The clan that ruled the roulette wheel

The Pelayo family's almost-infallible gambling method won them over 1.5 million euros Their incredible story is now being brought to the big screen

Gonzalo García-Pelayo's winning racehorse is named Going Wrong, and bets are 12 to 1 just before the race at the tracks in Cheltenham, UK. The 450 euros that he has put down on the jockey in the green-striped shirt is part of a "private investment fund" which relies on tipsters and earns him a 30-percent annual return. Just then, his cellphone vibrates: it's a text from another tipster. In the match between Fernando Verdasco and Juan Martín del Potro, he should bet against the Argentinean tennis player winning more than four games against the Spaniard. García-Pelayo then explains that he is in the process of creating a new formula for tennis bets based on the theory that if the pre-match favorite favorite loses the first set, he or she will win the second. If his studies prove conclusive, he will program it on his computer, under "Favorite loses first set" so it automatically launches.

The race starts at Cheltenham. García-Pelayo leans back on his office chair, watching the screen with the remote in his hand. It's mid-afternoon on a Tuesday in March, and the gambler is dressed in cords and checkered shirt. His white beard and hair are disheveled, his reading glasses hang from his neck. His desk is covered in several layers of dust and papers scribbled with formulas and numbers - their degree of yellowing is a like a scale that reflects the strata of his life as a gambler.

This is more or less the position in which he spends his days at home in Madrid, although he does inch closer to the screen in order to determine the exact placement of his horse (Going Wrong seems to be in third place, maybe second; it's hard to tell on the small screen).

At times he gets up to check the other four computers he has placed in various rooms in his house. They are all buzzing with their own activity, offering players from all over the planet bets that he has programmed. An electronic cry of "Goal!" can be heard every so often from one of them, announcing a new development in the ongoing Debrecen-Kaposvár game in the Hungarian League. The software immediately updates itself, offering 2.6/1 that it will be four-goal match. Soccer is the axis upon which García-Pelayo's private fund rotates. His computers offer 200 bets daily, from which he expects to earn some 15,000 euros a month, part of which will go to the investors and the remainder to a retirement fund. It took him a year to study how and what to program: "a degree in sports betting," he calls it. Though he will be 65 in June, there are a lot of unexplained gaps on his résumé.

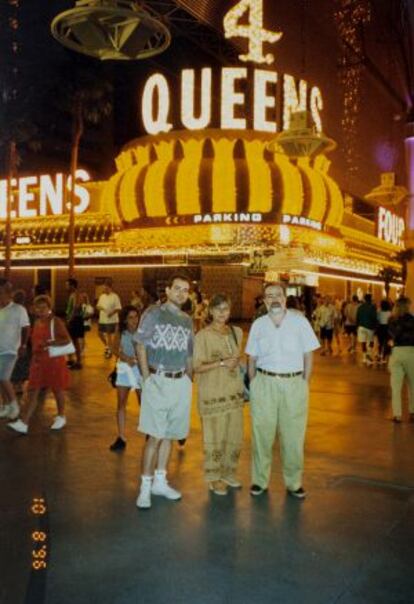

Gonzalo is the patriarch of the Pelayo clan, a family who shot to fame in the 1990s for designing a statistical-based method for winning on the roulette wheel. According to the family's estimates, they won some 250 million pesetas (1.5 million euros) between 1991 and 1995, mainly in the Madrid Gran Casino - their "greatest enemy" but also the "laboratory" in which they tested their system. So Gonzalo and his son Iván wrote in La fabulosa historia de los Pelayo (or, The fabulous history of the Pelayos), published by Plaza y Janés.

Their discovery was accidental. Gonzalo had sent his nephew to the casino to learn the ways of the croupiers. He wanted to study their "ways of dropping" in the hopes of determining a pattern in the path, bounces and final resting place of the ball. His nephew took down numbers and dealers' names; Gonzalo analyzed the data on a program on his computer. That was when he discovered that some numbers come up a lot more often than others, a tendency that had nothing to do with the dealer and everything to do with defects in the manufacture and leveling of the tables. His hypothesis: "If Swiss watches and NASA rockets have imperfections, then so do roulette wheels."

His computers offer 200 bets daily; he expects to earn €15,000 a month

These were the times of the get-rich-quick schemes, of the Seville Expo and the Barcelona Olympics. The patriarch decided to try his luck at roulette following a series of business failures, he recalled recently in an interview along with his children, Iván and Vanessa. He has tried his hand at most everything: from radio announcer to matador manager. In the 1970s, he had a go at the movie industry. His second movie, Vivir en Sevilla (or Living in Seville, 1979) received the following review from critic Fernando Trueba: "Clumsy dialogue and too calculatedly avant-garde."

Next, García-Pelayo opened a nightclub in Seville, where as DJ, he played Pink Floyd and Frank Zappa. He went underground after a judicial order closed the establishment down on rumors that minors were using drugs in its backrooms. He moved onto the recording industry, discovering artists such as Triana and María Jiménez. In total, he left his signature on some 130 albums, including some by Luis Eduardo Aute, Gato Pérez and Joaquín Sabina. The latter singer dedicated a few lines to García-Pelayo in his well-known song, 19 días y 500 noches (or, 19 days and 500 nights), including: "Yesterday, the doorman threw me out of the Torrelodones casino."

García-Pelayo branched out into producing TV programs, and had a few hits, but he shut down his company after he was accused of fleeing to Brazil, he says, and by that point, they were no longer taking his calls in the music world. So he started looking for a new gig, "beyond the limits of luck," as he calls it.

After his first few hypotheses on roulette tendencies, García-Pelayo formed a team led by his son, Iván, a recent philosophy graduate and musician (he composed Africanos en Madrid (or, Africans in Madrid)). There wasn't anybody over 26 years old in the first group. Though the figures and dates are now blurred, as often occurs in legends, after a "few months" recording numbers and working with the data, betting began in earnest in the fall of 1991. According to the book, they won close to "a million pesetas a day" in the first month. They played every day, from 5pm to closing. "A blue-collar job, not at all glamorous, with 12-hour days," says Iván. "And on your feet the whole time," adds his sister, Vanessa.

They are interrupted by the sound of their father's cellphone ringing - the Beatles' Eleanor Rigby is the ring tone, and he comments that he would like to see a movie which portrays his clan like the Liverpool quartet, with "producer Phil Spector hovering in the background." That role is actually played by actor Lluís Homar, the spitting image of García-Pelayo. And the preceding scenes, or a version of them, kick off the The Pelayos by director Eduard Cortés (the movie premieres on April 27). "We are the Pelayos, and we have the opportunity to do something extraordinary: break the bank in a casino," says actor Daniel Brühl (Good Bye, Lenin!) in the role of Iván.

"This is a classic story: the dream of a handful of social pariahs whose rival is big business," enthuses the director, who fell under the family's magnetic spell after living with them for a period.

If Swiss watches and NASA rockets have flaws, then so do roulette wheels"

Though the film mixes fact and fiction, the script accurately reflects the clan's hostility toward the managers of the Torrelodones casino. "Every great feat has a great enemy," say the Pelayos today (and in the book: "We relish our detestation for the casino managers in the way that a boxer finds strength in his hate for his opponent"). The family was involved in long-drawn-out court case against these executives that started when they were kicked out of the establishment in 1992 for committing what the casino termed "gaming irregularities." The battle ended with a Supreme Court sentence in 1994 that recognized the legitimacy of the Pelayos' methods and even praised their "inventiveness."

The bad guy in the movie is a malicious casino manager called La Bestia (The Beast), played by Eduard Fernández. The movie doesn't say which casino he works for, but all of this attention has understandably caused concern (and anticipation) among management at the Madrid casino, who were not consulted by the movie's scriptwriters.

"We don't have anything against anybody," says the casino's communications director, his voice mingling with the sounds of chips falling in the European Room at Torrelodones. "The Pelayos really are not part of our everyday conversations around here. They represent just another story among the more than 18 million visitors we get here. We looked into whether they had some sort of advantage over the other players, and we fixed the imperfections in the tables."

He tiptoes around the subject of the expulsions. He doesn't know what the family's total winnings amounted to. He says they never - "no way" - broke the bank. Jesús Marín, pit boss in the time of Pelayos, and current games director, adds, "They never played a lot of numbers, and they always played the same ones. They usually won, but their story has been exaggerated. It was immediately discovered that the roulette tables had a pattern; so first the wheels were switched from one table to another, then the entire tables were replaced. They played three or four weeks in total."

We have the chance to do something extraordinary: break the bank in a casino"

One former croupier, who prefers to remain anonymous, remembers that the Pelayos' winning streak happen to coincide with a labor dispute between management and staff over an annual 2.6 billion pesetas in tips, complete with full and partial strikes throughout the year. "There was a lot of confusion and some things went unnoticed. That probably was a factor. One of the tables, table 13 or 14, was in bad shape. The wheel hadn't been properly leveled, and they discovered this by watching and taking notes. That is where they had their big wins, about 100 million pesetas. But their method never worked as well in other casinos."

The book mentions other wins in Vienna (14 million pesetas in one night), Amsterdam (almost 13 million) and 40 million in Lloret de Mar, where the movie was filmed. But apart from one old Casio calculator, little physical evidence of this past remains today in the penumbra of Gonzalo's bedroom. After being repeatedly thrown out of the Torrelodones casino, he continued to visit the its roulette tables through his string of "underground" players, which included Luis Mazarrasa, a journalist who later published his story in EL PAÍS. There is something about the Pelayo clan that causes one to suffer a slight case of the Stockholm Syndrome. They welcome every visitor as if he or she may be the beginning of something new; there is a half-carved ham leg in the kitchen, and something about the smell of the house and the bookshelves full of movies and albums activates that part of your brain where memories of childhood are stored.

Beyond this, there is the money. Mazarrasa recalls winning 1.8 million pesetas (just over 10,000 euros) in three days. García-Pelayo's team broke up in 1995, when he set up an illegal poker establishment. That's another story - maybe another movie. At the end of his roulette adventures, García-Pelayo had a stash of over 60 million pesetas. But money doesn't last long in the hands of a gambler and travel lover. "For Easter holidays, I will only have whatever I get out of these bets. I live day to day," he says. It is still Tuesday when his winning horse, Going Wrong, finishes ninth, Verdasco loses more than four games to Del Potro, and the cry of "Goal!" continues to be heard from the other computers.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.