The Guernica treasure that turned up at Madrid’s flea market

Collector finds scrapbook capturing horror of bombing through eyes of repentant fascist photographer

One Sunday morning at a stall in the crowded Rastro flea market in Madrid, collector and journalist Javier Monjas asked the stallholder, “Excuse me. How much do you want for this?”

“Let’s see,” replied the seller, eyeing the yellowing scrapbook that Monjas held in his hands. “Give me €3 and we’re quits.”

The scrapbook was put together by Antonio Calvache, a flamboyant and successful photographer during the 1920s and 1930s

The scrapbook might have smelled of mold, but Monjas was interested in the war photographs that had been taped to the pages and the accompanying scribbles that were at once full of romance and outrage. He was not yet aware of the book’s true value, handing over the €3 out of curiosity more than anything else.

“Only when I got home and started to leaf through the book, did I realize the value of what I was holding,” recalls Monjas as he touches the scrapbook – a collection of Guernica originals as it says on the front. Besides being a photographic testament to the bombing of the town, it is also the epitaph of a tortured soul, a man filled with regret.

The scrapbook was put together by Cordoba native Antonio Calvache, a flamboyant and successful photographer during the 1920s and 1930s who was also a film director, actor, bullfighter, poet and friend of the stars. He created portraits of popular actresses of the day such as Conchita Piquer and Margarita Xirgu, royals such as King Alfonso XIII and Queen Victoria Eugenia, and intellectuals such as the writer Benito Pérez Galdós and the writer and philosopher Miguel de Unamuno.

And in 1934, he photographed José Antonio Primo de Rivera, the leader of Spain’s fascist Falange party, in his Madrid studio on San Jerónimo Street.

Enlisting with the Nationalist faction during the Civil War (1936-1939), Calvache was appointed head of the Falange’s Photography and Cinema section within its Propaganda Service. But he had no intention of spending his life stuck inside an office. He considered himself a man of action and his passion for photography and film, combined with his rash courage and a blind faith in Imperial Spain, took him to the frontline in northern Spain, and, more specifically, to the Basque town of Guernica.

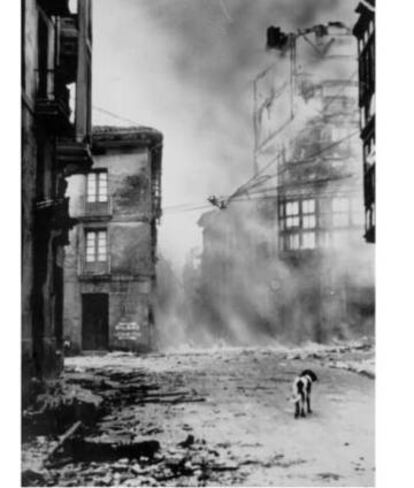

According to the scrapbook, he entered Guernica with the Navarre Brigades two days after the Nazi German Lufftwaffe’s Condor Legion bombed the town at the behest of Francisco Franco’s Nationalist government on April 26, 1937. That bombardment turned the town into a symbol of allied aggression with between 200 and 1,650 locals killed, depending on the source.

Antonio Calvache’s presence in towns such as Eibar, Bergara, Elgueta, Elorrio, Mondragón and Guernica during the spring of 1937 has been documented in Francoist propaganda films such as Marcha Triunfal (Triumphant march) and Frente de Vizcaya (Biscay Front). In fact, two days prior to the bombing of Guernica, Calvache had signed a contract in San Sebastián with a businessman called Duro to make two documentaries about the war in the north. He had already made one about the Teruel Front called El derrumbamiento del Ejército Rojo (The downfall of the Red Army).

Red, black, blue, white, have now become the same thing: pain

Antonio Calvache

There were rumors of a Guernica scrapbook, but its existence remained little more than a myth until Javier Monjas came across it in the Madrid Rastro. Signed by N. A. Villaespesa – the author insists that this is one of the family’s surnames, not a pseudonym – it is thought to have been put together at the end of the 1970s and it records the bitterness and shock that Calvache felt as he witnessed the fallout of what he termed “a nauseating crime.”

There is undeniable disillusionment at having belonged to a faction capable of such a massacre: “The total silence contradicts me. The arms in the air reach up in a painful spiral and the light seems to offer hope, a whiteness that the smoke blackens from below. Guernica? My heart stops. I am emerging from… NOTHING? … Nothing, nothing. GOD!… THEY HAVE TURNED GUERNICA INTO… NOTHING! […] LAND THRESHED BY BLADES WEIGHING 100, 500, 1,000 KILOS.”

Though he was a reactionary character, a certain lack of prejudice meant that he had photographed many important Republicans before the war, such as the Second Republic’s second Prime Minister Manuel Azaña and Colonel Emilio Buenoa, who was responsible for the Republican’s defense of the Vallecas part of the capital.

And then there was the incriminating episode on November 28, 1939, when the body of José Antonio Primo de Rivera arrived in Madrid’s Gran Vía avenue after being carried for 10 days by Falangist volunteers from Alicante. The procession passed the photography studio of a man called Alfonso who had been a Republican sympathizer, a friend of Azaña and a soldier on the Teruel Front.

Knowing the risk he was taking, Alfonso emerged from his studio to photograph the event. As he began to take the first shot, he was recognized by a group of Falangists who started to shout, “You! You Red bastard!” At that point, Calvache turned up with his camera and berated the bullies, who fell back. He then turned to Alfonso and said, “For crying out loud, Alfonso, what are you doing here?” To which the grateful Alfonso replied, “Nothing. Taking photos.” Calvache turned on the Falangists again and told them: “No one touches this man!” And he walked Alfonso home.

Unfortunately, such incidents carried a price, and Calvache used the scrapbook to talk about his own fall from grace. “Salamanca,” he writes, “was the kind of paradise where you had to pay for the fruit. Our last 1,000 pesetas were taken by the customs officials to check if they were red or white… and Franco didn’t even invite us to sit down.”

As Monjas points out: “And this is what happened to someone who headed the Falange propaganda machine! Instead of being a war hero, he ends up as vermin in the regime’s eyes and goes off to live in Tangier for some unknown reason. He is clearly very bitter about Franco.”

There is undeniable disillusionment at having belonged to a faction capable of such a massacre

Calvache’s fortunes were never to improve. At the end of his life, he would sell photos in the Rastro, at the entrance to the Prado and in Madrid bars, just to get enough to eat. He and his beloved wife, Aurelia Wandosell, would end up living like tramps surrounded by bags of rubbish inside their vast apartment at 49 Atocha Street.

He never renounced his Falangist ideals, but his disillusionment with Franco was such that he spoke about Guernica in some of the last paragraphs of the book in these terms: “Red, black, blue, white, have now become the same thing: pain.” It is the voice of a disillusioned fascist.

Juan Miguel Sánchez Vigil, a lecturer at Complutense University in Madrid, got his hands on 2,500 of Calvache’s photos after his death in 1984. He was tipped off and acted swiftly before the Madrid sanitation department moved in to empty their home and throw out the photos together with all the accumulated trash into a nearby dumpster.

After some research, Sánchez Vigil was able to stage an exhibition of Calvache’s work at Madrid’s Conde Duque Cultural Center in 1994. He then went on to compile a book called A través del espejo (Through the looking glass) using 137 humorous and tragic photos taken at different moments of Calvache’s career. A large part of his collection was then handed over to the National Library where, as Sánchez Vigil says, it really belongs.

Rumors of a Guernica scrapbook remained just that until Monjas stumbled upon it at Madrid’s Rastro market

“Both had lost their minds,” says Sánchez Vigil of Antonio Calvache and his wife Aurelia Wandosell’s final years. “I met the doormen at 49 Atocha street, the building where they lived. They told me that one day an order came from the Royal Family that the couple should never want for anything. The king and queen had invited Antonio Calvache to the palace to photograph them on a number of occasions in the past. So they organized for food to be brought to them every day. The Red Cross would come with food and leave it with the doormen to take up to the apartment. Until one day, they knocked and knocked and no one answered. The fire department went in to find Calvache dead and his wife on the ground surrounded by bags of trash, clothes and photos.”

Aurelia Wandosell died in 1998 in a nursing home. They had no children. Their only living relative was a niece of a cousin of hers who had lost touch with them some years earlier.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.