and psychologically abused by the guards. Authorities in the Madrid region say they do not know of any recent cases of violence but Roots Foundation says it has reported attacks against numerous children. In December, after sleeping on the street for months, Mustafá turned 18 in a juvenile detention center. He was sent there for aggravated theft, a crime he says he did not commit, and that is yet to go to trial. In all the years he was in shelters, he did not receive more than a fishmongers’ course. His dream is to be able to send money back to his family.

“I have grown up on this journey”

Ibrahim lost his mother in an accident when he was only two years old and his father, to illness, four years later. He does not remember what his family life was like in Guinea. “I feel very lonely,” he says. Ibrahim left school when he was seven years old because he didn’t have enough money to go. At 13, he decided to leave without telling anyone. He crossed over Mali in a truck and arrived in Algeria, where he worked as a laborer for a year. He says he wasn’t a slave but he slept on the site and his bosses stole his wages. “I don’t know why but we, black people, were treated badly.”

In 2018, around 6,000 underage migrants arrived in Spain

Ibrahim arrived in Spain via the exclave city of Melilla in North Africa in 2016. He pretended to be an adult and no one questioned him. “I only wanted to leave there as soon as possible and reach Madrid,” he explains. When he made it to the Spanish capital by bus in 2017 and decided to tell the truth, forensic tests said he was an adult.

Today, in a shelter apartment in Madrid, he wakes up at 6am to go to mechanic classes and hopes to be specialist. He has a girlfriend from Madrid and lots of friends from the neighborhood. He doesn’t complain about anything. “I have grown up on this journey. I have improved my attitude and in my studies,” he says. But Ibrahim’s story, like that of many other migrants, does not end here. “When I can, I will leave for Canada.”

English version by Melissa Kitson.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.