Fugitive in infamous 1977 Madrid far-right massacre is now a free man

Last arrest warrant for Lerdo de Tejada, who fled Spain before trial for murder of several labor lawyers, has expired

Fernando Lerdo de Tejada Martínez, a fugitive from justice since 1979 – when he fled Spain to avoid standing trial over the killing of labor lawyers in Atocha (Madrid) – is a free man. The last arrest warrant issued by the Audiencia Nacional, Spain’s High Court, expired in 2015, according to police sources consulted by EL PAÍS.

The member of the now defunct far-right party Fuerza Nueva (New Force) can return to Spain without fear of going to prison for his role in the assassination of four lawyers and a worker at a Madrid law firm with ties to the labor union Comisiones Obreras (CCOO) and to the Spanish Communist Party.

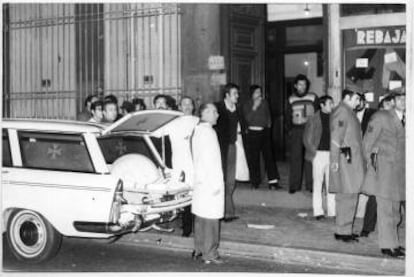

Gun in hand, Lerdo de Tejada was tasked with watching the front door while the attack took place within, on January 24, 1977. Five people were killed, while four others narrowly survived the point-blank shootings.

He vanished into thin air. I don’t know anything about what happened to him Brother of Fernando Lerdo de Tejada

The far-right murders were a critical moment for Spain’s fragile new democracy, given they took place just over a year after the death of long-time dictator Francisco Franco.

In its wake, the government of Prime Minister Adolfo Suárez, along with much of the population, feared that the country’s nascent transition from dictatorship to democracy had been wrecked. Instead, there were massive and peaceful street protests against the killings, and just as importantly, the authorities’ response was measured – all of which helped consolidate Spain’s new political system.

After the attack, four extremists were convicted to a collective prison term of 464 years. But unlike the others, Lerdo de Tejada, while prosecuted, never stood trial. He fled in 1979, during Easter leave granted by the Ciudad Real penitentiary, where he was in pre-trial custody.

Nobody knows whether the most famous fugitive of Spain’s transition to democracy is still alive. If so, he would be 63. Police records do not show him ever returning to Spain. Nor is there any evidence that he ever renewed his national ID card or passport, either inside or outside the country. And his police record shows no home address.

“The fact that there is no address or issue date for his ID card is due to a potential error when the data was transferred to the new system,” says a high-ranking police official, who ruled out a deliberate attempt by unknown persons to hide Lerdo de Tejada’s tracks.

But the far-right fugitive could have returned to Spain using a false identity.

“We never did find out where he went,” confesses the man who was head of Spanish espionage during the transition years, Lieutenant General Andrés Casinello. A police source familiar with counter-terrorism added that it is particularly difficult to investigate fugitives because judges balk at the idea of allowing wiretaps of their relatives’ phone conversations.

“He vanished into thin air. I don’t know anything about what happened to him. But if he is still alive, he will be protecting himself. We are as surprised as anyone else about his situation, and I don’t think it’s going to change,” claims one of his brothers, speaking on condition of anonymity.

But this version of events clashes with a source who is very close to the family clan: Martina, who worked for two decades as a housekeeper at the “White House,” to use the term popularly employed to describe the three-house estate that the Lerdo de Tejada family owns in El Toboso in Spain’s Toledo province.

“Fernando Lerdo de Tejada’s mother told me five years ago that her son was fine, that he had put on some weight and that he never married. He lives abroad, but I don’t know where,” says Martina, who has since retired.

During the Transition years, the Lerdo de Tejada matriarch, now in her nineties, collaborated with the founder of Fuerza Nueva, the since-deceased notary Blas Piñar. In January 1977, the far-right leader acted as a legal witness at the wedding of one of the clan’s 10 siblings, held at the family estate. Guests included military officials and three police inspectors. In this village of 2,200 residents, people still remember Blas Piñar’s constant presence at this wealthy family’s home during the final years of the regime of Franco, who died in 1975.

His mother told me five years ago her son was fine, that he had put on some weight and he never married Martina, former Lerdo de Tejada family housekeeper

Theories regarding the whereabouts of the Atocha fugitive immediately pointed to Latin America, where Spain’s extreme right extended its tentacles in the 1980s under orders from Blas Piñar and with help from accommodating dictators.

Juan León Cordón, who from 1983 to 1989 headed the Paraguay division of Frente Nacional (National Front) – a group born out of Fuerza Nueva’s ashes – admits that he has “heard talk” about Lerdo de Tejada’s presence in that South American republic.

“I was told that he was around here. But I didn’t see him,” says this native of Málaga who is now in his sixties and introduces himself as a friend of former Paraguayan justice minister Eugenio Jacquet – the ideologue for the dictator Alfredo Stroessner.

“When comrades from Spain showed up, we would wonder what they’d done,” recalls Cordón. Under Stroessner, who fell in 1989, Paraguay protected a hundred or so far-right Spanish activists, according to Cordón. The list includes fugitives such as Emilio Hellín, who assassinated the 19-year-old student and left-wing activist Yolanda González in 1980.

In 2016, this newspaper located José de las Heras Hurtado, the brains behind a far-right group named Frente de la Juventud (Youth Front). De la Heras is a fugitive who was hiding out in a suburb of the Brazilian city of Guarujá and who, like the others, claims he is unaware of Lerdo de Tejada’s whereabouts.

“Go ask his mother or his brothers and sisters. They were very close to Blas Piñar. I’ve never seen him in Brazil,” said De las Heras, 72, who is a lawyer by trade.

De las Heras’ group was responsible for several killings and attacks, including a letter bomb mailed in 1978 to the EL PAÍS newsroom, resulting in the death of the doorman, Andrés Fraguas, and injuries to several other workers.

Fernando Lerdo de Tejada fled Spain thanks to prison leave issued by Rafael Gómez-Chaparro, then a judge at the High Court. A former member of the Franco regime’s Public Order Tribunal, he dropped the investigation amid great controversy when it emerged that Lerdo de Tejada had skipped the country. Gómez-Chaparro had extended the prison leave without first informing the prosecutor’s office or the victims’ attorneys.

Before that, Gómez-Chaparro had also allowed the instigator of the Atocha killings, Francisco Albadalejo, to attend a wedding; he had additionally issued four prison leaves to José Fernández Cerra, who physically pulled the trigger in Atocha.

Now 96, Gómez-Chaparro has memory lapses. One of his five children, a lawyer named Fernando Gómez-Chaparro, quickly reacts when asked whether his father belonged to the extreme right, or whether he worked to conceal the ties between the Atocha gunmen and the Francoist bunker during the investigation.

The attack just over a year after the death of Francisco Franco threatened to derail Spain’s fragile democracy

“My father was not part of the extreme right. He never wore the blue shirt. He simply enforced the law. The administration of Suárez approved weekend leave for prisoners. And my father observed the law. Otherwise, he would have been knowingly committing an unlawful act,” he says, adding that he he does not know whether Blas Piñar personally asked his father to issue a leave to Lerdo de Tejada, as the chroniclers of the day reported.

Lerdo de Tejada’s escape was viewed as treason among far-right circles at the time. So says Juan Antonio Larrea, a former member of the Frente Nacional de la Juventud (National Youth Front), a neo-fascist legion of 150 individuals who carried out assassinations, attacks and kidnappings during those violence-heavy “years of lead.”

“Lerdo de Tejada’s escape condemned his comrades to serving out their full sentences. The individuals involved in the [Atocha] killings had been left out of the government pardons for other prisoners with blood crimes on their hands, including members of GRAPO, ETA, and FRAP…,” notes Larrea. “The judge felt that such a pardon was unfair, and he reached a tacit deal by which the justice system would grant them the leave that the government had denied them.”

“The first one to come out of prison was Lerdo de Tejada,” he adds. “His family had the most clout, they were part of the high-class bourgeoisie. The others came from lower-class backgrounds. But his escape left the judge in such a difficult situation that he eliminated all future leave. I have heard this from several convicts: ‘Lerdo de Tejada betrayed his comrades’.”

English version by Susana Urra.

A far-right tribute to the murderer Fernández Cerra

EL PAÍS has learned that Spain’s far right is organizing a dinner tribute to José Fernández Cerra, the murderer behind the Atocha killings. “He has become a very discreet, proper person. He won’t talk to the press,” says Juan Antonio Larrea, a former member of the National Youth Front and president of the In Memoriam Juan Ignacio Association. This group organized a fascist summit in Valencia last year, and one of the guests was Edda Negri Mussolini, the Italian dictator’s grand-daughter.

In February 1980, the High Court sentenced Fernández Cerra to 193 years in prison for five murders and four attempted murders, and for illegal possession of weapons. The court ruled him to be one of two perpetrators of the Atocha massacre, along with Carlos García Juliá.

A former member of the Spanish Falange, Fernández Cerra was released on parole in 1992 from El Dueso penitentiary in the norther region of Cantabria, where he had taken up law studies and worked to obtain sentence reductions.

Fernández Cerra, who declined to speak with EL PAÍS, currently resides in Alicante and is listed on the business register as the sole administrator of a home renovation firm and a wholesale company.

His comrade Carlos García Juliá, who was sentenced to 193 years, got a judge to allow him to travel to Paraguay while on parole, on the excuse that he had a job offer from a shipyard. In 1994 a court ordered him to return to Spain, but he ignored the order. Two years later he was arrested in Bolivia on drug trafficking charges and sent to a high-security penitentiary in Palmasola (La Paz).

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.