Rafael Yuste, neuroscientist: ‘We have to avoid a fracture in humanity between people who have cognitive augmentation and those who do not’

The researcher, who teaches at Columbia University, has been promoting the new National Center for Neurotechnology in his native Spain. The institute will manufacture devices capable of tapping the human mind and modifying it

Almost a year ago, an unusual scene took place in Spain’s legislature. A small group of lawmakers sat down to watch the latest film by German filmmaker Werner Herzog, Theater of Thought (2022). The documentary warns that neurotechnology — devices capable of reading, or even modifying, the activity of the human brain — are about to transform the world forever. The director’s hypnotic voice-over resonated inside the Congress of Deputies:

“In the future, will you be able to read my mind and see my next film before I even shoot it?” Herzog asks a researcher at one point in the film. The neuroscientist Rafael Yuste, who features in the documentary, was seated among the Spanish lawmakers, trying to raise awareness about the risks of penetrating the human mind. His answer to the filmmaker’s question is shocking: “Probably.”

Yuste — who was born in Madrid 61 years ago — heads the NeuroTechnology Center at Columbia University, in the heart of New York City. He tells EL PAÍS that, a decade ago, his life changed because of an experiment. “By studying the visual cortex of a mouse, we were able to not only decipher what it was seeing, but also manipulate its brain activity to make it believe that it was seeing things that it wasn’t seeing. It was as if we had put a hallucination into its brain. And the mouse began to behave as if it were really seeing this false image. We manipulated it like a puppet. I didn’t sleep that night,” he recalls, via video conference from a suburb of Madrid. “What we can do today in a mouse could be done tomorrow in a human. We’ve opened the door to some very serious ethical and social problems, as happened to the physicist Robert Oppenheimer with the atomic bomb,” he reflects.

The Spanish neuroscientist has been working in the shadows for five years to shape the forthcoming National Neurotechnology Center, which will be located in a building at the Autonomous University of Madrid. With a promised investment of over $200 million by 2037, it’s one of the largest initiatives in the history of Spanish science. Yuste — who defines himself as the “instigator” of the project — explains that he’s currently negotiating to join the center as scientific director.

Question. In an interview you gave three years ago, you said that “having a sensor on your head will be the rule in 10 years, just like everyone has a smartphone now.” There are seven years left. Do you still think that this will be the case?

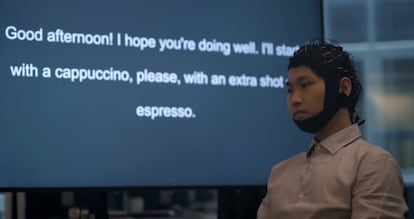

Answer. I don’t know if it will be mandatory, but things are moving super fast. More than a year ago, a team from the University of Technology in Sydney (Australia) and a neurotechnology company developed an electroencephalography cap, coupled with a generative artificial intelligence system. They managed to decipher the mental language of volunteers with an accuracy rate that was low on average — around 40% — but with great accuracy in some cases. There’s a video in which you can see how they decipher the words that a person is generating in their brain: “Good afternoon, I hope you’re doing well. I’ll have a cappuccino, please, with an extra shot of espresso.” In reality, we don’t know what a thought is, but we do know the language. [These systems can] decipher words that aren’t spoken. The potential is brutal.

Q. What are these researchers trying to achieve?

A. I suppose this Australian company wants to build a system so that you can, for example, type on a computer by just thinking, without using your fingers. I think we’re relatively close to that happening… and, when it does, it will be a revolution. Imagine that you’re wearing one of these helmets or a cap: you can generate language internally, have it decoded by the system, communicate with other people, give instructions, operate robotic equipment… a whole world is going to open up. We have to anticipate the future that’s coming our way, in which we’re going to use neurotechnology in everyday life, just as we use mobile phones right now. [This] neurotechnology will also increase our mental and cognitive abilities.

Q. How will it increase our abilities?

A. For example, two years ago, a team from Boston University used electromagnetic neurostimulators on [participants’] heads, in order to stimulate a part of their brain and increase memory by 30%. It was a control experiment, so that [these devices] could later be tested on patients with Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of dementia. Let’s imagine they start to get sold: “Do you want to have a better memory? I’ll sell you an electromagnetic stimulator that costs $1,000 and will boost your memory.” We’re going to have a situation in the world where, with neurotechnology, we can start to “touch up” brain activity. Not just decipher it, but change it. We’re talking about something very big, because brain activity is the sanctuary of the human mind. That’s where everything that we are comes from: our thoughts, our emotions, our beliefs, our personality, our memories. With neurotechnology, you can map mental activity and change it. It can have fantastic applications: understanding what happens inside [the brain], [developing] systems for typing based on thinking, all the medical uses... but there are also many risks, because we’re opening the lid of people’s minds with technology. We have to make sure that this is super-protected from the start.

Q. What will the National Center for Neurotechnology be like?

A. It will have more than 250 researchers and there will be three large departments dedicated to manufacturing neurotechnology: devices to measure human brain activity and modify it. One department will be made up of neurobiologists, with methods concerning genetics, molecular biology and cell biology. Another will be made up of neuroengineers, with electronic, magnetic and acoustic methods. The third department will be about artificial intelligence. And then, there’ll be three other small departments: one to coordinate clinical trials throughout Spain to apply neurotechnologies to patients, a small business incubator to generate economic value, and another focused on ethics and human rights. Honestly, there’s nothing similar in the world.

Q. Spain’s Ministry of Science has pledged $123 million, including $40 million from EU funds. The regional government of Madrid will contribute $80 million, while the Autonomous University of Madrid will pitch in with just over $2 million. Is that enough money?

A. It’s [a fantastic amount]. I’ve seen [the commitment] first-hand and it’s been a beautiful thing that needs to be told. With the tragedy of Covid, which devastated Spain, European funds flowed in to rebuild the technological, industrial and scientific fabric. A historic opportunity arose for Spanish science, and the two most bitterly opposed administrations you could imagine have come to an agreement. They’ve put science above their differences. I’ve met with both Isabel Díaz Ayuso [head of the Madrid regional government, of the conservative Popular Party] and Pedro Sánchez [prime minister of Spain, of the Socialist Party] several times and I have no complaints. They’ve put in everything they had to and more.

Q. A couple of months ago, you and two colleagues warned that companies like Meta — which owns WhatsApp, Instagram and Facebook — and Apple have already patented, or are developing, wearable neurotechnologies that will soon reach the market with a global reach never seen before. These companies, then, are already invading that sanctuary of the human mind.

A. Yes, there are already small things happening, although they’re in the preliminary stages. That’s why it’s so urgent to protect mental privacy, because right now, there are lots of neurotechnology companies around the world that are already accumulating users’ “brain data.” They are selling devices that help you sleep better, meditate, [play] video games, pilot drones with your thoughts, move a cursor on a computer screen…

I’m concerned that these companies are hoarding all this data. It can already begin to be deciphered — as has been done in Australia — because artificial intelligence is improving spectacularly. It’s only a matter of time.

Q. Are you afraid that, for example, if you buy a video game with a headband that reads your mind to move a cursor, that the reading will reveal that you suffer from anxiety and that this information will end up in the hands of an insurance company?

A. Yes, this can already happen in principle. Medical devices in the United States are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration… the problem is with those that are intended for mass consumption. [In April of 2024], our foundation published a study of consumer neurotechnology companies. Our legal team read the fine print of all the contracts that the user has to accept in order to turn on the device or download the software. It’s a disaster. If you say “I agree,” the 30 companies take ownership of all your neural data. And practically all the companies authorize themselves to sell that data to third parties, which could be an insurance company, or the North Korean Army. It’s the least secure situation you can imagine. Since there are no laws, the companies say: “Well, for now, I get to keep everything and I authorize myself to sell it.” This situation worries me greatly. This hole must be plugged immediately.

Q. You say that the five basic neuro-rights are: mental privacy, fair access to mental augmentation, preserving personal identity, protection from bias and maintaining free will.

A. That’s right. Of the five, the most urgent is mental privacy, because, as I’ve said, today you can buy an electroencephalography headset on Amazon to play online and all that data is monopolized by the company that sold it to you. This must be stopped immediately. However, regardless of urgency, the neuro-right that I would put in first place in terms of importance is fair access to mental augmentation. Sooner or later, we’ll have to deal with this problem. We’ll have the possibility of [cognitively] augmenting ourselves… and this will create a gap in society. There’ll be two types of human beings: some who are augmented and others who are not. We have to start thinking now about how to avoid a fracture in humanity.

Q. Technically, when could that happen?

A. I think it will happen little by little. Perhaps memory-enhancing devices could be the first taste. I don’t know exactly when that will happen, but I see it happening in a matter of a few years.

Q. You’re the chair of the Neurorights Foundation, which is dedicated to raising awareness about the ethical implications of neurotechnology.

A. We’ve already managed to have brain activity protected by law in four places in the world. First, it was Chile: three years ago, it became the first country in the world to protect citizens’ brain activity. Then, in 2023, the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul did the same. And, in 2024, we managed to get two states in the U.S., Colorado and California, to pass laws protecting brain data. There are also bills being discussed in Uruguay, Ecuador, Mexico and Brazil at the federal level.

Q. And in Spain?

A. Nothing has been done in Spain yet, but there have already been two meetings. The first was in February, in the Congress of Deputies. There was a very welcoming attitude from all political parties. And, a couple of weeks ago, the Senate invited me to speak to the Science Committee. If all goes well, we’ll start working with legislators in 2025 to see if Spain also joins this movement and leads it at a European level. Spain would be the first country in Europe to have specific legislation to protect brain activity. The best solution would be to establish regulations at a global level, with a United Nations agreement and a specialized agency, such as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)… but that’s a very complicated and long-term objective.

Q. You’re one of the 12 members of the Spanish Research Ethics Committee. This body has analyzed the case of the rector of the University of Salamanca, Juan Manuel Corchado. He and his colleagues have had 75 studies withdrawn for fraudulent practices, but he has said that he’s not going to resign. The local newspaper La Gaceta de Salamanca has published an article claiming that it’s actually the ethics committee that has no ethics...

A. I can assure you that all the deliberations we’ve had have been scrupulous from the point of view of ethics and respect for the rights of the rector of the University of Salamanca.

Q. The ethics committee has been criticized by those close to the rector for being, supposedly, politicized in favor of the governing Socialist Party. However, you were appointed as a member of the committee by the regional government of Madrid, led by Isabel Díaz Ayuso, of the conservative Popular Party.

A. That’s right, I’m representing the Community of Madrid on the Ethics Committee. We actually represent the citizens. we have no political affiliation. I can assure you that there’s no lack of ethics in the committee, that really would be the last straw…

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.