Electricity sector on standby as ministry grapples with funding gap

Finance's refusal to cut budget slack to plug tariff deficit delays plans for industry overhaul Consumers can expect higher bills

At the beginning of last week Alberto Nadal, Spain's secretary of state for energy, made a statement of intent on energy sector reform. Nadal, speaking at the summer school run by the ruling Popular Party's FAES think-tank, outlined the sector's main problems, as well as the government's objectives. But he gave no details on the overhaul itself, which to date already includes several decrees and a white paper that should have been approved by the end of June, but that has been delayed by disagreements over costs with the Finance Ministry.

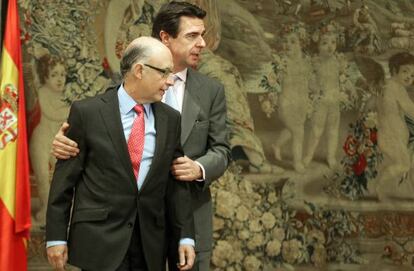

The plan now is for the Cabinet to approve an energy-sector reform at one of its upcoming weekly Friday meetings, an event that might well be left until after the summer break. The conflict is over the need for greater funding from the state budget, while the man whose approval is needed, Finance Minister Cristóbal Montoro, has refused to budge, saying "there is very little margin" if the government is to comply with the stringent rules laid down by Brussels to reduce the country's public deficit.

Industry and Energy Minister José Manuel Soria inherited a problem which has been left unresolved by successive administrations: the so-called tariff deficit. The deficit dragged along by governments of different stripes is the difference between what it costs to generate power and what can be charged to consumers by suppliers in rates regulated by the administration. According to figures released earlier this year by the National Energy Commission (CNE) sector watchdog, the tariff deficit at the end of 2012 amounted to 4.281 billion euros, well above the administration's initial goal of 1.5 billion.

Since his appointment at the start of this year, it has fallen to Nadal to come up with an answer to this Gordian Knot. His reaction was to set the counter at zero and come up with a solution from 2014. This meant that 2013 would be an effective vacation to be dealt with by budgetary measures. To deal with the deficit over the last year and this, a series of measures were adopted that cost 10.178 billion euros. Of this, 3.955 billion was drawn from the state budget. The remainder was garnered from the sector.

The tariff deficit has been dragged along by governments of different stripes.

Speaking on July 1, Nadal said that if these measures had not been taken, the deficit would have reached 10 billion euros; despite them, it still stands at four billion. To eliminate the debt "would mean increasing the tolls by more than 30 percent, which would mean increasing electricity bills by 17 percent." But it's clear that he's not going to make consumers pick up the entire tab. "We will take reasonable measures, adjusting the contribution by all stakeholders in the system based on common sense, bearing in mind the situation in the country, the economic cycle we're in, and what each can manage, trying to reach a reasonable level of profitability," Nadal said, adding: "The reform will be, above all, a law about financial stability in the electricity sector, which will prevent changes in the rules of its functioning, with no extra costs, and which avoids any reappearance of the deficit."

The reasoning behind the equation is not hard to understand; but the repercussions, mainly political, will make it hard to square the circle. The government wants to "guarantee the supply and quality of electricity at the lowest cost possible." The root of the problem lies in regulated costs and that earnings are not even enough to pay for the costs of the system. Earnings are 18 billion euros (14 billion from tolls and four billion from fiscal earnings) while costs have risen to 22 billion (nine billion from renewables and cogeneration; seven billion from distribution and transport; 2.5 billion from the previous deficit; 1.7 billion from costs outside of Spain; and 1.8 billion from others).

Spain's electricity deficit is the result of a policy by previous governments of subsidizing the promotion of renewables, including high feed-in tariffs to power generators. But the main contributor to the deficit has been a policy of keeping consumer rates low even as supply costs climbed, so the true costs were never passed on to the user.

The government has now proposed new measures to address this situation, including taxes on generation and nuclear waste; a levy on hydroelectric energy; a special tax on gas; a "green cent" tax on coal, as well as on gasoline and diesel used to produce electricity; all along with a drastic cut in subsidies for new clean energy projects. To cover the cost of this, the utilities want to bundle the debt into securities that will be sold to investors, to be paid by consumers in future electricity bills.

Eliminating the debt would mean increasing electricity by 17 percent"

The goal is to balance incomings and outgoings and to share the costs between all stakeholders (renewable producers, utilities and consumers) and the budget. This would be done proportionately to current costs, meaning that consumers would have to pay 300 million euros; between 400 and 500 would come from the distribution and transport sector; 800 would stem from renewable premiums and 2.2 billion from the state budget.

According to sources in the sector, the best approach would be to remove from electricity bills the extra costs that have nothing directly to do with electricity generation or distribution and that currently make up almost half of users' fees.

"That argument is technically correct, but if you remove those charges from the bill, then they have to be paid for out of the budget," says one analyst. More to the point, the Finance Ministry says that there is no margin to do this - and this is the source of the disagreement between Montoro on one side of the cabinet table, and Soria and Nadal on the other.

Whatever decision is reached, Nadal will come out of this looking like the bad guy. He has already been pressured by a range of business lobbies. Until now, the utilities have been fighting among themselves and complaining about how unreceptive the secretary of state for energy is being as he has refused to be drawn on the planned reforms. The utilities want to know what sense there is in overhauling the sector without asking all the stakeholders for their opinion. "It is true that we have said what we think, but that doesn't mean that anybody is listening," says one source at a major utility. For the moment, the main electricity companies have stopped investing as they wait to see what happens.

That said, the Spanish electricity sector works reasonably well, with a sufficiently diverse energy mix, although perhaps the renewables sector is somewhat over-capacitated due to investment that went beyond the objective of it making up 20 percent of the mix by 2020: it now makes up 35.9 percent of power generation.

"What's the problem?" asks Nadal. "The problem is that it is expensive. It is expensive because certain decisions were made - let's say over the last 10 years, so as not to point the finger at anyone in particular - meaning that the system was forced to absorb certain costs that it shouldn't have had to absorb. The outcome of which is that Spain has had to deal with a much steeper learning curve than the rest of the world and that has left it with a 25-year mortgage."

Nadal has put his finger on it. Because it was the previous Popular Party government that in 2000 approved the deficit mechanism, while José Folgado, the current head of the national grid, was in charge of the Energy Ministry. The Socialist Party administration that came to power in 2004 then poured more fuel on the flames, and thanks to its overly generous policy of supporting renewables, sent the deficit soaring. Until 2005, when the greening approach was put into place, the deficit was 6.274 billion euros, and access tariffs were sufficient to pay for regulated costs. But the regulated costs have risen sharply over the last five years, and by the end of 2012, the accumulated deficit was already 26.671 billion euros, of which 8.944 billion euros will remain off the utilities' books, according to sources at Unesa, the body that represents the electricity companies.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.