Secrets from an asylum in Madrid: rage, squalor and unanswered letters

Psychiatrists compile book of moving messages by mental institution patients from 1852 to 1952

The first patients to be admitted to the mental institution known as Casa de Santa Isabel in Leganés, south of Madrid, surely arrived on horse-drawn carts. Raimundo, a doctor from Guadalajara, was transferred there at the age of 47 along with 21 other workers. It was April 25, 1852.

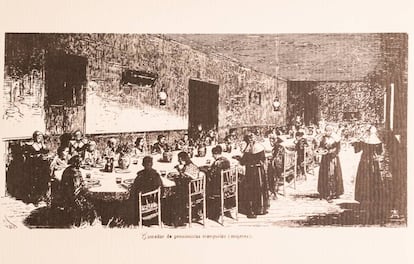

These employees arrived shortly after the first female patients had settled down inside their separate pavilion, complete with a special wing for “agitated women,” since “agitation and rage are traits more common to the female sex.”

The letters were considered a form of therapy and an aid to diagnosis

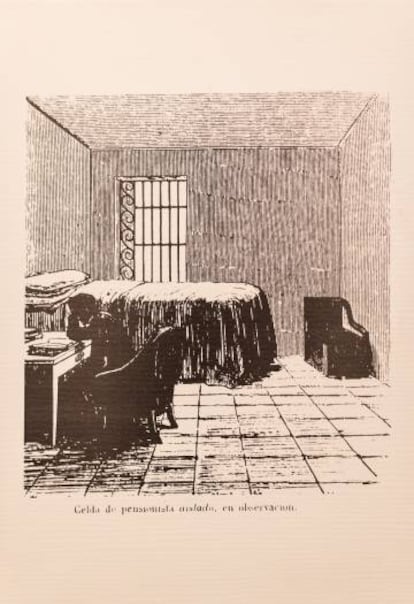

The institution, which had been inaugurated some months earlier, was in fact the refurbished palace of the Duchess of Medinaceli. By the time they had finished with it, conditions were, however, far from palatial. Besides the cold and hunger, many of those admitted were restrained with strait jackets and faced all kinds of tribulations.

Records of these daily horrors were filed away and have just recently been dusted off along with medical reports and desperate letters written by patients begging to be released. Sadly, these letters never got beyond the boundaries of the institution.

The letters, written upon encouragement by the doctors, were considered a form of therapy and an aid to diagnosis, but were never actually mailed. Now, they are reaching a far wider audience than their authors surely expected as part of a book titled Cartas desde el manicomio (or Letters from the Asylum), published by Catarata.

One of the patients was a brilliant lawyer whose name the book authors render as Anselmo (all real names have been changed). Once a professor of law at Havana University and a mayor, in 1846 he apparently began to show signs of exaggerated anxiety and agitation that were, according to his case history, “the result of an excessive amount of work and the immoderate intake of coffee.”

He was subsequently admitted to the Casa de Dementes de Santa Isabel, where he spent 11 years, allegedly putting up with the nuns who made fun of him. “I no longer attend Mass, or indeed go anywhere near it,” he wrote in a style that betrayed his higher education.

The letters compiled by Olga Villasante, Ruth Candela, Ana Conseglieri, Paloma Vázquez de la Torre, Raquel Tierno and Rafael Huertas were written between 1852 and 1952 against a backdrop of epidemics, charity laws, deprivation of all kinds, kings and queens, two republics, a civil war and a dictatorship. They also reflect a society that was rife with domestic violence, Catholic fervor and many forms of abuse.

Disturbing testimony

One of the most arresting letters is from Adela, described as an “infantile” woman whose womb, according to the gynecologist, was correspondingly undeveloped. This, however, did not prevent her from marrying at the age of 19 and having five children. After her second child, she apparently began screaming from pain in her ovaries, prompting her husband to administer morphine. He later withdrew the drug and accused her of squandering money and being unfaithful. This, she maintained, was the reason why she had been carted off to the asylum.

In her letters, she begs him to visit her with the children. “I promise not to speak at all about leaving. Write to me and tell me about our children. Who is looking after Rafaelín? Who is braiding my daughters’ hair? And Pepín’s arm? Is Antoñito studying? I have all of them and you in my heart […] Remove me from your life, but for Heaven’s sake let me be with my children.”

Once admitted, mental institution patients could expect to be there for life

When this letter was written, Rafaelín would have been just three months old and her mother’s “breasts were full of milk” which she was unable to express, resulting in “terrible colitis and horrible pain.” Desperate, she asks her husband: “Do you know where you have sent me? Do you have any idea what an asylum is?”

In the 19th century, there was often no escape from a mental institution and patients, once admitted, could expect to be there for life. The institution would be understaffed with no more than a couple of doctors and a few nuns carrying out their duties with scant resources and poor hygiene. The sanitary conditions at the Casa de Dementes de Santa Isabel was so bad, in fact, that the mayor of Leganés became concerned about infection spreading from the asylum, which smelled horribly and was home to hordes of rats – all this just a stone’s throw from a girls’ primary school.

Asylums were often used as dumping grounds for unwanted dependents, but it is hard to judge from the letters which of the patients would have fallen into this category. “Throughout history, there have been many baseless admissions. But it is difficult to judge from these letters who was really ill and who was simply the victim of some ill-intentioned relative as they suggest, since persecution complexes are common in paranoid illnesses,” says Olga Villasante, a psychiatrist at Severo Ochoa hospital in Leganés.

“Both the patients and the doctors complained about them [the nuns] and it is true that in all areas of care there is a potential for abuse, but they [the nuns] were always there, unlike the doctors, and they took care of everything.”

Readers are invited to draw their own conclusions. “They say we are demented, disturbed and it is a miracle, Don Manuel, that we don’t indeed lose our minds upon seeing what those who discredit us hold as their truth,” writes Raimundo in a letter to his doctor. “How they forget the best and most recommended principles; how a brother-in-law becomes an authority figure with power over the disposal of a person’s assets and fate.”

“The letters are so powerful that they deserve to be read as they are, in the original voices,” says Rafael Huertas, another one of the psychiatrists responsible for putting the book together.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.