A head trip round Guggenheim Bilbao with Henri Michaux

Museum pays tribute to the highly original artist, from his early years through his psychedelic period

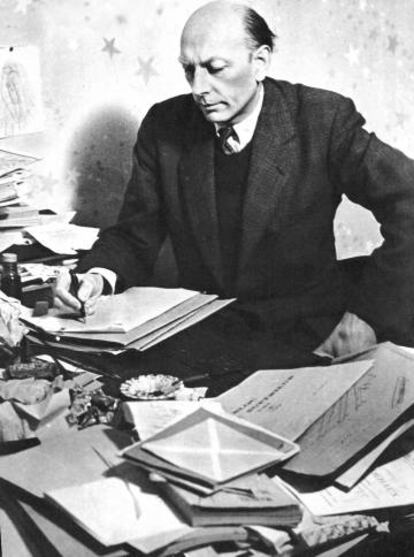

The Belgian-born, highly idiosyncratic poet, artist and traveler Henri Michaux was a late bloomer on many fronts. It wasn’t until he was 25 years old that he began to explore the world of color and canvas. Apparently, the German artist Paul Klee had convinced him that abstract painting could prove to be the right medium to express the inexpressible, which was Michaux’s personal holy grail.

Similarly, he was 55 when he began experimenting with hallucinogenic drugs such as hashish, LSD and mescaline. Yet it would be thanks to the inspiration drawn from this eye-popping cocktail that he would become the darling of the art world’s counter-culture.

Now, Bilbao’s Guggenheim Museum pays tribute to one of the most unique and influential artists of the 20th century in an exhibition that is showing until May.

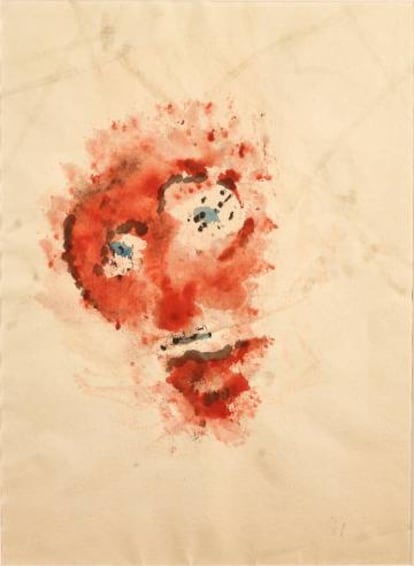

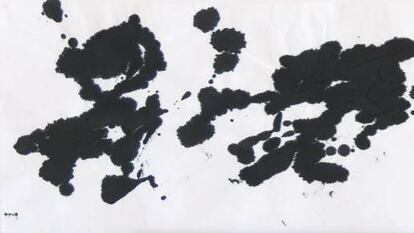

The ‘trip to the other side’ laid out by the museum is split into three sections. It begins with his exploration of figures and the human face, and moves to calligraphy and the invention of ideograms and alphabets, until finally the visitor is met with the psychedelic art created under the influence of psychedelic drugs towards the end of the 1950s. This last period turned Michaux, who described himself as “the sober water-drinking type,” into a point of reference for the psychedelic revolution which was cooking in university laboratories on both sides of the Atlantic and which would define the hippy era.

All those involved in the exhibition, including museum director Juan Ignacio Vidarte, refer to Michaux as “the painter’s painter and the poet’s poet”. And it has been made clear that his use of drugs had nothing to do with addiction or casual recreation. Rather, he took the drugs under the supervision of scientists and tried to conjure up images and words while under their influence, scribbling down what he saw in his mind as best he could.

Once he had emerged from the ‘trip’ he would convert these visions into drawings and detailed descriptions of the creative effects of the drug. His declared aim, however, was simply to “explore the mediocre human condition.” In the preface to Miserable Miracle (1956), one of three of his most intriguing works on his mescaline experiences, Mexican Nobel prize winner Octavio Paz wrote: “Perhaps Michaux has never tried to express anything. All his efforts have been directed at reaching that zone, by definition indescribable and incommunicable, in which all meanings disappear.”

The drawings and sketches from Michaux’s psychedelic period are notably more intense and agitated than his earlier work. One of his oldest drawings, La Paresse (1934), for example, contrasts quite dramatically with his better-known inks. Manuel Cirauqui, the show curator, has brought together around 220 pieces, some of which have never been shown to the public before, but most of which hail from the Michaux Archives in Paris. Also on hand is Michaux specialist Franck Leibovici, who works at the Paris archives.

Cirauqui has avoided putting the pictures in chronological order, aiming instead to highlight parallel interests and recurring themes across the decades. And he has thrown into the mix some of the artist’s personal belongings, such as tapes of rhythmic music that reflect a passion that was to dazzle the composer Pierre Boulez. There are also sculptures from New Guinea, Borneo, Central Africa and Australia that were brought home from his wanderings abroad.

Michaux was 55 when he began experimenting with hallucinogenic drugs

The exhibition opens with these exotic artifacts before moving into a gallery of portraits that seem to emerge haphazardly from the ink. “Whatever I do, faces always appear,” said Michaux, who defied labeling and created his own unique brand of avant-garde fantasy. An intensely private man, Rafael Conte would reveal in Michaux’s obituary in 1984 in EL PAÍS: “In the last 20 years of his life, he refused to be photographed or to allow journalists or people studying him access to even the smallest details of his private life.”

“He was not an artist who worked with a preconceived idea or aim,” says Cirauqui. Instead, he would pick up a piece of paper, throw a certain color on it and see what emerged, then work on that. In total, he would keep 10,000 drawings, perhaps because illness prevented him from destroying them.

In the abstract splashes of color exhibited in the Guggenheim, one can see almost anything, from a grimace to a dancing figure or a tangle of squiggles such as one might make when talking on the phone. And somehow, from this, a portrait of the artist himself emerges, a man who became a case study for literature and art in the 20th century. Or as US art critic Anatole Broyard once described him: the “poet laureate of our insomnia.”

The writer and the psychiatrist

The museum is keen to call attention to the relationship between Henri Michaux and the psychiatrist Julián Ajuriaguerra, born in 1911 in the Deusto district of Bilbao, who pursued his career in exile in Switzerland and France. A brother to Juan Ajuriaguerra, the famous president-in- exile of the Basque Nationalist Party(PNV), Julián helped the poet in Paris with his psychedelic experiments and wrote an unedited text in 1963 which is included in the exhibition catalogue, titled: ‘There is nothing. Contribution to a familiarity with toxic psychosis, Experiments and discoveries of the poet Henri Michaux’. In it, the psychiatrist details the effects of each psychoactive substance tried by the painter for “purely scientific” purposes. Comparing Michaux to other literary giants such as Thomas de Quincey and Charles Baudelaire, who experimented with hallucinatory drugs, Ajuriaguerra concludes, “Right now, no other writer has better explored the matter.”

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.