Prehistoric bloodsuckers

Scientists discover evidence of ticks on a dinosaur feather preserved in amber 99 million years ago

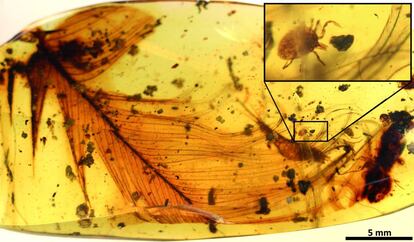

To stumble upon something as fragile as a dinosaur’s feather from almost 100 million years ago is unusual. Even rarer is the discovery of a fossilized tick. But to find a tick on a feather trapped in fossilized tree resin dating back 99 million years has proved nothing short of a miracle for a group of researchers working in the field.

“It’s easy for dinosaurs with big hard bones to fossilize,” says paleontologist Enrique Peñalver from the Geological and Mining Institute of Spain (IGME), who is heading the research. “But ticks are not very hard. All the ones that have been found are in amber. Where there’s no amber, there’s no fossil record of ticks.”

These are the oldest ticks ever found, apart from the example discovered in Spanish amber

The feather in question was found in the north of Myanmar and donated to the American Natural History Museum by a private collector. It was there that curator and co-author of the research, Paul Nascimbene, discovered what he believed to be a tick. Nascimbene contacted Peñalver’s team and also Xavier Delclòs, a professor at Barcelona University and a world expert on amber-preserved fossils.

The research, published in the journal Nature Communications, judges the Burmese amber to come from the middle of the Cretaceous period, around 99 million years ago. Leading on from the Jurassic Period, the Cretaceous Period ended around 65 million years ago with mass extinction, probably caused by a meteorite or asteroid colliding with the planet. This, then, is the oldest direct evidence of ticks feasting on dinosaurs. Identified as a hard tick, the specimen belongs to the Cornupalpatum burmanicum species. Apart from one yet-to-be-classified example preserved in Spanish amber, this is the oldest tick yet discovered.

However, according to Peñalver, no one would know this was the case. “If you could take it out of the amber and bring it back to life and gave it to tick specialists, they would never suspect that this was an animal from almost 100 million years ago,” he explains. Although this exact species died out a long time ago, its lineage survives in one of the three groups of tick around today.

The researchers have also identified and classified another four ticks from a previously unknown species, which they have christened Deinocroton draculi. All four, whose lineage has not survived to the present day, were found in Burmese amber while two – a male and a female – have been fossilized in the same piece of amber. The researchers also found clues suggesting that these four fed off feathered dinosaurs, though there is no evidence as decisive as the tick on the feather.

One such clue is in the marks on the abdomen of beetle larva, which can be found today in birds nests. But the possibility that the animals they fed from were birds as we know them has been dismissed as they didn’t figure until 25 million years later. “We know that it was a feathered dinosaur but we don’t know if it flew or not,” says Ricardo Pérez de la Fuente, from the Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

The amber, which comes from the vegetable resin of coniferous tress and several other plants, is the preferred time machine for paleontologists. As Pérez de la Fuente explains, “It doesn’t simply capture organisms almost instantaneously, it preserves the interaction between them forever.” Such is the case not only of the tick on the feather, but also of the insects caught in the Spanish amber with recently collected pollen still evident on their legs. This also applies to one of the gang of four, which died well fed. It must have fallen into the resin just after sucking the blood from its host, as its abdomen was 8.5 times bigger than that of its companions.

Unfortunately we have not yet reached the point where we can open the amber and extract the DNA of the dinosaur on which the tick was feeding, as was done in the 1993 movie, Jurassic Park.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.