In bed with Roberto Polo

Roberto Polo is not easily defined. The owner of a vast art collection, some of which is being shipped to Toledo and Cuenca, he was friends with artists, bankers and celebrities in 1980s New York. He also did jail time, had a close call with death, and was born again. This larger-than-life character has a motto: “Only mediocre men never have problems”

Known as Marranos, the Jews who converted to Catholicism in the 15th and 16th century would walk through Toledo with their eyes cast down for fear of being betrayed and exiled, or even executed. Roberto Polo also had a downcast period in 1988 when he was in preventive prison for alleged misappropriation of investors’ funds.

Those were dark times for Polo, who had graduated from Columbia University and made a name for himself as a painter, collector and investor. Something of a golden boy in New York, he counted Andy Warhol, Robert Motherwell and Grace Jones among his friends. “I would stare at the ground because it was all so horrible,” he says about his prison time, leaning back on a sofa inside his home in Brussels.

Polo has donated art to the New York Metropolitan Museum, the Victoria & Albert and the Louvre

It’s a far cry from the man he is today. At 67, he is brimming with optimism over his latest project: part of his vast art collection – 445 works out of a total of 7,000 – is being transferred to the Spanish cities of Toledo and Cuenca to be exhibited on a 15-year renewable loan, thanks to an agreement signed on July 25 between Polo and the head of the regional government of Castilla-La Mancha, Emiliano García-Page of the Socialist Party (PSOE).

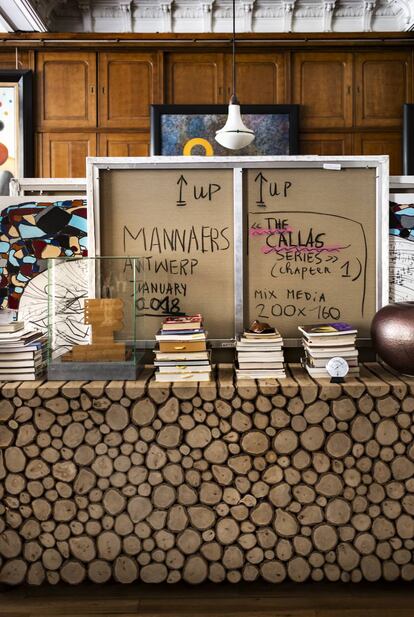

Hundreds of contemporary paintings and sculptures are due to be shipped from Polo’s house and several storage areas in Brussels; some of them will be taken to the 13th-century Santa Fe convent, which is attached to the Santa Cruz museum in the old quarter of Toledo, while others will find a temporary home inside Casa Zavala in Cuenca, where they will stay until the Regional Historical Archive building – once the headquarters of the Spanish Inquisition – is fully refurbished. Both venues will open their doors to the public in February. The museum project for the Santa Fe convent will be run by Juan Pablo Rodríguez Frade, who has carried out spectacular architectural conversions on the National Archeological Museum, the Alhambra Museum and the Museum of Abstract Art in Cuenca.

The treasures to be housed here include works from Eastern, Central and Northern Europe and from the US, many by artists all but absent from Spanish museums. Among them are stars of the modern art scene such as László Moholy-Nagy, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Oskar Schlemmer, Kurt Schwitters, Max Ernst, Man Ray, Franz Marc, El Lissitzky, Paul Joostens and Jacques-Henri Lartigue. But there are also 20th- and 21st-century US artists, photographers and sculptors such as Larry Poons, Ed Moses, Karen Gunderson and Melissa Kretschmer, as well as contemporary Belgians such as Jan Vanriet, Mil Ceulemans, Werner Mannaers and Carl De Keyzer. And, last but not least, eminent artists from the 19th century such as Eugène Delacroix, whose depiction of a fisherman’s wife on the beach will be the second Delacroix to be exhibited in Spain, while Honoré Daumier’s Three Lawyers in Conversation will be the first Daumier on Spanish soil.

“If things go well, I may end up donating my collection to Spain,” says Polo, a philanthropist who has also donated works to the Metropolitan Museum, the Victoria & Albert, the Louvre, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Nelson-Atkins Museum, the Château de Chantilly and the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels. His donation to the Louvre was the crown belonging to Napoleon III’s wife, Empress Eugénie, which he himself had picked up at an auction. “Spain is going to get important works of art by artists that have never been shown in this country or hardly at all,” says Polo.

Museum trustees include multimillionaires who call themselves collectors, but really they are just speculators

Polo was born in Cuba in 1951 into a family that was originally from the Spanish northwestern region of Galicia, his great-grandfather being the composer José María Castro, better known as Maestro Chané. The family’s fortune was built on the construction of storage tanks for oil refineries, bridges, railways and sugar mills, but they fled when Fidel Castro took power. Subsequently, Polo’s adventures took him to Lima, Miami, New York, Massachusetts, Washington, Paris and Brussels, where he has been living for over a decade.

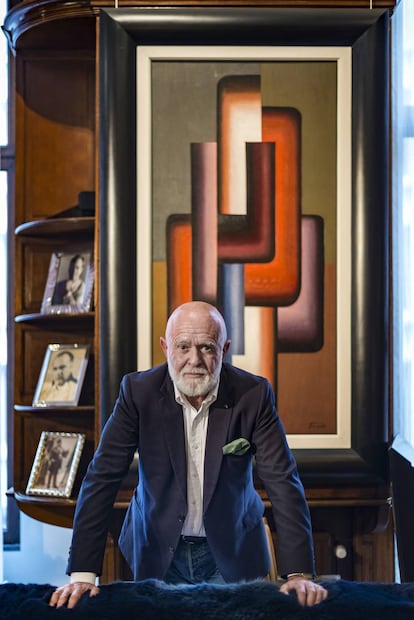

Soon to move to Toledo, we catch him at his home on Rue du Lombard, a stone’s throw from Brussels’ main square, the Grand-Place. It is a charming former hat shop with wooden walls and floors and ornate ceilings, an elegant three-story affair packed with artworks among which he and his husband Michel’s whippet, Otello, picks his way quietly.

There are piles of books that spill over into the master bedroom where Polo, who speaks perfect Spanish, English, French and Italian, prefers to read and work. And not only is he happy to have his bed photographed, he jumps into the frame. Polo is a real one-man-show. His obsession for aesthetics and his sense of flair must come at least in part from those years in New York when he rubbed shoulders with the most glamorous and avant-garde that society had to offer.

Today, seated on a sofa near the magnificent Toledo-bound Groteske III sculpture by Oskar Schlemmer, Roberto Polo takes us back to those days, and more specifically to its nights. “The atmosphere was one of limitless freedom,” he says. “I lost a lot of friends to AIDS, such as for instance the illustrator Antonio López, who was an incredibly talented guy, a genius. And I remember crazy nights in Mister Chow, the Chinese restaurant run by the Chows who were art collectors. At midnight, that place was a swimming pool of champagne, with Brazilian girls dancing on the tables, all great fun. One night, I was waiting to get into the bathroom. There were both girls and boys standing in line. After a while, I realized that the line wasn’t for the bathroom, but for sex with Antonio. He was a sex machine. He and I and Warhol used to go around with a Polaroid camera taking photos of all the people who caught our eye and documenting the night – Paloma Picasso baring her breasts, Karl Lagerfeld building up his muscles, Valentino…” Joan Fontaine, David Hockney, Paloma Picasso and Mexican movie star María Félix were also friends. From Félix he would buy a huge 41.37 carat Ashoka diamond for his former wife, the Dominican-born Rosa Polo.

But it is Andy Warhol with whom he appears to have been particularly fascinated. “Andy was very Zen. I never saw him on drugs, although everyone around him usually was. He had the strange ability to drive the people around him crazy. Perhaps it was the way he manipulated the weakest. They were his entourage, his groupies, but among them of course there were also very brilliant people. Probably the most brilliant of all was the guy who made Andy’s works of art, an Italian-American named Ronnie Cutrone who was pretty unknown. Warhol signed them, but clearly it was Ronnie who made them.”

I dropped down to 40 kilos. I thought I was going to die

An afternoon chatting with Roberto Polo, complete with lunch made by his Italian cook Robertino, provides enough material to fill several books. A bon vivant who is only too aware there is a both a bright and a dark side to life, his every utterance in some way helps understand what makes him tick. For example, at one point he reveals: “I got my first erection looking at a painting in a museum; it was a work by Bonnard in the Philips Collection in Washington. I was about 12 years old.”

Polo’s biography is like a financial graph with its peaks and troughs. He studied at the prestigious Corcoran School in Washington; he worked as a bookseller in Rizzoli; he painted and stopped painting; he organized fashion exhibitions such as Fashion as Fantasy in New York; he launched a company called the Private Asset Management Group that handled investments for important businessmen; he was accused of financial crimes by a number of them, including the Mexican entrepreneur and politician Emilio Martínez Manautou; he spent over four years in preventive prison; he put together collections of French paintings from the 18th and 19th centuries, then he built modern and contemporary art collections such as the one he is bringing to Spain; he became an expert in precious stones and began to collect jewels, ultimately creating one of the most important gem collections in the world.

When all is said and done, if there is one thing Polo knows a lot about, it is the art market. He once owned 51% of Sotheby’s together with his partners. “For the past 30 or 40 years, most gallery owners have been people who do not know about art,” he says. “They’ve created a new public, a new kind of customer who knows nothing just like them, and their message is that the only important thing is, ‘I like it’ or ‘I don’t like it’. And they’ve created a new kind of art that has to do with fast consumption, like advertising: that the colors in the painting must go well with the sofa and such like. And there are customers who ask for a picture with such and such measurements for their wall. But a real collector doesn’t buy a picture thinking about where they are going to put it in their home. They buy it from necessity, because they really want to own it.”

Polo goes on to illustrate his point. “It’s like when Peggy Guggenheim commissioned Jackson Pollock to paint her a mural. Pollock painted one that measured six meters. And one day while having afternoon tea with Marcel Duchamp, she said, ‘But where will I put it? My biggest wall measures just five meters!’ And Duchamp replied, ‘What are you? A collector or a decorator?’ And she said, ‘A collector.’ And Duchamp said, ‘Well if you really are a collector, put the six-meter mural on the five-meter wall because the main thing is that the mural must live with you!’

Polo is just as scathing about contemporary art museums. “The same thing happens more or less in contemporary art museums nowadays,” he says. “There’s a list of between 30 and 50 artists who are crucial if you’re in charge of the museum and if you don’t have these artists, it’s as though you haven’t succeeded. You’re not part of the club. On the other hand, big museum trustees include multimillionaires who call themselves collectors but they aren’t. Really, they are just speculators.”

During the late 1980s, when he was accused by clients of financial wrongdoing, Polo experienced arrest, prison and a suicide attempt. Then came the recovery and the personal renaissance. “Only mediocre people don’t have problems. Only they are able to maintain a straight line in life,” he says.

“I’m very proud of that period of my life. Prison is a microcosm of the world. There are as many guilty people inside as outside. In fact, there are many more outside. When that happened to me, I thought I was going to die. I was locked up for three-and-a-half months in solitary confinement, naked, without even a window, on the pretext that I was an important person who had to be protected from the other inmates, but it was a big lie. What they really wanted – and I was beaten in a bid to get it – was that I should reach a deal with the Mexican politician and his gang of criminals who, using companies in tax havens, had filed the criminal complaint against me. Their only goal was to rob me, and my ex-wife was in on it. I never signed the deal. I dropped down to 40 kilos. I thought I was going to die. I spent four-and-a-half years in preventive prison – not one day was spent as a convicted criminal – until a tax investigation by the US government showed that I was clean. What saves a man in that kind of situation is the absolute conviction that they are innocent. That, and having other projects. Anyone who doesn’t have a project will die.”

English version by Heather Galloway.