Decoding the secret messages of Spain’s Alhambra palace

Spanish team translates 10,000 inscriptions at the UNESCO World Heritage Site in Granada

Propaganda has always been a potent tool for the powers that be. In 13th-century southern Spain, or Al Andalus, under Muslim rule, the Nasrid dynasty made full use of it, spelling out its messages in ornate engravings on the walls, columns, arches, fountains and ceilings of the magnificent Alhambra Palace and gardens complex in Granada.

Thanks to the painstaking work of a Spanish academic, we now know that most of the 10,000 inscriptions adorning the city are not, as was once thought, just snippets of poetry or extracts from the Koran, but are also references to conquests and other feats.

It’s hard to find an inch that is free from inscription in the Alhambra

José Castilla Brazales, researcher

But the most common engraving is the Nasrid motto “Wa-la galib illa Allah”, meaning: “There’s no greater conqueror than Allah,” a reminder to mortals of who was in power.

So says Juan Castilla Brazales, an expert in Arab history and culture at Spain’s elite CSIC School of Arabic Studies, who has catalogued most of the epigraphs with the help of a team of 12 aides after a laborious process that involved locating each inscription, translating it into Spanish and English, linking it to similar inscriptions, photographing and drawing it.

“It’s hard to find an inch that is free from inscription in the Alhambra,” says Castilla. “Even the muqarnas [decorative form of vaulting] sometimes have inscriptions on them. I’ve spent hours searching for epigraphs on the ceilings with my binoculars.”

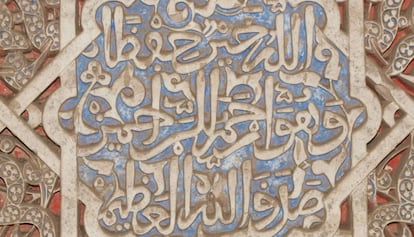

Unlike European palaces and cathedrals, Arabic décor avoids human or animal motifs. Nasrid decorations rely on geometric and floral shapes and, in the absence of sculpture, on calligraphy, according to Castilla.

“The Alhambra is not covered in poems or Koranic verses, because one of the main goals of the décor was to reinforce identity,” he says. “It was a kind of advertising.”

Hence there are frequent references praising Allah, such as “Thanks be to Allah” or “Glory to Allah”. To a lesser degree, there are brief inscriptions promoting abstract concepts such as happiness and glory, as well as blessings and phrases lauding the monarchy. Last of all, there are inscriptions from the Koran and poetry from some of the most brilliant scribes of the age.

Juan Castilla and his team are now celebrating the completion of a work 500-year-old work in progress: after the Christian conquest of Granada in 1492, and with it the end of Arab rule in Spain, the Alhambra attracted sightseers intrigued by the meaning of the inscriptions. Translations were made of many of the poems, but not of the smaller epigraphs. The first attempts were made by local physician Alonso del Castillo in 1564.

But Castilla wanted to complete the task, leaving no stone unturned. “I wasn’t content with just the inscriptions that are in plain view. I sought them all out.”

Geometric inscriptions

The inscriptions in the Alhambra are written in classical Arabic, making them difficult for someone only familiar with modern Arabic to read. “It’s an ornamental calligraphy with floral flourishes that make reading it harder,” says Castilla.

There are three types of letters – Kufic, from Kufa in Iraq, was the first and is considered sacred due to its historical role in copying the Koran. It was swapped for italics until Granada's artisans came up with a geometric form, which, according to Castilla, suggests a creative maturity in Andalusia's most valuable contribution to Islamic art.

He found inscriptions in cellars, under stairs and in places that hadn’t been touched for centuries. Asked if there is a link between each inscription and its location, Castilla explains that each sultan wanted to leave his mark and designed spaces according to the chosen epigraph. At times, quotes were invented for the occasion and in some other cases, familiar texts were used.

The catalogue of inscriptions has been collected in the Epigraphic Corpus of the Alhambra, a set of eight bilingual books and interactive DVDs that explain the ins and outs of each inscription – its location, translation and context, accompanied by photos and drawings.

The Spanish University Publishers’ Association has just awarded the translations the distinction of being the best national book edition in digital format. Reynaldo Fernández, director of the Alhambra and Generalife Trust and publisher of the work, hopes to have the final two book-DVDs on sale during the first half of 2017, thereby bringing to the light of day the last of the Alhambra’s secrets.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.