Former ministers of Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez hid €2 billion in Andorra

Leading politicians suspected of taking commissions of up to 15% for awarding state oil firm contracts

Leading political figures, businessmen and front men took commissions of up to 15% for awarding state petroleum firm contracts

At least ten people including former vice-ministers, businessmen, their relatives and front men acting for politicians are suspected of earning more than €2 billion in illegal commissions for facilitating contracts with Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA during the rule of deceased Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez (1993–2013), according to reports compiled by police in Andorra.

A court in the principality of Andorra – a microstate situated between France and Spain – is now investigating suspected money laundering related to those activities.

The money received for the alleged bribes between 2007 and 2012 was paid into the bank Banca Privada d’Andorra (BPA), some 7,400 kilometers from the Venezuelan capital of Caracas. It was concealed in a web of 37 accounts to under name of Panamanian shell companies. Investigators believe the money was then moved to other tax havens, including Switzerland and Belize.

EL PAÍS has had access to the accounts of the alleged kingpins behind the scheme and to confidential information about the companies that were used in the operations. The network was formed by the former Venezuelan vice-ministers of energy Nervis Villalobos and Javier Alvarado, by a cousin of a former PDVSA president, and by executives at the energy giant. The group was rounded out by an insurance magnate and several front men.

Participants in the scheme informed the BPA’s compliance department – the office charged with ensuring that funds deposited in the institution do not have criminal origins – that the money stemmed from fees for advisory work carried out for PDVSA. However, investigators believe this work was never carried out. In other cases, reports costing millions of dollars were only a page and a half in length.

The judge overseeing the case believes the commissions involved were in the realm of 10–15%, chiefly from Chinese firms, and that these were received for contracts for oil extraction managed by PDVSA and its subsidiaries.

Evidence connects the network’s dealings with a deal between Venezuela and China under which the South American country received a loan of $20 billion from Beijing in exchange for oil. A PDVSA spokesperson has refused to comment, saying that it was a matter for prosecutors.

Money laundering network

Despite its misgivings, the BPA agreed to open the accounts even though the bank’s own internal control unit had warned that some of those accounts belonged to so-called politically exposed persons (PEPs) – people who have held a public position and must undergo special checks to avoid money laundering.

Authorities in Andorra, which had bank secrecy laws until last year, took control of the BPA in 2015 in an attempt to clean up its books, a move that came in the wake of US accusations that the financial institution was being used by criminal gangs for money laundering purposes – something that BPA owners deny.

The Andorra judge overseeing the investigation, Canòlic Mingorance, has targeted Nervis Villalobos, vice-minister for energy under Chávez from 2004 to 2006. The former minister was arrested in Madrid at the request of the United States over his possible involvement in another money laundering scheme. Washington is seeking his extradition. Villalobos is also being investigated by Spain’s High Court, the Audiencia Nacional, over possible bribes from Spanish engineering firm Duro Felguera.

Bad management sunk PDVSA

Venezuela and its governments largely depend on the performance and stability of the state oil company. The situation of Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), founded in 1975 during Carlos Andrés Pérez’s first term in office, has for years reflected the dire institutional and economic crisis that is gripping the country. But the last few months have seen an acceleration of the downfall of the only company that guaranteed the Bolivarian regime a presence in the international markets. In mid-November, the ratings agencies Fitch and Moody’s downgraded PDVSA amid speculation of imminent default. It also emerged that October registered a drop in oil production unseen in the last 30 years, according to OPEC. Analysts blame this drop on three factors: exchange imbalances, disinvestment and bad management at PDVSA.

Additionally, in August President Nicolás Maduro began firing and arresting company officials who had been trusted aides to his predecessor Chávez. The operation ended two weeks ago with the appointment of a military official, National Guard Major General Manuel Quevedo, to head the oil compay. Maduro also removed officials at PDVSA’s US subsidiary, Citgo. But the company’s collapse goes beyond Maduro’s attempt at hoarding power and his fear of betrayal. It has a lot to do with bad resource management, a culture of cronyism, and corruption.

Villalobos’s lawyers have declined to comment on the above cases, but evidence shows that the former vice-minister opened 12 accounts at the BPA and set up 11 shell companies. Some €124.2 million were deposited into those accounts, according to Andorra’s police.

For his part, Javier Alvarado, former vice-minister of energy and petroleum and former director of the Venezuelan national electricity corporation (Corpoelec) from 2007 to 2010, allegedly managed five accounts and four shell companies with total deposits of €46.5 million. One of those accounts was opened in 2008 when Alvarado was still with the Chávez government.

Meanwhile, Diego José Salazar, cousin of former energy minister Rafael Ramírez and a representative until just two weeks ago of the government of Nicolás Maduro at the United Nations, is suspected of setting up seven accounts and six shell companies. Some €21.2 million moved through those accounts. Salazar was arrested last week for his alleged involvement in the Andorra corruption scheme. This paper was unable to reach the lawyers of Alvarado and Salazar.

Closing in on Chávez’s strongman

Venezuelan prosecutors said on Tuesday that Ramírez, Chávez’s strong man, was being investigated for alleged petroleum dealings with his cousin. Ramírez does not hold accounts in the BPA and is not being investigated in Andorra.

Venezuelan authorities are also taking a close look at the hidden accounts of Venezuelan insurance magnate Omar Farias. Deposits in those accounts totaled €586 million, according to police reports.

Rodney Cabeza, vice president of Farias’s firm, Seguros Constitución, said that the money represents “totally legal reinsurance operations” and that the company only managed the PDVSA policy in 2006. Cabeza also stated that Farias had no professional relationship with the former vice-ministers Villalobos and Alvarado, while admitting that 50% of the insurance company’s books comprised government clients.

An analysis of the dozens of accounts at BPA show that most of the money was taken out of Andorra before funds were blocked by judicial investigators in July 2015.

Andorran police also highlight the existence of a cast of secondary figures who allegedly moved large sums of money in the principality. Among these is the business manager of Diego Salazar, Mariano Rodríguez Cabello, who opened 11 accounts and operated 10 shell companies with deposits of €626 million.

Investigators have also named José Luis Zabala, a representative of Salazar and Farias, who received €27 million, as well as former PDVSA in-house lawyer Luis Carlos de León Pérez, who was arrested in Madrid in October in connection with another corruption case.

Mirroring the massive Odebrecht case in Brazil, where the Brazilian construction giant bribed presidents, high-ranking officials and politicians in 12 Latin American countries over the course of five years, BPA used its subsidiary BPA Serveis to create a network of letterbox companies based in Panama to hide the money trail.

The alert over the alleged corruption was raised by French authorities after a suspect transfer of €89,000 was flagged. The beneficiary was an employee at a French hotel with the money described as “a gift for services rendered.” Investigators then came across the signature of Diego Salazar, cousin of the former Venezuelan ambassador to the United Nations Rafael Ramírez.

Then, in 2012, Salazar attempted to transfer €40 million from Switzerland to France, purportedly to purchase a property. The judge in Andorra blocked the operation. The BPA was involved in all of these cases.

The Venezuelan government reacted to the Andorra investigation with arrests last week – a move that comes two years after the investigation began. Prosecutors in Venezuela say some €4.2 billion was pilfered from the state energy firm.

The Chavistas who left Venezuala for security reasons

High-risk clients

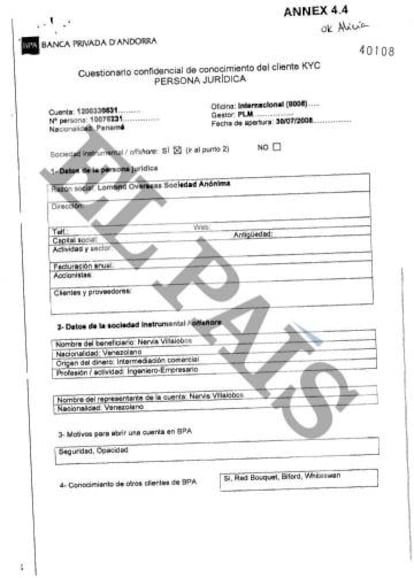

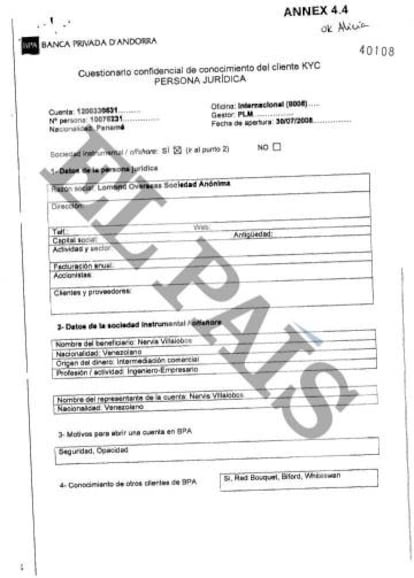

When former Venezuelan energy vice-minister Nervis Villalobos knocked on the door of Banca Privada d’Andorra (BPA), in June 2007, he was asked to fill a routine know-your-customer form, used to determine the origin of the funds. His answer to the third question, regarding his reasons for opening the account, was: “I want to keep my savings outside Venezuela, in a jurisdiction that offers legal security, stability and confidentiality.”

Villalobos became a BPA client one year after leaving the Venezuela executive, and until 2012 he had 12 deposits at the bank: one to his name and the rest concealed behind shell companies set up in the tax havens of Panama and Belize, according to documents that EL PAÍS has had access to.

Villalobos introduced himself as a successful engineer and said he wanted to deposit the fees for his “intermediary” services at the companies that he worked for, including the Spanish engineering firm Duro Felguera – which has declined to comment on the case.

In a document, the bank noted that Villalobos had deposits in Switzerland, Uruguay, the United States and Panama, and that his personal wealth was €70 million. An internal questionnaire shows that he listed BPA’s “opacity” as one of the reasons for opening an account there.

A report shows that Villalobos was investigated in 2006 for illicit enrichment together with the ex-president of the Foreign Trade Bank. The case did not reach the courts. There were possibly deviations (influence peddling) by some of his aides, according to a document drafted in August 2008 by the International Center of Economic Penal Studies (ICEPS).

Despite the alarms at BPA, which described Villalobos as a “high-risk client” and recommended “watching his transactions,” he had no trouble opening his accounts.

The BPA was also warned about the risk of taking on as a new client Javier Alvarado, former vice-minister of energy and petroleum and former director between 2007 and 2010 of the electricity company Corporación Eléctrica Nacional (Corpoelec).

Alvarado, who had accounts in the US and Switzerland, was planning to bring all his assets together at BPA. He introduced himself as an engineer specializing in advising the electricity sector. He said he was interested in BPA because of its “confidentiality and security.” And he announced that one of his accounts alone would be receiving $30 million a year.

“He is opening an account to deposit his funds outside Venezuela,” warned the BPA, which accepted the deposits despite considering him a high-risk client.

Diego Salazar, cousin of former energy minister, PDVSA president and UN ambassador Rafael Ramírez, did not have any trouble opening 11 accounts at BPA, either, despite being considered a Politically Exposed Person (PEP).

The BPA’s compliance department, which works to prevent money laundering, noted that Salazar held €70 million in his Andorra accounts: “He owns over 10 companies in Venezuela and significant real estate assets in Caracas, chiefly office buildings that he rents out to companies.”

Salazar opened his account in June 2007 together with his wife Rosycela Díaz Gil. Just like his colleagues, he also cited “opacity” as one of the reasons for opening an account at BPA.

English version by George Mills.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.