Spanish authorities make new bid to compensate “thalidomide babies”

Health Ministry in talks with victims’ association to draft census ahead of possible financial aid

The Spanish Health Ministry and the Spanish Association of Thalidomide Victims (Avite) are in talks to draw up a census of people who were affected by a drug that was manufactured by a German company in the 1950s. Thousands of babies born to women given thalidomide to combat morning sickness were born without arms and legs in the 1950s and 60s throughout the world.

The idea, said a ministry spokeswoman, is to learn exactly how many victims there are in Spain, and then, at a later date, to seek a way to award them compensation.

The victims have been battling in the courts for years. But in September 2015, the Spanish Supreme Court ruled that these victims are not owed compensation because the statute of limitations on the case has run out.

Authorities in Franco-era Spain did not want an investigation into thalidomide

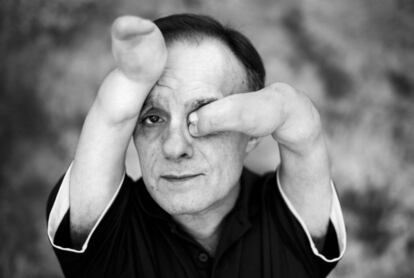

Avite and ministry representatives have met once, and a second meeting is scheduled for May 17. José Riquelme, the president of Avite, said that this initiative is the result of a non-binding motion that Congress passed in November of last year. The motion, which seeks greater protection for thalidomide victims, was introduced by the centrist party Ciudadanos, which has agreed to back the minority government of the Popular Party (PP) in exchange for support on issues such as this one.

The first step in this new cooperation is to determine exactly how many Spaniards were affected by the drug. Officially, thalidomide was only on the market between 1957 and 1961, but victims say that the product recall was not complete.

Back in 2010, the Spanish government made an attempt to recognize the victims, but only 24 people were included in the official list. In 2012, 186 victims filed a class action suit to demand €204 million in damages. Although the original ruling was favorable to them, it limited compensation to the victims on the government list. Furthermore, the German drugmaker Grünenthal appealed the decision, and an appeals court upheld the claim, leaving victims without compensation. The Supreme Court later ratified this position.

The difficulty is, it is nearly impossible to find physical evidence such as doctor’s prescriptions or medication packages from 60 years ago. But victims note – as so do experts such as Claus Knapp, the Spanish physician who discovered the link between thalidomide and the birth defects – that patients can easily be recognized because these deformities are very characteristic, and include missing bones in the extremities.

Avite says it has around 300 members, but that there may be more who have not signed up (and even some paying members who are not truly thalidomide victims, admits Riquelme). He offers a ballpark estimate of around 600 across Spain.

Victims say they should be eligible for a special pension like the ones enjoyed by victims elsewhere in Europe

After a reliable census is drawn up, the next step would be to provide financial aid to the victims. But Riquelme does not support a lump sum payment like the one that the government awarded to a handful of people in 2010. Instead, he says they should be eligible for a special pension, “like the ones enjoyed by victims elsewhere in Europe.”

Many of those European pensions have in fact been funded by Grünenthal. The Spanish case is different because at the time of the births, Spain was under Francoist rule and the regime did not want an investigation into what had gone wrong, much less to find any culprits, as that would have involved the authorities. By the time the victims were able to seek redress, 40 years had elapsed, making everything more difficult.

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.