“Bank-owned apartment for sale to squatters. Pay in cash”

Madrid's property black market is offering empty homes to buy or rent for a period of two years – the time it takes the repossession to go through the courts

Sineb, the ‘real estate agent’ does everything she can to make her client happy. She meets her at the metro and together they walk towards a well-appointed building. She then proceeds to show her around a three-bedroom apartment, with a refurbished bathroom, lounge room and kitchen. There is an elevator and plenty of light. No need to pay costs for the maintenance of communal spaces.

“Great,” says the client. “I like it. How much will it cost me?”

“You give me €1,400 in cash and I give you the keys. Easy.”

Quickly and without much ado, they complete the deal – one of many in Madrid’s underground property market for the sale and rent of squatter apartments.

Be they gangs or individuals, there are now a significant number of people making their living by finding empty properties and offering them to house hunters as a cheap two-year measure – the time it usually takes for repossession cases to make their way through the courts.

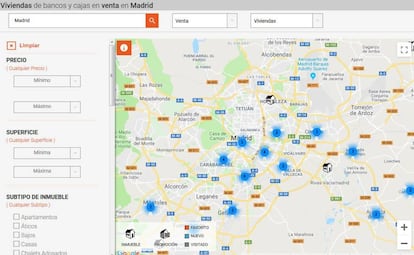

Most of the apartments belong to banks or distressed debt funds that have evicted the previous owners for defaulting on mortgage payments. The ‘realtors’ find the flats on bank websites. They also comb neighborhoods for properties that appear deserted. ‘Buying’ one of these properties for the purposes of squatting costs between €1,000 and €2,000. Renting, on the other hand, costs €300 a month. Sineb had placed an ad on the Spanish classified website Milanuncios for an apartment in Parla for €1,400. “You’ve got electricity and water but you’ll never have to pay a bill,” she explained to the client in person.

The advertisement has a brief description of the property’s history: it was left empty after being repossessed and “a guy” – almost certainly an experts in locks – opened it up. It belongs to Sabadell bank, which sends people round to invite the squatters to leave from time to time.

Then there are three pieces of advice to squatters:

Have children. “The judge will feel sorry for you, which will buy you more time. I tell the bank I am pregnant and that puts the brakes on things. The neighbors will also be more considerate.”

Change the locks. “The former owners might still have keys and so will the bank, so don’t take chances.”

Find an excuse. “If the neighbors ask, tell them you can’t leave the place because you rented it and the owner isn’t going to give you back your deposit.”

When Sineb finishes showing a client around, she uses the same line as all realtors: “There’s a lot of people interested. This one will go fast.”

In Madrid there are 4,717 squatter homes, 1,717 of which are officially protected. But even though squatters almost always move into public buildings or apartments that have been repossessed by the banks, the trend is generating a degree of anxiety among the elderly in districts such as Monte Igueldo and Vallecas, where private homes have occasionally been occupied.

Climate of fear

Mari Carmen Ortega, 72, says she is too scared to go to the doctor for tests in case she is sent to hospital and squatters take over her home. “I am not moving,” she says. “I don’t want to lose my place.” What she is perhaps unaware of is that, in such an eventuality, she would be within her rights to report it as forced entry and the squatters would be made to leave.

But few either know or trust that this would be the case. Instead, elderly neighbors are forming support groups, taking turns to go and buy bread, visit their children or shop at the market. They have each other’s backs. “There is a lot of concern,” says Olga Domínguez, from the Casco Viejo neighbors’ association. “It’s a shame.”

I tell the bank I am pregnant and that puts the brakes on things Advice on advert for squatter flat

This feeling of vulnerability is driven by exceptions such as that of 31-year-old computer specialist Isidro Barqueros, who bought his apartment from Santander Bank. Obviously in this case the black market ‘realtor’ had got its facts wrong and did not realize it had been sold.

Barqueros began refurbishing the property. Last week, he dropped by to see how the work was going and was pleased with the progress. Only the floor was left. When he returned two days later, he found the lock had been broken. It took him a moment to realize he had ‘guests’ and then he went straight to the police precinct across the road. Several officers returned with him to his property and knocked on the door. A female voice from within shouted back. She had no intention of opening up, she said. She would stay inside with her two daughters, one of whom was a minor.

A neighbor informed Barqueros and the officers that the women had moved in 12 hours earlier. The officers threatened to break the door down, but fortunately it did not come to that. The woman and her daughters left and said sorry.

She told Barqueros and the officers that she had paid €400 to a man who had helped her force the door open. She was going to pay him €500 but when she saw there was no cooker, she demanded a discount. Barqueros tweeted about what happened and the response was overwhelming.

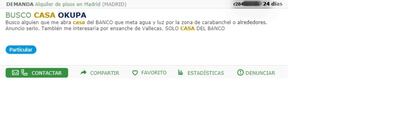

Many of those hoping to find a place to squat have fallen on hard times. Thirty-two-year-old Antonio Ruiz, for example, lost his job five months ago and, though his wife has a cleaning job, with two children it is difficult to make ends meet. Ruiz is looking for a place to squat in the Carabanchel area so that his daughters do not have to change schools. “I’m currently in a rented apartment,” he says. “But the contract is up. I am looking for a place that belongs to a bank to avoid squatting in someone’s house.”

There are dozens of ads like Ruiz’s, placed by people desperate for somewhere cheap to live. “I need an apartment urgently,” says one. “I have no work and have to move out of the place I am in now. I can’t afford to pay rent and I don’t know where to go with my children.” This particular ad, found in Milanuncios, offered €1,000 for an apartment owned by a bank.

A Squatters Manual

The Platform for Mortgage Victims (PAH) also help families to squat, but the process is one stipulated in a document called The Civil Disobedience Manual for the Repossession of Empty Homes Belonging to Financial Institutions. This manual prohibits the occupation of private property and it rules out paying fees. "In PAH, we try to make it a last resort because families [squatting] will then be living in fear. Even so, it is an option we consider because for some families it is all that is left to them," says Belén from PAH.

The manual explains how to go about squatting: first, you need to get all the information you can on the property in question. Next, you need a plan to move in without being noticed. It is advisable to get in through the door or through a window and with minimal damage. Once inside, block the lock to prevent the owners entering. This can be done with superglue or tooth picks.

To prevent the police entering, squatters should initially use chains and padlocks to keep them out. They then need to get a new lock fitted. That shows that they have been there for more than 48 hours, which turns it into their property – at least temporarily. If the police manage to come with a warrant, the squatters can be accused of theft. To avoid that situation, they should put up notices that they are squatters, not thieves.

The squatters can be accused of usurping the property if there is evidence of forced entry. But in this case, the judge needs to name the suspects. This is why the manual recommends carrying out the operation out of sight of witnesses or cameras that might subsequently identify them. The case is then heard by a local court and, if faced with a well-prepared defense, can take two years to be resolved.

English version by Heather Galloway.