A step away from death

They are a deserving club of survivors. In the history of the United States, 139 innocent people have been rescued from death row, a place to which they should never have been sent. EL PAÍS Semanal magazine had access to a private meeting of 21 of them in Birmingham (Alabama) in 2010

"On July 7th, a judge let me out after 21 years, locked away in Illinois. I spent 13 years on death row because of a false tip-off and a confession that I signed after 39 hours of police torture. My name’s Ronald Kitchen.”

— “Good morning. My name’s Curtis McCarty. The State of Oklahoma unjustly condemned me to death. I was imprisoned for 22 years. Nobody’s compensated me or said they’re sorry.”

— “I’m Greg Wilhoit from Sacramento (California). I spent five years on death row. I’m happy to be here today.”

Birmingham (Alabama, United States). We arrive at the outskirts to the south of the city on Highway 65. At a crossroads, two men on a billboard advertise pizza at $5.99. Three blocks away, the road rises steeply and we arrive at the Alta Vista Hotel, from which the entire city is visible. The premises, a white

mass of color, constructed in the 1980s, has the feel of a place that has known better days and entire buildings have closed down around it, because - they say - of the economic crisis. Alabama is the fifth poorest state in the country and the truth is that it’s plain to see.

The hotel is almost empty, perfect for a calm meeting. Forming a circle in the conference room, one by one, 21 of the 139 ex-death row inmates who have managed to prove their innocence in the history of the USA introduce themselves.

Alongside the eleven black men, nine white men and an exonerated Latino are their relatives, friends and five activists from Witness to Innocence, an NGO from Philadelphia that organizes the meeting. It was founded five years ago by the religious, Helen Prejean; the woman brought to life in 1995 by Susan Sarandon in the film Dead Man Walking. A total of 47 people each take turns to talk, and speaking out aloud, they introduce themselves to each other. For the group, from all over the USA, this is the chance for some to find each other again and for others to meet up. For all of them, it is an opportunity to “recharge their batteries,” a kind of five days collective communion, “a reunion of old students,” as some joked.

It is their private moment after a year in which some of them have not stopped traveling and campaigning against the death penalty in schools, universities, churches... Exceptionally, they allow a mass media organization, “as it is from abroad”, to join their intimate forum for the first time. Some of them, such as Curtis McCarty, mistrust American journalists: “If they would pay more attention to the death penalty in our country, if they would say that there were unnecessary, immoral and unconstitutional things about it; they would put an end to the problem. But they don’t.”

THE CIRCLE WIDENS IN SIZE: 48 and 49, a journalist and a photographer from EL PAÍS Semanal come into the meetings and share the hotel, its food, and drink and multiple conversations over five days in November, in Alabama. The place chosen by the NGO (each year they choose a different one) stands out because it is one of the States in which blood flowed in the fifties and sixties, for the sake of racial equality in the United States.

Situated in the south of the country, Alabama conserves all the heritage of its segregationist and religious-fundamentalist past, which it’s shared with other States such as Texas, Florida, Oklahoma, Missouri, Georgia, North and South Carolina, Louisiana, Arkansas...

It is not by chance that these southern regions are also those in which the great majority of executions take place in the United States; 87% of the total in 2009. But those are deaths which generate no social debate. We find out as much in Alabama. The only moment at which the exonerees and their families left the hotel in five days was to flock to the entrance of Birmingham’s Palace of Justice, where they had organized a press conference.

On a pleasant sunny day, only two communications media turned up: ABC television news and El País Semanal. Hardly twenty passers-by stopped to listen.

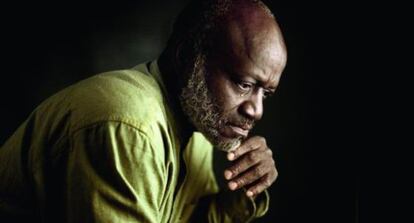

We speak to the exonerated prisoners from death row one by one in the hotel. In an adjacent room to the one used for the meetings, we interview and picture them. Sharing some old brown sofas next to large windows, these 21 people explain their miracles and guide us through the penitentiary, judicial and police system in the United States. The trickle of testimony paints a general situation full of common places: corruption, ill-treatment, after effects, racism... Bit by bit we see the faces of the horror. Derrick Jamison’s is unforgettable. This 48-year-old Afro-American from Ohio with the appearance of a rapper looks into the camera. He smiles patiently, gold teeth, rings and all sorts of cheap jewelry shining brilliantly.

His Cincinnati Reds baseball hat reveals his origins and his liking for the sport.

We also speak with him about basketball. He says he is a fan of LeBron James and his Cavaliers, from Cleveland, the other large city in his state. Derrick is a person who awakens kindness when he speaks, he does it slowly, like a child in an adult’s skin, with a strange peacefulness that surrounds almost everybody saved from death row. As if they were already over the suffering, which Derrick overcame and knows well: “I was only one hour from being executed, only one hour away from death, one hour from being murdered; because that is what they wanted to do. Do you understand what I am saying to you? I was only one hour away from being killed,” he says with a fixed gaze. It was the worst moment of his 17 years on death row, the most critical day of his life, his expiry date.

In 1985, he had been accused and condemned to death for the murder of a bartender in his city. But Derrick maintained his innocence at all times. In his way to prove it, he had to struggle against a lazy appeals system. They went so far as to offer him life imprisonment if he confessed to the crime.

He did not plea bargain. He couldn’t, despite living day to day with the threat of his own legal assassination, because he knew he was innocent. The judicial process dragged on and was so slow that he had to wait until 2002 for a judge to decide that he had to be tried again and to free him from death row. Two things then became apparent: another accused person with a dubious record had had his sentence reduced in exchange for testifying against Derrick, and the prosecutor had intentionally withheld vital statements from various eye-witnesses to the crime that contradicted the grass’ false statement. In short, there was never any evidence against him. Jamison was finally freed in 2005. Twenty years after: innocent.

He has received no compensation.

Derrick, who describes his first day on the street “like a child’s on the day before Christmas,” was very lucky. He belongs to the club of 139 prisoners (only one woman among them and a Spaniard, Joaquín José Martínez) freed from death row, a place to which they should never have been sent. Despite that misfortune, they generally consider themselves lucky. According to the most conservative figures, at least eight innocent prisoners have been executed since 1976, when the death penalty was reinstated in the USA following a four-year pause, due to the case of a convict in Georgia that went as far as the Supreme Court.

Since that last great opportunity to do away with the death penalty, the USA has used various methods to put 1,188 people to death. The figure is up until last December 29th, but the deaths continue, as lethal injections and electric chairs do their work. There are macabre calendars on the internet with upcoming execution dates, names and last names. Six deaths are expected in January 2010; three in February... the USA is the fourth country in the world behind China, Iran and Saudi Arabia with the most executions.

THE ABOLITIONIST MOVEMENT in the USA has greater merit because it’s fighting an uphill battle. “At times the battle is a solitary one, above all in the South, at the heart of the death penalty States, where it lags behind the rest of the country with regard to awareness raising. At any rate, although it was frustrating to be against the death penalty in the eighties, things started to change in the nineties because more and more cases emerged of innocent people in prison. The movement has grown,” in the opinion of Kurt Rosenberg, one of the activists present in Alabama, who took up the reins of Witness to Innocence shortly after the religious Helen Prejean had founded the organization. Although recent years have been positive, as New Mexico (2009), New York (2007) and New Jersey (2007) have all done away with the death penalty in their territories and broken a negative period that lasted 23 years (Massachusetts and Rhode Island having been the last to abolish it in 1984), 35 States (out of 50) still maintain the death penalty on their statute books with overwhelming public support. According to a recent Gallup survey, 65% of United States citizens are in favor, as against 31% who oppose it. Although the gap is still abysmal, it is, however, the closest ever since the seventies and coincides with the increase in cases of innocent people freed from prison in recent years. In 2009, nine people left death row, the same figure as in 2000, only outdone in 2003, when 12 prisoners were exonerated.

The count increases ever more rapidly, above all thanks to the proliferation of evidence in the form of DNA. The Innocence Project, an organization founded in 1992, has used this method to prove the innocence of 248 people (some on death row, others not), demonstrating over and over again that the USA has a problem. The last case was of a man sentenced to life imprisonment in Florida, freed on December 17th, after 35 years in prison, a record with regard to the imprisonment of an innocent person.

AND LIFE AFTER PRISON, WHAT THEN? Leaving prison, there are economic, social, family, and health problems... Seated in a wheelchair that appears to be too small, Paul House, a corpulent man of 48, freed in the middle of 2009, thanks precisely to the Innocence Project, speaks with difficulty. His mother, Joyce, is the spokesperson almost all the time: “I get angry when somebody says that there is medical attention on death row!” Her son, with an extremely atrophied half-smile due to the lack of dental care in prison, backs her up: “Bullshit!” Paul was imprisoned for 22 years on death row in Tennessee. The last 10, of which he was affected by multiple sclerosis, locked up 24 hours a day in his cell, where he ate and relieved himself. He could hardly move nor speak. No guard made the effort, if only for the one hour a day to which he was entitled, to take him out to the patio, handcuffed.

“He started to get problems with his balance. He thought it was because of an ear infection. But on one of the visits, another prisoner came up to me and said, ‘Mrs House, something’s up with your son. I’ve seen him holding the walls so as not to fall down.’ The next day I phoned my lawyer. It took us two years to get a doctor to visit and to diagnose his illness. So the other inmates looked after him.” Paul says gesticulating: “I know it sounds strange, but I met really good guys on death row.” After the diagnosis, his mother says, the prison only gave him vitamins and paracetamol. The legal battle for the injections that he needed was arduous. Lost time that deteriorated Paul’s health, surrounded by the indifference of the Tennessee authorities.

Eight hundred kilometers away from him, Nathson Fields, another innocent ex-prisoner, lived condemned to death in Illinois. Nate, a black man from Chicago full of energy and vitality, explains the reasons for that lack of attention and we find out that what happened to Paul in Tennessee was not a one off, but part of the prison system: “Its mentality is... why should we give you medical care if we are going to kill you anyway?.... On death row, if anything they give you a couple of aspirins.”

After having spent 18 years in prison, 11 of them condemned to death for a crime that he never committed, Nate’s mind is jammed with memories. It is his post-traumatic psychological torture: “I remember the executions each day, the friends that I saw pass by my cell on their way to their death. I recall being in the visiting room and seeing one of my friends saying goodbye to his mother and children, all of them crying because there were only two days left before his execution. Some went crazy. They couldn’t stand it. They were speaking to themselves. They stopped washing. Others committed suicide. One day, one of them told me: ‘Nate, I am going to miss you.’ I didn’t understand a thing. The next day they found him hanged. Another time, a man collapsed in the patio. We asked for a doctor. Nobody did a thing. He recovered... but they did not take him for a body scan. And guess what? A month later he died of an aneurysm.”

Clearly prison made Nate stronger. He cries when he remembers the day that they told him his mother had died: That day he thought: “this is it, this is my end.” But even after that he was able to pull himself together. He did not give way under the pressure of waiting for the inevitable: “I don’t know how I managed it. I think I had the strength to resist it because I knew I was innocent. I was a champion wrestler in high school. I grew up fighting.”

Family, friends, religious faith and reading are other crutches for the 21 from Alabama. Other prisoners cannot stand it. Since 1976, 11% of all executions have been voluntary, inmates that could not go on and renounced their right to all appeals. Two cases are expected in January 2010.

ANOTHER PERSON HARDENED BY PRISON is Curtis McCarty, white, with a goatee beard, clear eyes and a shaven head. He spent 22 years in prison, 16 on death row in Oklahoma. That is a little less than half of his life behind bars. Despite having been on its fringes for so long, each comment he makes demonstrates his knowledge of American society. His story, his look and his tears hit us: “You should see what happens to these guys when their time’s cut short, when they tell them they’ve got to pack up their things to send them off to their families, because their execution’s just round the corner.”

On the wall, the calendars mark the days left for each one, an intolerable psychological tick-tock. They know their exact date a few months before: “They killed my best friend. Billy and I shared a cell for the last 11 years of his life. He was a good kid.” When Curtis talks, it is interspersed with silence, while he looks for the words that in reality he knows all too well. He is a person with two sides. His heart is suffering, but at the same time he is a happy man, who laughs and has a great sense of humor. In fact, it is a great pleasure to share beers with him and his girlfriend, Amy. While she speaks, he doesn’t stop taking photos with a small camera, as if he wished to document each instant of his life so as not to forget it. In fact, he acknowledges that he has problems remembering things, one of the consequences many of them have after spending years without any everyday jobs as simple as paying a bill.

But Curtis turns serious and cries when he reveals his most severe memories. “When they killed Billy, my time ran out too. I wasn’t in the mood for any bullshit from anybody. Some prisoners thought of going on a hunger strike to protest. They were going to kill us anyway. Fuck you, you can’t treat us like this,” he thought. At the lowest point of his anemia, a stroke of luck got him out of death row: the FBI was investigating irregularities at the police laboratory in Oklahoma City. An anonymous informer had sent in a list of eight cases to the federal police, among which figured his case, for them to reopen. It became clear that the laboratory had falsified proof for years, and thanks to the DNA, Curtis was able to prove his innocence. Asked whether he loves his country, he falls into a stony silence, touches his goatee beard, looks out at the horizon and murmurs decisively: “No.”

THE NATIONAL ANTHEM of the United States speaks of “the land of the free,” but paradoxically few Americans have been compensated for the judicial errors that had them imprisoned. After years in limbo, some are in debt, most have zero or difficult job prospects, others are alcoholics and all of them suffer from post-traumatic stress. Despite this panorama, governmental help is minimal and almost all the support is used as a lifeline for family networks and friends.

“I have spent 220,000 dollars on lawyers. I sold my house, my farm, my cars. Everything I had, even my relatives mortgaged their homes,” explains Randall Padgett, an innocent ex-convict, on death row in Alabama for five years. We speak to him in front of the entrance to Birmingham’s Palace of Justice.

He smiles because he is no longer in prison, but explains he is now ruined by the debts contracted from his stay on death row. But the truth was that either he spent the money on his own lawyers, or he would perhaps have died. The state-appointed lawyer acknowledged that he was not going to put up much of a fight. It was a case in which he was hardly going to earn a few dollars.

Finding a job is very difficult for Randall and the others, today even worse than ever, due to the economic crisis. They are people who have had no work experience for years and their stay in prison is on their record. Despite their innocence, almost no interviewer gives them a chance. There is no general information, although among the 21 people that El País Semanalmet, only two have acknowledged receiving million-dollar compensation packages. John Thompson, a man with nervous conversation and laughter, was awarded 14 million dollars for his 18 years in prison. He has yet to receive it. The State of Louisiana is bickering with New Orleans over who will share the bill. In the meantime, John has lost no time at all. He has set up an NGO and has bought a house in the city, where he welcomes all pardoned prisoners who need help, whether or not they were condemned to death.

The man who did receive four-million dollars compensation for 10 years was Ray Krone: he invested it in his farm, and it is not doing so badly for him. At the same time, there are cases like Ron Keine’s. A judge set the price of two years on death row at 5,000 dollars. Or worse still, Juan Meléndez’s. He got a pair of trousers, a t-shirt and 100 dollars from the prison when he was freed after almost two decades behind bars.

IN THE ALABAMA CIRCLE, it is explained, above all for the newcomers, that only 27 of the 35 States that practice capital punishment have compensation laws. But they are incomplete, are not applied in practice, or only refer to cases involving DNA. At a national level, there is a law for federal prisoners that sets compensation at 50,000 dollars for each year of erroneous imprisonment, although it has never been applied, because no federal prisoner has ever been exonerated. Congress is at present debating a national law to cover the cases in each state, which number around 500 including the 139 to emerge from death row. However, the proposal supported at present by only 52 of the 435 members of Congress, is infinitely less generous than the Federal law: it talks about two years of indirect economic help to victims, through an NGO that would decide on a case-by-case basis.

On explaining this, the conference room in the hotel was filled with disapproving comments. How is it possible that in a country like the United States at least 139 innocent people have been condemned to death? Various circumstances repeat themselves, case after case. The police that hide or destroy evidence, bad practice on the part of prosecutors, perjury, inexperienced and low-paid court-appointed lawyers, snitches acting only in their own interests... It’s night-time now, outside the hotel, as John says: “The motives are political. They say that we need safe streets. They place the prosecutors in a situation in which they have to win. The goal of any lawyer is to become a judge. They need to win a high percentage of cases to get there. Some of them win as many as 80%. It is impossible to do it without having done something illegal.”

To cap it all, when the errors are revealed, everybody washes their hands: “Nobody wants to admit to them. Many careers and pensions are at risk,” explains Randy Steidl, who spent almost 18 years locked up in Illinois (12 of them, sentenced to death) and lived through two execution dates, the last, by only six weeks. His freedom came in a surprising way. Law students from the Northwestern University of Chicago reviewed his case as a class assignment. That, “along with the honesty” of a state policemen, proved that Randy and another prisoner were not guilty of the murder of a couple in a small town in 1986.

In 2003, one year before Randy was freed, the then governor of Illinois, George Ryan, chose that university, and certainly not by chance, to announce that he was commuting the death penalty to life imprisonment for 167 prisoners who were at the time on death row in the State corridor. The measure sought to avoid irreparable errors and amounted to an acknowledgement that the death penalty was on the way out in his territory. And the truth is that Illinois, where nobody has been executed since 1999, has a terrifying history with regard to corruption and misunderstandings. Many problems were known about or presaged when Ryan took that decision. One of the most scandalous was Judge Thomas Maloney’s, who fixed at least four trials in exchange for bribes between 1977 and 1990. His judicial career, linked to organized crime, came to an end when an FBI investigation uncovered his conduct. In 1993, he was convicted and spent 12 years in prison. A short time after his release, he died. He was 83 years old.

Perry Cobb, sentenced by Maloney in 1979, describes the judge: “He was white and very racist. Everybody he put on death row or in prison was black, like me.” Statistically, Afro-Americans have a greater probability of being condemned to death: in 2008 they represented 41% of the prisoners on death row, despite being less than 13% among the population of the USA, according to the Census Bureau of that country. Perry will never forget what he lost: “It was devastating for my children. It distanced me from my family. I had a wife, with whom I was deeply in love. It took me a year and a half to convince her, with the help of my father, to divorce me. She was on the point of a nervous breakdown and did not want her to raise our children like that. I asked her to concentrate on them. One of my daughters was raped when she was 11. Where was her dad? I couldn’t help her,” he laments.

One of the four trials that were fixed by Maloney put Nate Fields, also a black man, like Cobb, behind bars for 18 years. But although he was sent to death row in 1986 and the judge was convicted in 1993, Nate’s case was not subject to automatic judicial review and he languished in prison for a further 10 years: “This judge had sent hundreds of people to prison. They knew that they’d have to hold many retrials and they didn’t want to. So they preferred to execute me before reviewing my case.” Nate convinced a judge, in 1998, to set bail at one million dollars for his freedom, while awaiting his final trial. He did not have that much money, but in 2003, another prisoner friend of him paid it and Nate was released. After six years on the street, a judge in Chicago finally declared him innocent last April.

THE POLICE IN ILLINOIS have also been shaken by a lack of scruples. The ex-chief of police in Chicago, Jon G. Burge was removed from his post at the start of the nineties after an internal inquiry discovered that he had been involved in at least 50 cases of torture. Up until now, Burge’s dismissal is all he has paid for his acts. But Ronald Kitchen, at liberty since July 7th, holds onto the idea that the person who ordered him to be beaten up for 39 hours, until he signed a confession to a crime that he never committed, should end up behind bars.

This Afro-American smiles euphorically today and hugs his girlfriend Katina whenever he can. “I’m happy. And each day that goes by I’m a little happier,” he says after his 21 years in prison, 13 of which he was sentenced to death. He tells us in Alabama that on his first day of freedom he hugged his 20-year-old son for the first time and afterwards ate an ice-cream.

In 1988, Ronald was a drug dealer, as he freely admits. Then, a snitch accused him of murdering two women and three children. The man was in prison at the time and subsequently had his sentence reduced. He was the brother-in-law of Ronald’s cousin. Ronald’s sure that it was all a trap to get rid of him. Without any more proof than the word of the informer, he ended up on death row, having gone through torture.

Free after two decades and with imperturbable good humor, he insists that at the moment all he wants is to enjoy each day as it comes. He only backs off from playing basketball. It reminds him of his free time in prison.

A false tip-off was also behind Albert Burrell’s conviction in 1987, this time in the State of Louisiana. This humble, affable man and with the look of a cowboy, tells his incredible story in a tiny voice. After divorcing from his wife, Albert won custody of their five-year-old child, Charles. A couple’s murder in the area where he lived was the perfect opportunity for his ex-wife, who telephoned the sheriff and told him that her ex-husband was the murderer. Having neither proof nor witnesses, based only on a woman’s spiteful lies, the police and the judge believed her version. Or, overburdened by the social pressure to solve the crime, they wanted to believe it. Albert spent the next 13 years on death row in Angola (Louisiana), one of the harshest prisons in the USA, and his ex recovered custody of the child.

Albert, who had lived as an inmate in a psychiatric center since he was 16 because of learning problems, was a perfect target, as he knows neither how to read nor how to write and has minimal cultural resources. It was only the altruistic help of two lawyers from Minneapolis who learnt of his case that got him out of prison. Today he earns a living, at 10 dollars a day, on a farm in Texas. To add to his misfortunes, Albert’s brother ended up marrying his ex-wife, who was never been judged for having falsely accused him. He does not say a word to them, and has no idea of where his son is. He knows that he changed his name and little more. Albert lost everything, but he says, while drinking a beer, that he feels “very lucky.”

The fact is that he is. “There are 139 exonerated prisoners. Only 21 of us are here. The rest: suicides, drug addiction, alcohol... Others do not wish to remember anything. Those that have been on the outside the longest try to help those that have just been released. We say to them: if you have got through your last dollar and you are going to steal... call me. If you are hungry, call me. Before going down the wrong road, call me,” insists Ron Keine, another ex-convict. He thinks that North Americans are not aware that their judicial system has broken down: “It can happen to anyone. But they’re not aware that it’s broken down because they’ve never had to fight against it. They believe they shouldn’t worry because they’ll never commit a crime.”

According to Gallup, a third of all North Americans who support the death penalty think that their country has executed innocent people, but even so they consider this collateral damage, which is worth accepting in the fight against crime. However, in another poll, this time by Harris, 41% of United States citizens reject the idea that the death penalty cuts down on crime. Apart from the risk of a miscarriage of justice, the economic crisis could now be the perfect ally for the abolitionists. Death row is too expensive compared with life-imprisonment, as in the first place the prisoners have a right to all possible appeals: nine proceedings that ratchet up the final bill as much as they prolong the agony for years. Thus, in some sectors of the population the idea of making savings is taking root, although some lawyers see it all very differently, as the system is quite a lucrative business that many would not like to disappear.

THE COLD NUMBERS appear much hotter when given a face, a name and a surname.

In the “exclusive club” of 139 North Americans rescued from the death penalty, the word hope has a particular meaning. “On death row, hope can kill you. Anything good that you expect... if it doesn’t materialize... argh! Today, I face everything as if I was going to go through the worst, but I’m expecting the best. And surprisingly, the best usually happens,” a nervous Greg Wilhoit assures us, who has still not been able to get over the alcoholism to which he succumbed after recovering his freedom.

After five days sharing the hotel, food, drink, and conversations with 21 people who were on the point of dying for crimes that they didn’t commit, we have to say goodbye. Shujaa Graham is an Afro-American who can be overcome by emotion. With tears in his eyes, he thanks us and repeats: “I’m a soldier.” His wife, Phyllis, the white nurse with whom he fell in love in prison, had closed the workshops in Alabama, singing an emotional chorus from the years of slavery in the Deep South.

The words are also apt for the exonerated ex-prisoners.

The group firstly linked their hands, then clapped and sung in unison: “We who believe in freedom cannot rest!” Shujaa gives us a t-shirt with the face of Cameron Todd Willingham, the last known case of an innocent prisoner executed, on 17 February 2004, in Texas. The authorities had offered him life imprisonment, but he rejected it, convinced the truth would come out. The convict’s last words appear on the back of the t-shirt: “I am an innocent man, condemned for a crime that I did not commit. I have been persecuted for 12 years for something that I did not do.” Minutes later, a lethal injection paralyzed his heart. The truth came too late, last summer. Willingham should have been with us in Alabama.

The 5th World Congress against the Death Penalty is taking place in Madrid until June 15.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.