Just 12 words for each dead body

Opacity of Mexican operation against drug gang raises more questions than it answers

The official note is headlined “Military personnel repel an assault,” and says that the events took place at 5.30am in Cuadrilla Nueva, a small village in a remote corner of southern Mexico State.

A military convoy was conducting some ground inspections and chanced upon a grocery store being watched by “armed personnel” who began firing when they saw the soldiers. In the end, 22 alleged attackers were dead and one soldier lightly wounded. The release goes on to say that three women were released after being allegedly kidnapped. No identities are provided, no explanation is offered as to which gang the dead men belonged to, nor is it clear what the army was doing there at such an early hour of the morning.

The official explanation for the killing of Cuadrilla Nueva, which took place early Monday morning just a two-hour drive away from the federal capital, uses no more than 273 words to inform about a bloodbath that in other places would have raised a thousand questions and triggered as many explanations.

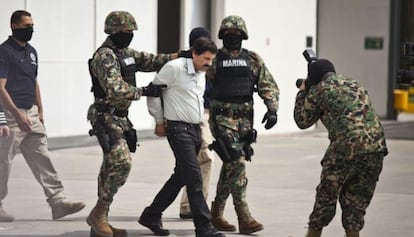

With so much publicity for sting operations, even the criminals began turning into legendary figures

But in Mexico, where police officers die at the hands of drug dealers on an everyday basis, no political party has been moved to action. To many, this is just the latest episode in an ongoing war that is always there in the background. In this case, the gang in question was the Guerreros Unidos (United Warriors), a criminal organization born out of the ashes of the Beltrán Leyva cartel, and now furiously at war with Mexican authorities.

“The fight remains strong in states such as Tamaulipas, Michoacán and Guerrero, where the narcos are a powerful presence,” notes Alejandro Hope, a former official at the national intelligence service, Cisen. “Confrontations of this nature take place there. As in the past, we are left with the lingering question of what really happened. Even the official story begs all sorts of questions. It says, for instance, that two women died and three others were freed after being allegedly kidnapped. It bears asking whether the dead women were also kidnap victims. But no-one will ever know, and in the end nothing will happen.”

Part of the opacity around these operations against the drug gangs stems from the use of army personnel to do police work. Between 30,000 and 40,000 servicemen have been sent to the front. This deployment is due to the fact that the army is less tainted by corruption than other armed forces, and especially to the fact that they are the only ones with the ability to fight criminal groups in possession of high-powered weaponry.

“But there is a problem with this: sometimes the army uses disproportionate force, turning the matter into military combat, rather than a police operation,” says Hope. Or, as the National Human Rights Commission notes, “the armed forces do not simply act as a support for civilian authorities, but perform duties that fall exclusively to civilian authorities.”

The UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Executions has warned of the harshness of the “military repression”

This military control has raised many alarms, even outside Mexico. After a recent visit to the country, the UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Executions, Christof Heyns, warned about the harshness of the “military repression” and the absence of accountability for abuse. Heyns’ report talks about “systematic and endemic impunity,” not just because the military are tried in their own courts in cases of crimes against civilians, but also because the judicial system has become a black hole where “only one to two percent of all crimes, including homicides, lead to convictions.”

Experts consulted for this story said that the deaths at Cuadrilla will show up in national statistics not as homicides, but as deaths resulting from legal interventions and war operations.

As well as this general opacity, there is also the new minimalist tone adopted by the Enrique Peña Nieto administration with regard to the war against organized crime. During the last six years, this issue became the backbone of the government’s program, with every operation and arrest exhibited before the public. But strategists for Peña Nieto feel that there was overexposure. “All talk of narcos was being linked to Mexico, and even the criminals began turning into legendary figures,” notes one high-ranking official.

The government decided to put an end to this celebrity status by staying silent about the war against the drug gangs. Official sources admit that only the bare minimum information is shared, that press releases are as short as possible, and that even the name of the cartels is omitted. As a result, public perception of security has improved, but at the cost of a silence so intense that 22 deaths in Cuadrilla Nueva have been reduced to four paragraphs.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.