Spain observes 30 years in EU club amid growing euro-skepticism

Austerity measures have blurred many people's appreciation for decades of benefits from development funds; the time has come to reflect on how far the country has come since it joined, and what its future commitment to the union is

The first history lesson that aspiring diplomats at the College of Europe in Bruges used to receive always took place in the countryside. “I got there in 1973,” recalls Manuel Marín, former Vice-President of the European Commission and a key negotiator of Spain’s accession. “The first day of class, we were taken on a bus to a small hill overlooking a vast cemetery that was established there after World War II. Our teacher, Mr Lory, pointed out the endless rows of white crosses and said, ‘If Europe exists, it's because of this’.”

The 30th anniversary of Spain’s admission into the European club is being observed with a low-key official event rather than festivities and fanfare, as though it were nothing more than a calendar date.

Of course, the anniversary finds the European Union in turmoil following Brexit, internal conflicts and a faulty design, not to mention the resurgence of nationalism and populism and the growing threat of wars along its borders.

The question of what Europe has to offer its members is being asked everywhere. Hurt by the brutal austerity measures, Spaniards have become absorbed in domestic problems and are largely unaware that their future is going to play out in this supra-national stage – the same one that, 30 years ago, provided Spain with the springboard for a social and economic leap forward that helped restore the country’s self-confidence.

It was a great boost to national morale because it meant that the country was finally returning to normality

Eugenio Nasarre

The original dream of a free federal Europe did not originate in chancelleries or university cloisters, or during debates among the military elite following World War II. Rather, it was inspired by the vision of the Italian journalist Altiero Spinelli when he was deported to the island of Ventotene for questioning dictator Benito Mussolini’s rise to power in Italy.

In June 1941, horrified by the extent of the slaughter, communist sympathizer Spinelli wrote the manifesto for a free and united Europe on onionskin paper in very small handwriting. His vision would lead a decade later to Europe’s Coal and Steel Community, which was the precursor to the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Union.

Spinelli’s call for “the definitive abolition of Europe’s division into separate nation states” and the creation of “an international force” that would guarantee people’s rights and put an end to totalitarianism and the ideology of national independence had a revolutionary ring to it, but the 60 million dead from WWII made it imperative to find a way of avoiding a third global conflict, and this seemed the most sensible solution.

After the Allied landings in Normandy, French Resistance figures Pierre Mendès France and Charles de Gaulle began to consider the idea of creating a European core made up of France, Italy, Belgium and the Netherlands. “Spain will join later when they get rid of Franco,” they predicted. It was the summer of 1944 and nobody imagined that it would take another 30 years before Spain was free of the dictator.

According to Manuel Marín, Spain’s integration into the EEC brought with it two feelings that are rarely seen in Spanish history: the feeling that something epic was happening, and a collective sense of self-esteem. In Marín’s opinion, only the winning goal scored by Iniesta in the South African World Cup of 2010 has ever come close to producing a similar wave of enthusiasm.

Surveys show that a third of Spanish voters on the left think that Europe has done more harm than good

“It was a great boost to national morale because it meant that the country was finally returning to normality,” adds Eugenio Nasarre, president of the Spanish Federal Council of the European Movement, and former head of the state broadcaster RTVE.

“Previously, we had envied other students from European universities – the freedom with which they spoke out and thought and lived. We wanted to be like them. Europe meant freedom,” says José María Gil Robles, a former speaker of the European Parliament.

Surveys show that a third of Spanish voters on the left think that Europe has done more harm than good. And they are not alone. Now that the EU has become the scapegoat for our problems, a lot more people are wondering if membership has really been to our benefit.

It’s not the right question to ask, first because the answer is obvious – Spain is the country that has benefited the most from European grants – and second, because it ignores the responsibility each member should shoulder for the well-being of Europe; and third, because it fails to question what Spain has brought to the table.

The Spain of 30 years ago was a country of black-and-white with two TV channels, dreadful roads, laughable communications and a largely obsolete industrial sector. It was a country that didn't have electricity in rural areas and whose farmers lacked social security; a country that was still arguing about the right to abortion; a country that was dogged by an inferiority complex and celebrated any success in sport, however small, as if its life depended upon it. Its average per capita income was not quite 72% of the European average – today it’s 94% – and its productivity was scarcely 50% of the EU average. Thirty years later, GDP has doubled, from €461.4 billion to €921.7 billion (2013) and the country’s exports are up eightfold.

We were welcomed with much emotion because of the drama of the Spanish Civil War, which was the harbinger of what was in store for the rest of Europe, and the dictatorship

Enrique Barón, ex European Parliament president

As for infrastructure, Spain has gone from having 483 kilometers of highway in 1986 to nearly 14,000 kilometers today, with 40% of these 14,000 kilometers funded by the EU. Europe has made an important contribution to the 2,500 km of high-speed train tracks and the modernization of airports; it spent €2.4 billion on Terminal Four in Madrid’s Barajas airport and €1.1 billion on the expansion of Prat airport in Barcelona, as well as investing €41 billion on the restructuring of Spain's financial sector. There is no sector in fact, whether economic, industrial, health, social or cultural, in which the EU has not intervened with grants, loans and other forms of financial help.

Between 1986 and 2013, Spain received €151.4 billion from the EU, and that’s without counting the €45 billion that has been earmarked for Spain until 2020.

In return, our country contributes the obligatory 1.24% of its GDP. Although the spectacular growth of the Spanish economy in the last 30 years, together with the admission of much poorer countries from Eastern Europe, has notably reduced the amount of money allocated to Spain, it is still a beneficial relationship, economically speaking.

“Europe has been the vitamin pill that enabled us to modernize at high speed,” says José María Gil Robles. “In the first 25 years, we received double the money we put in, and now, thanks to our development, we are starting to become net contributors.”

Regions such as Extremadura, Andalusia and Melilla, however, continue to be net beneficiaries of EU grants because their GDP is below 75% of the EU average.

Socially speaking, the changes are equally impressive. In 1986, life expectancy in Spain was 76.4 years. Today, it is 83.2 years.

Enrique Barón, former president of the European Parliament and the Socialist Party representative at the commission that hammered out the Spanish Constitution in 1978, confirms that all Spain’s political parties agreed during the Transition that democracy and European membership went hand in hand.

In June 1977, Suárez’s first government applied for membership, and the fact that there was general consensus on the issue facilitated Spain’s entry into the Council of Europe – an institution reserved for member heads of state – even before negotiations to join had begun.

Barón recalls the excitement of that first meeting with the European leaders. “We were welcomed with a lot of emotion because of the drama of the Spanish Civil War, which was the harbinger of what was in store for the rest of Europe, and the dictatorship,” he says.

According to Barón, Spain was constantly being championed by Jacques Delors. “He told me that they would probably win the elections and that if they did, he would call Mitterand – then the French President – and do everything in his power to get Spain into the European Community.”

On June 12, 1985, during the ceremony for Spain’s official entry, which became effective on January 1, 1986, then-European Commission president Jacques Delors declared: “We have missed you. The building of Europe and its aspirations would have remained incomplete without your membership and participation.”

After the warm welcome, however, Spanish delegates discovered that their European counterparts were hard nuts to crack. “According to their calculations, we practically had to pay to enter. It was a massive shock and we rebelled,” says Baron. “The talks between German Chancellor Helmut Kohl and [then Spanish prime minister] Felipe González were crucial because structural European funds were doubled twice – once in 1987 and again in 1993 – with positive results for Spain.”

We are emerging from the economic crisis, albeit by an inefficient and socially painful route, but we will not emerge from the refugee crisis without opportune foreign and security policies

Former PM Felipe González

Felipe González himself considers that that agreement was one of three key moments in the development of Europe for Spain, together with the Maastricht treaty and the euro.

But before joining, the Socialist leader had to get the UK and France to lift their vetoes against Spain. “The European Council of Stuttgart in 1983 was decisive,” explains Manuel Marín. “Kohl, the German chancellor, managed to win Margaret Thatcher and François Mitterand over, by paying off one and offering an agricultural fund to the other. In return, Felipe González had to agree to host euro-missiles and a contingent of US troops on European soil because Germany feared that the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union threatened peace on the continent. It sounds drastic now, but in that context it sounded perfectly logical.”

Were NATO and US missiles the price Spain had to pay to join Europe? According to Felipe González, that wasn’t the whole story. “I felt Spain would be better defended and represented that way. But I want to remind people that the referendum on whether we remained in NATO was held after we joined the European Communities. So it wasn't a condition as is so often suggested. I pushed for things to be done like this.”

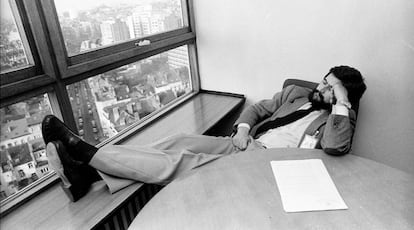

Although the negotiations for Spain’s entry were formally finalized on March 29, 1985, the loose ends were not tied up until June 6 of that year. And a photograph that shows Manuel Marín having a nap between rounds of negotiations gives some idea of how exhausting those talks were. The photo illustrated the tenacity of the Spanish delegation and became symbolic of the French minister Édith Cresson’s observation that the prolonged debates that continued into the small hours suited Spain.

“We were very young and we could put up with long days engaged in tugs of war,” recalls Marín. “The first thing we discovered was how difficult it is to have a global vision. We had specialists in almost all areas but we were on shaky ground because at that time the national Institute of statistics did not exist, so we had no official data to fall back on.”

There was a flight from Brussels to Madrid that Marín remembers vividly. “I held in my hands a letter in which the commissioner for industry, a Belgian called Étienne Davignon, told Felipe González that our steelmaking sector was outdated and would have to be either done away with or reformed,” he recalls. “I was thinking about the Altos Hornos de Vizcaya factory, about Babcock & Wilcox, about Sagunto and Avilés… and I was really afraid. The industrial reform was huge. It brought with it the first general strike, but if Spain today has a great auto export industry it is because we tackled these reforms.”

According to Marín, the obligations forced upon Spain by Europe were decisive in the modernization of its industry. “We would never have done it of our own accord, nor would we have established VAT,” he says, before going on to list additional benefits: “If, today, Spain has the most protected areas in Europe, it is thanks to guidelines from the Habitats conservation directive. We would also do well to remember that until the fall of the Berlin Wall, we received 1.5% of our GDP from Europe and, only a few years after joining, we were the second-biggest beneficiaries of grants to modernize agriculture and the biggest beneficiaries of structural funds.”

Were NATO and US missiles the price Spain had to pay to join Europe? According to Felipe González, that wasn’t the whole story

In spite of the advantages Spain has had, the country maintains a purely utilitarian view of the EU, which remains a distant entity with only vague relevance. Despite signs emblazoned with “Financed by the EU” strewn across the country, many Spaniards still demand to know what good can come from membership. Then there are those who show an ignorant disdain for what has been achieved so far and for the future goal of establishing a supra-national democracy with a social market economy that is, by its very nature, always unfinished and incomplete.

But there is another important question to ask and that is, what has Spain contributed to Europe?

“Hope, momentum and a decidedly pro-European vision,” says Joaquín Almunia, a left-leaning Spanish politician who was formerly a prominent member of the European Commission. “Our officials and civil servants were a strong presence from the outset in 1986 and they made a reputation for themselves as people who were dedicated and well qualified for the job. That’s where descriptions such as ‘the Prussians of the South’ came from. We brought the Latin American dimension, the concept of European citizenship with the right to vote and a bill of basic rights as well as policies of geographical cohesion that the Eastern European countries are now benefiting from. This was something that Felipe and Delors fought for together until they convinced Kohl. Recently, they speak about the Spanish model when managing migration agreements with neighboring countries. But we also bring a scandalous rate of unemployment and more recently, a notable lack of presence. We’re too busy navel-gazing.”

Under the leadership of former conservative Prime Minister José María Aznar, Spain met the criteria set out by Maastricht and joined the euro zone. But more recently there is a feeling that Spanish governments have been disconnecting from Europe and that we have lost clout on the continent.

“We were respected because of our capacity for deal-making,” says Marín. “And because we were able to quash stereotypes about Spain, such as the ‘mañana’ attitude and our confrontational nature. The problem now is that we have lost our feeling for making pacts. Politics has been brutalized and a return to the European debate is difficult, if essential. What we need is a solid government with a shared position. To be seen as the poor relation of Varoufakis [former Greek minister of finance] would be a disaster. You can’t go around like Captain Thunder while wielding a plastic sword.”

The former director general of foreign relations for the EU, Eneko Landaburu, explains the change in attitude toward Europe in terms of his personal experience. “When Felipe González sent me to the EU, he said, ‘Eneko, we are not going as beggars, we are going as members. This is about being at the forefront of the creation of Europe.’ With [former Socialist Prime Minister] Rodríguez Zapatero things changed. At the beginning, he would be on the phone for half-an-hour asking about Europe; then it was five minutes, and then he became more interested in ETA. In recent years, Spain has brought nothing to the EU.”

Thirty years ago, when Felipe González signed the membership papers, he declared that Spain had to offer “the wisdom of an old nation and the energy of a young one”. Today González says: “There have been changes in the attitudes of Spanish officials, and we have been losing clout and relevance in the EU to the point that our absence in the process is so noticeable as to be absurd.”

“Germany is awash with conductors for this particular orchestra and there are not many countries that want this role,” says Almunia. “France is in the middle of a huge crisis and we saw with its previous president, Sarkozy, that after several initial overtures, it abandoned the role of joint leadership. Number three, which is Spain, is looking inwards. Italy is beginning to have a presence and at times it seems that Poland might gain more influence than us. Who would have sorted out the financial crisis and the refugee problem if it hadn’t been for Germany? Every time Germany makes a mistake, we have a problem, so there clearly needs to be someone to counterbalance their power.”

This counterbalance could only come from a renewed commitment from countries that are truly pro-European and willing to give fresh momentum to the union, to take it beyond the reach of the populists, the Europhobes, and the big state egos.

“There has to be a clearer governance and more democratic representation,” says González. “We are emerging from the economic crisis, albeit by an inefficient and socially painful route, but we will not emerge from the refugee crisis without opportune foreign and security policies. To top it all off, we have resigned ourselves to the disintegration of the social market economy, a strategy that defined the European model that aimed to counter unsustainable social inequalities generated by globalization.”

Today, just as 30 years ago, the Spanish dream is inseparable from Europe, just as Spanish interests are inseparable from those of the EU. And survival instinct alone prompts the question of how Spain can help bolster the federal dream.

“Far from being part of our problem, Europe is most of our solution,” says Landaburu. “And this should be the main topic for debate in Spain.”

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.